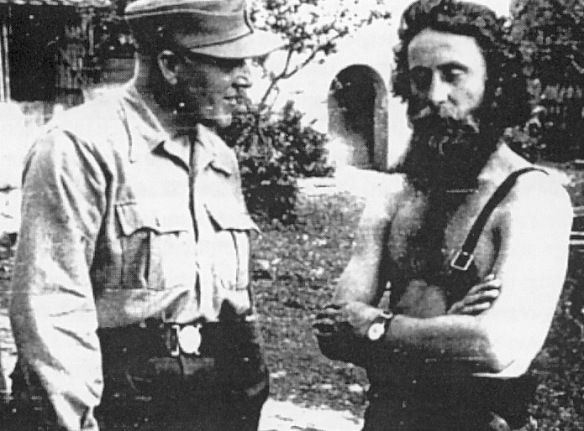

Commander of the 13th SS Division, SS-Standartenführer Desiderius Hampel confers with a Chetnik commander in the summer of 1944.

The SS also recruited thousands of Muslims into its ranks. In fact, Himmler shared Hitler’s favorable attitude toward Muslim soldiers. On 2 March 1943, after a meeting with the Reichsführer-SS, General Edmund Glaise von Horstenau wrote about Himmler’s enthusiasm for the foundation of the Muslim SS division in Bosnia:

Himmler certainly approved of my timidly voiced opinion that in the Bosnian Division the conventional SS cultural policy would be well complemented by the addition of field muftis. Christianity he dismissed simply on account of its softness. The hope for the paradise of Mohammed had at any cost to be fostered with the Bosnians since this guaranteed heroic performance.… Himmler regretted the disintegration of the Austro-Hungarian military border and again and again spoke about the grand Bosnians and their fez.

In the following months Himmler would argue repeatedly in the same vein. As late as March 1945 he would praise “the dauntless Mohammedans” of the Waffen-SS. Like the Wehrmacht officers, he and his subordinates in the SS Head Office also frequently considered the global propagandistic impact of Muslim soldiers in German uniform. Imagining pan-Islamic unity, Gottlob Berger once explained the employment of Muslim units in southeastern Europe as an attempt “to reach out to the Mohammedans of the whole world, since these are 350 million people who are decisive in the struggle with the British Empire.” Similarly, an internal SS report emphasized that the division was to show the “entire Mohammedan world” that the Third Reich was ready to confront the “common enemies of National Socialism and Islam.”

SS recruiters first began to target Muslims in the Balkans, where, in early 1943, the partisan war threatened to divert more and more troops from the German army, already heavily weakened by defeats in the East and in North Africa. The largest Muslim SS unit of the region was formed in Bosnia. From February 1943 on, Himmler recruited thousands of Muslims into the 13th SS Waffen Mountain Division (13. Waffen-Gebirgs-Division der SS), which later was renamed “Handžar” (Handschar). The formation was enthusiastically supported by the leading Muslim autonomists, who, in their memorandum of 1 November 1942, had already suggested the establishment of a volunteer unit under German command. Handžar’s deployment took place under the auspices of the Croatian ethnic German SS-Division “Prinz Eugen” and its choleric commander, SS-Gruppenführer Artur Phleps. A considerable part of the division comprised members of the feared Muslim militia of Major Muhamed Hadžiefendić, which had been created by the Ustaša government in northeastern Bosnia in 1941. In the field, the leading German recruiter of Handžar became Karl von Krempler, who had grown up in Serbia and Turkey and was fluent in Bosnian. Although the majority of the Muslim population appeared to approve of the establishment of this division, fewer of them initially volunteered than had been anticipated. In time, though, recruiters enlisted around 20,000 volunteers. Praised by German propaganda in Croatia as “warriors against Bolshevism and Judaism,” they were to become both a political and a military force in the region.

The Ustaša regime followed these events with the utmost suspicion. Its initial attempts to control the project failed. The SS gave short shrift to Zagreb’s requests to include the word “Ustaša” in the name of the division. In the end, the Germans assured Pavelić that around 15 percent of Handžar would be made up of Catholics and that his regime would be involved in the recruitment process. In reality, Bosnians perceived the division as a “Mohammedan issue,” as Winkler put it. Pavelić’s representative and liaison officer, Alija Šuljak, a Muslim who was notorious for his aggressive Ustaša propaganda, was quickly sidelined by German recruitment officers around Krempler. Many Muslims even deserted the Croatian army to join the new SS formation. Although Pavelić saw his hands tied, his regime missed no opportunity to hinder the establishment of the Muslim division. In April, Phleps complained to Berlin that the Croatian government “uses all possible means to obstruct or at least to delay the formation considerably.” The head of the SS Reich Security Head Office, Ernst Kaltenbrunner, reported similar complaints. In some cases, the Croats came at night for Muslim volunteers who had already been enlisted in the ranks of the SS, forced them out of their beds, and sent them to Croatian army barracks. Furious, Himmler ordered his police commissioner on the spot to clamp down on this practice and to search both Croatian barracks and the concentration camps Nova Gradiška and Jasenovac, declaring that he had “definitive and very precise reports” about young men who had been “transported to concentration camps simply because they have enlisted with us.” The perpetrators, he suggested, should themselves be taken to concentration camps or be executed.

Eager to avoid further Croatian sabotage, the SS moved Handžar to southern France, where the division was trained under the command of First World War veteran SS-Oberführer Karl-Gustav Sauberzweig. The German officials in the Balkans, most notably Horstenau, expressed concern about the transfer at this critical point of the war. Himmler, however, coolly rebuffed any such objections. But before long the concerns of the officers on the ground proved to be well founded. In the summer of 1943, when Tito initiated a major offensive in Bosnia, the relatives of Muslim volunteers were targeted first by the partisans. In France, their sons and husbands soon got wind of the developments at home. They knew that their families were left completely vulnerable and without any viable defense. Shocked by these events, especially since the Germans had promised them employment in their own country to protect their homes, many of the Bosnian volunteers became disillusioned. Discontent rose. In the night of 16–17 September, a group of soldiers rebelled and shot an officer. Although caught off guard, the Germans quickly put down the revolt, with fifteen soldiers killed. Numerous rebels were arrested and publicly executed by firing squads. Berger blamed not the Muslims but the (around 2,800) Catholics of the formation. A bit later Hitler expressed the same opinion, stressing that only the Muslims of the division had been proven trustworthy. Soon Handžar was moved to the Silesian training ground at Neuhammer, where Himmler visited twice and gave his motivational speech. Al-Husayni, too, was sent there. Publishing a photo series of his visit to Neuhammer, the Wiener Illustrierte explained to its readers that the Muslims were to fight in the SS ranks with “fanatic faith in their heart,” knowing “that only on the side of Germany can they sustain their freedom of faith and freedom of life.” Finally, in late February 1944, the Muslims were sent back to the Balkans. “Our Führer, Adolf Hitler, has kept his promise. A new era is dawning. We are coming!,” announced a propaganda leaflet distributed throughout Bosnia. Another one declared, “Now we are here!” to fight “every enemy of the homeland.” Hitler and Himmler had personally approved these pamphlets. Handžar was mostly used for antipartisan operations in northeastern Bosnia and acquired a grim reputation for its brutality and violent excesses. A British liaison officer with Tito’s partisans reported on the division’s atrocities: “It behaves well in Moslem territory, but in Serb populated areas massacres all civil population without mercy or regard for age or sex.” After the war, an officer of Handžar gave a graphic report of crimes committed by members of the division: “One woman was killed and her heart taken out, carried around and then thrown into a ditch.” Hermann Fegelein, Himmler’s liaison officer at Hitler’s headquarters, reported to Hitler on the atrocities of Handžar during a military briefing on 6 April 1944, describing how the Muslim division had spread fear across the Balkans: “They kill them with only the knife. There was a man who was wounded. He had his arm tied up and with the left hand still finished off 17 enemies. There are also cases where they cut out their enemy’s heart.” Hitler was not interested. “I couldn’t care less” (Das ist Wurst), he replied, and carried on with the meeting’s agenda. A few months later, an internal Wehrmacht report noted: “Muslims have done very well, and so they must be extensively supported and strengthened by military and civil agencies.” Berger, too, was impressed, declaring that “fighting against Tito and the Communists thus becomes for the Moslems a holy war.” When Kersten asked him about Handžar’s military performance, he replied: “First class, they are as tough as the best German divisions were at the beginning of the war. They regard their weapons as sacred.… The Moslems cling to their flag with the same passionate courage, the Prophet’s ancient green flag with a white half-moon, stained with the blood of ancient battles, its staff splintered with bullets.”

Soon, however, it became clear that more local help was needed in the Balkans. Desperate for manpower, German recruiters began to target Albanian Muslims. In early 1944 Hitler endorsed the formation of a Muslim division of Albanians, the 21st SS Waffen Mountain Division (21. Waffen-Gebirgsdivision der SS), called “Skanderbeg.” Skanderbeg, which was deployed in Kosovo, in the area between Peć, Priština, and Prizren, was to operate in northern Albania and the borderlands of Montenegro. It consisted of recruits from the local civilian population, prisoners of war, and Albanian soldiers from Handžar. Enlistment of civilians was, as documents in the Albanian Central State Archive show, organized in close cooperation with the institutions of the Albanian puppet state, most importantly the Ministry of Defense. Keitel ordered the release of Albanian prisoners of war of the “Muslim faith” to swell the ranks of the unit. The basis of the new division, however, was formed by the Albanian contingent of Handžar. Himmler expected “great usefulness” from the unit since the Albanians who fought in Handžar had proved to be highly motivated and disciplined. In practice, though, the division suffered from a shortage of equipment and armaments and a lack of German staff to train new recruits. Over the summer and autumn of 1944, only a single battalion had been readied for combat and employed to fight partisans. “Day-in, day-out and night-in, night-out, Skanderbeg units advanced into the mountains to cover the flanks of the retreating troops,” observed a German soldier in Prizren. “They were the horror of the partisans.” Ultimately, the battalion became directly involved in Nazi crimes. In July 1944 the commander of Skanderbeg, August Schmidhuber, reported that his men had taken measures to crack down on “Jews, Communists and intellectual supporters of the Communists.” Between 28 May and 5 July the Albanians had captured “a sum total of 510 Jews, Communists, and supporters of gangs and political suspects.” Skanderbeg was also involved in retributive hangings following acts of sabotage. With the numbers of deaths and desertions rising, the division was shrinking steadily. Equally problematic was the formation of a third Muslim division of the Waffen-SS in the Balkans, the Bosnian 23rd SS Waffen Mountain Division (23. Waffen-Gebirgsdivision der SS), known as “Kama.” Established in June 1944, Kama comprised both Muslim civilians and several units from Handžar. After a series of desertions, the SS was compelled to disband the unit in late October 1944, only five months after its founding.

In the East, the SS was initially cautious. The Security Police and the Security Service of the SS in the Crimea were first to recruit Muslims systematically, using them as auxiliaries. Based on an agreement with the 11th Army, in early 1942 Otto Ohlendorf employed some of the recruited Crimean Muslims in his Einsatzgruppe D. Soon 1,632 Muslim volunteers were fighting in fourteen so-called Tatar self-defense units (Tatarenselbstschutzkompanien) of Einsatzgruppe D, scattered across the Crimean peninsula. An SS report about the volunteers praised the Tatars for being “explicitly opposed to Bolshevism, Jews, and Gypsies.” Ohlendorf’s right-hand man, Willi Seibert, noted that they had “proved their supreme worth” in combat against partisans. Eventually, SS officers developed the idea of founding another Muslim division in the East. Walter Schellenberg, head of the foreign intelligence of the SD, had discussed the deployment of a formation of Turkic and Tatar volunteers as early as 1941 in the Reich Security Head Office but had given up on these plans due to a lack of personnel and resources. In autumn 1943 the idea was revived and discussed by Schellenberg and Berger. On 14 October 1943, Schellenberg sent Berger a memorandum on the formation of a “Mohammedan Legion of the Waffen-SS” composed of Muslims from the Soviet Union. The “political-ideological basis” of this unit was to be “Islam alone,” it stated. Convinced that the division would have a political and military impact throughout the Islamic world, Schellenberg summarized his ultimate “aim” in one sentence: “Formation of Mohammedan units for the increasing revolutionization and winning over of the entire Islamic world.” Thrilled, Berger recommended the plan to Himmler. The deployment of an Eastern Muslim division was a “political matter of the highest significance and importance,” he stressed, by which “another part of the Mohammedan world would be won” for Germany’s war. Its formation would demonstrate “that we are serious about friendship with the Mohammedan world.”

The following month, Himmler began recruiting among Soviet Muslims for an Eastern Muslim SS Division (Ostmuselmanisches SS-Division), the name emphasizing the religious character of the formation. The Wehrmacht agreed to transfer its Turkic battalions 450 and I/94 to the SS, where they were to become the basis of the new division. Andreas Mayer-Mader, who was still in charge of his Muslim unit, now called Turk Battalion 450, and part of the Turkestani Legion, was recruited by the SS to become commander of the new formation. He seemed particularly suitable, as he claimed to be an expert in the Muslim faith and on the verge of converting to Islam. The Eastern Muslim SS Division was never fully employed, however. Mayer-Mader’s command remained limited to the division’s so-called 1st Eastern Muslim SS Regiment (1. Ostmuselmanisches SS-Regiment), which derived from the two Wehrmacht battalions. In early 1944 it contained only 800 men. In spring 1944 Fritz Sauckel, Hitler’s general plenipotentiary for labor deployment, released all of those Turkic and Tatar workers from the Labor Service who were willing to fight in the new Muslim unit. SS enlisters also recruited Muslims from prisoner of war camps. With the help of Josef Terboven, Reich commissar for Norway, the SS even screened the prisoner of war camps across Norway for a few hundred detained Muslims. The High Command of the Wehrmacht, though, was increasingly resistant to SS attempts to recruit from its Muslim legions, seeing the SS more and more as a rival in the East. Mayer-Mader, who faced resistance within his unit, was soon discharged, and later killed in mysterious circumstances. He was succeeded by several officers, among them the sadistic Hauptmann Heinz Billig (March–April) and the Nazi careerist SS-Hauptsturmführer Emil Hermann (April–July).100 The 1st Eastern Muslim SS Regiment first fought partisans in the area around Minsk before being sent to Poland to join the infamous Dirlewanger Regiment in the suppression of the Warsaw uprising—as was a regiment of the Azerbaijani Legion of the Wehrmacht.

Meanwhile, the SS continued to pursue the plan of the Eastern Muslim SS Division—now called the Eastern Turkic SS Corps (Osttürkische Waffenverband der SS). Responsibility for the recruitment of the Eastern Turkic Muslims now fell to Reiner Olzscha of the volunteer section of the SS Head Office. First, the SS needed a new commander, one who was familiar with the Muslim world. A German officer who had served in the Ottoman army during the First World War and a former colonial officer from the Dutch army were suggested. In the early summer of 1944, Berger finally found a suitable man—an officer familiar with “the Eastern Turkic-Islamic world.” Himmler’s new commander of the Eastern Turkic SS Corps was fifty-nine-year-old Wilhelm Hintersatz, better known as Harun al-Rashid Bey, an army officer from Brandenburg who had converted to Islam during the First World War and who had worked with Enver Pasha on the Ottoman general staff. During that time he had also met Otto Liman von Sanders, for whom he felt a deep admiration. The campaign for Islamic mobilization in the Great War had strongly influenced Hintersatz, as it had so many others. After 1918 he had become involved with the former Muslim prisoners of war from the Wünsdorf Camp and had served in Italian intelligence in Abyssinia in the 1930s, claiming in his curriculum vitae that the “trust of the native Mohammedans” had been his best “instrument” there. “The Mohammedans saw in me a fellow believer, who prayed with them without timidity in their mosque,” he boasted. He had “always been ready” to cut the “Achilles’ heel” of Germany’s “most dangerous enemy,” England, which, in his view, was Islam. Married with two children, the qualified engineer was not the archetypical adventurer. He had become involved with Islam and Islamic politics by chance. Playing up his “Islamic connections” and describing his “affiliation with Islam” and the trust he enjoyed among Muslims as his “essential instrument,” he had impressed SS officers. Before his appointment, al-Rashid had worked as a liaison officer of the Reich Security Head Office with the mufti of Jerusalem. Olzscha contacted al-Rashid in May: “I wish to make you a very concrete proposition, which also first and foremost considers the position which distinguishes you as a Mohammedan and former officer.” Indeed, within the SS Head Office, al-Rashid’s appointment was explained with reference to his “close relationships to the Islamic world” and the SS propaganda for the “Turkic-Islamic world.”