Lee instead ordered Longstreet to coordinate a massive assault on the center of the Union line, employing the division of George Pickett and brigades from A.P. Hill’s corps. Longstreet knew this assault had little chance of success. The Union Army was in a position reminiscent of the one Longstreet had taken at Fredericksburg to defeat Burnside’s assault. The Confederates would have to cover almost a mile of open ground and spend time negotiating sturdy fences under fire. The lessons of Fredericksburg and Malvern Hill were lost to Lee on this day. In his memoirs, Longstreet claims to have told Lee that he believed the attack on the Union center would fail:

General, I have been a soldier all my life. I have been with soldiers engaged in fights by couples, by squads, companies, regiments, divisions, and armies, and should know, as well as any one, what soldiers can do. It is my opinion that no fifteen thousand men ever arranged for battle can take that position.

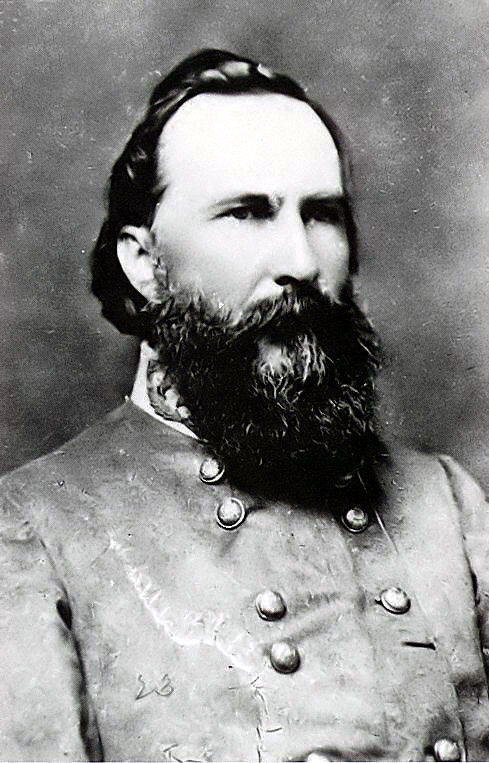

During the artillery barrage that preceded the infantry assault, Longstreet began to agonize over an assault that was going to cost dearly. He attempted to pass the responsibility for launching Pickett’s division to his artillery chief, Col. Edward Porter Alexander. When the time came to actually order Pickett forward, Longstreet could only nod in assent, unable to verbalize the order. The assault, known as Pickett’s Charge, suffered the heavy casualties that Longstreet anticipated. It was the decisive point in the Confederate loss at Gettysburg and Lee ordered a retreat back to Virginia the following day.

Criticism of Longstreet after the war was based not only on his reputed conduct at the Battle of Gettysburg, but also intemperate remarks he made about Robert E. Lee and his strategies, such as:

That he [Lee] was excited and off his balance was evident on the afternoon of the 1st, and he labored under that oppression until enough blood was shed to appease him.

For years after the war Longstreet’s reputation suffered and was blamed for the failed attack even though Lee ordered the advance after Longstreet’s repeated advice to cancel the attack.

Colonel Lindsay Walker, chief of A. P. Hill’s artillery, said: “We [Hill’s corps] were ready at daylight … and waited impatiently for the signal.” Brigadier General Pendleton, in his anomalous position as chief of artillery, was at the southern end of Seminary Ridge at sunrise, tracing positions for guns across from the Round Tops. Even while Longstreet stood with the commanding general’s group on the shaded area of flatland that served as a sort of observation post, Lee was waiting for the return of an engineering officer sent out at sunrise to reconnoiter the southern end of the Federal position.

But the most conspicuous evidence of Longstreet’s procrastination is the fact that, with his van six miles from Seminary Ridge at five o’clock the preceding afternoon, and sharing the common knowledge that Meade was hurrying the concentration of his army, Longstreet took fifteen hours to get his men to the field—and then not deployed for action.

In his explanation, Old Pete attempted to obscure this poor performance by advancing the superiority of his advice which General Lee ignored that morning. According to Longstreet, he urged Lee to try “slipping around” to Meade’s left, southward, and interposing their army in a strong position between Washington and the Federals. The number of latter-day supporters of this alleged plan is amazing in view of some elementary considerations.

There is a scarcity of strong positions between Gettysburg and Washington; there were the hazards of supplying the army while in contact with the enemy; and there was the extreme difficulty of making such a maneuver effective with Ewell’s corps deployed for action three miles to the northeast, the cavalry not up, and the army spread out. One of Longstreet’s own divisions was a day’s march away. With the armies in plain view of each other, there was nothing to prevent Meade from shifting to a strong position when Lee shifted and himself awaiting attack. Finally, Meade, even while rushing his troops to Cemetery Ridge, was taking precautions against such a turning movement, which he knew to be a favorite maneuver of Lee’s.

Unquestionably Lee, in considering the alternatives to his two-pronged attack on the Federals’ flank positions, had considered what Meade would do. Although he was not trying to outthink the Union commander, Lee always projected himself into his opponent’s position. He planned to beat Meade to the obvious move. In the fresh morning light, before the disrupted citizenry were stirring about their farms, he began to evolve the details of attack on the extreme Union left.

This was to come about two miles south of the threatened Federal position on Cemetery Hill, below which Ewell was preparing to renew his halted attack. The rugged boulders of the Round Tops anchored the left end of the line, and Lee reasoned that Meade, in his haste to fortify his right against Ewell, would neglect those natural bastions. Lee visualized a diagonal thrust from the southwest, with his brigades attacking in oblique line to overlap the enemy’s left flank and roll him up to the north of the Round Tops. When the enemy flank was completely turned, the Confederates would push on to the high ground of the ridge and take and hold the plateau. The Federal troops farther north on the ridge would be caught in enfilade and forced to abandon the position.

With threats at the other end of the Union line on Cemetery Hill and Culp’s Hill, and with demonstrations in the center, the maneuver was soundly conceived. Not brilliant nor reflective of Lee at his imaginative best, the operation was within the potential of his troops and contained the elements of success.

Longstreet, in his claims for his own plan, attributed Lee’s rejection of it to a bloodthirstiness that caused him to think only with adrenalin when he was fighting. There is no question that Lee, like all great fighters, was a killer once the battle was joined. That should not be taken as meaning, however, that blood lust inundated his brain when he stared through his field glasses at “those people” gathering on the opposite ridge.

His blood might have been up after the taste of victory the day before, but, according to the enemy’s reports on his movements, Lee was “coolly calculating.” However, several of the officers standing with him while he waited for the reconnaissance report observed his tension. As of eight o’clock Lee believed the southern end of Cemetery Ridge to be unoccupied in the vicinity of the Round Tops, but he needed the report of the engineering officer for confirmation before he could order the execution of his battle plan.

Contrary to general impressions, Lee’s nervousness during this waiting period was unrelated to Longstreet. Although Longstreet’s two divisions were not ready to go in and his artillery was not up, Lee did not know this. Longstreet personally waited on the grassy knoll with the other generals and staff officers, and, within the limits of Lee’s observations, all of his lieutenants were prepared for action and waiting on his command.

Lee’s strain came from the accumulation of responsibility which he bore alone, all focused that morning in the wait for an engineering officer to do the work of the absent cavalry. As usual, he tried to conceal his tension. His face was outwardly composed in what a staff officer called “the quiet-bearing of a powerful yet harmonious nature.” As always, he was extremely neat about his person. His cadet-gray coat was buttoned to his throat, around his trim waist he wore a sword belt without sword, his dark boots were polished, and his light-gray felt hat, of medium-width brim, sat squarely on his head. His nervousness revealed itself in an inability to keep still.

A.P. Hill, partially recovered from his mysterious ailment of the day before, had joined the group, looking very slight among the large men. With Hill came Harry Heth, wearing a bandage around his head, and too shaken from the shell blow to assume command of his division. As the group was increased by arriving generals and their staffs, Lee paced up and down in the shade of a line of trees as if alone. Occasionally he interrupted his pacing to peer through his glasses across the valley where the Union troops were still gathering. Then he sat down on a fallen apple tree and began to study his map.

Although his ridge rolling southward from the seminary was lower than Cemetery Ridge, it was wooded for most of its length, and Lee seemed convinced that approaches to the attacking-point could be found which would conceal the troop movement from the Federals. According to the incomplete details of the map, the land between the two ridges at the southern end would favor his envisioned enveloping movement, once the men were in attacking position.

The Emmitsburg road ran diagonally across the shallow valley between the ridges, beginning within the Union lines. At about a thousand yards south it was still no more than two hundred yards from the crest of Cemetery Ridge. There the fence-lined road bent sharply to the southwest, toward the Confederate position. At the end of its course between the lines, the road passed below the point where Seminary Ridge faded off. In that area Lee had no troops at eight in the morning. But there the Emmitsburg road climbed the crest of a low rise, and Lee had selected this stretch of the road—where it was more than a mile from Cemetery Ridge—as an anchorage for his assault troops.

Around eight o’clock in the morning General McLaws rode up and reported that his troops were up. Lee greeted him and directed his attention to the map.

Pointing to the high part of the Emmitsburg road, Lee said: “General, I wish you to place your division across this road,” and with his finger showed that he wanted the troops placed in a line perpendicular to the road. Then, explaining that he wanted the troops to get there, “if possible, without being seen by the enemy,” he asked the direct question: “Can you do it?”

McLaws replied forthrightly that he knew nothing to prevent him, and added that he would “take a party of skirmishers and go in advance and reconnoiter.”

Lee told him that Captain Johnston had been ordered to reconnoiter the enemy’s country and said: “I expect he is about ready.”

Lee meant that the engineering officer was about to report, but McLaws, thinking Lee meant that Johnston was ready to start, said: “I will go with him.”

Longstreet, who had been pacing near by, turned and said quickly to McLaws: “No, sir, I do not want you to leave your division.”

Lee, in his absorption, apparently paid no attention to this exchange.

Longstreet then stepped up beside the seated commanding general, leaned over him toward the map, and said to McLaws: “I wish your division placed so,” and ran his finger in a line parallel to the road.

Lee raised his head and said quietly: “No, general, I wish it placed just perpendicular to that, or just the opposite.”

Longstreet turned away without answering. McLaws, perceiving that Lee had no further orders, then asked Longstreet for permission to accompany the reconnoitering party. Longstreet flatly forbade it, and to McLaws it “appeared as if he was irritated and annoyed.” McLaws rode off to his troops and made a personal reconnaissance of the woods south of Seminary Ridge in search of a concealed approach to the point of attack.

Some while after he left, Captain Samuel Johnston rode up to Lee’s group with what turned out to be the most fateful misinformation of the Gettysburg campaign. The engineering officer’s reconnaissance report also represented one of the costliest consequences of the cavalry’s absence, and the desperate expedients to which it forced General Lee. In the emergency, Lee placed his reliance on a single staff officer to perform the mission of mounted troops.

At best, Captain Johnston’s information of the Little Round area was incomplete. There were no detailed sketches of the hazardously rough ground at the southern end of the Federal line. Information obtained by an apprehensive individual crawling about on wooded precipices would naturally give an inadequate picture of the obstacles to mass troop movement. Johnston was intent on what he was to survey when he reached the top.

In addition to this incompleteness, the report of the engineering officer who personally reconnoitered the Round Tops was nullified by a stroke of incredibly bad luck. Captain Johnston had scrambled through the thickets to the choppy rock summit of Little Round Top just after the guarding troops of the night had been withdrawn and just before their replacements arrived. He started his risky journey back with the accurately observed information that Cemetery Ridge in the vicinity of the Round Tops was unoccupied by Federal troops.

Those projecting peaks had not yet been occupied, as Samuel Johnston reported to Lee. But the Round Tops were not the objects of Lee’s attack. He aimed inside of them, to the north, where his men could climb the sloping ridge and get in command of the ground before Meade concentrated there. That area of Cemetery Ridge was likewise free of blue soldiers when the engineering officer glanced along the ridge, but only because of a freak accident of timing.

To that area Meade was even then sending the bulk of Sickles’s corps, with artillery support, to extend southward the line that Hancock’s corps was forming in the center. Onto the ridge between the flank at Little Round Top, not on it, and what might be considered the center of his line—a distance of about a mile and three quarters—Meade rushed between 15,000 and 20,000 men by nine o’clock in the morning.

That was the hour when Longstreet’s reserve artillery, temporarily under young Porter Alexander, arrived at the field and at last completed the concentration of the attacking forces—except for the one brigade, Law’s that was hurrying toward Gettysburg from its rear-guard post.

By nine o’clock the time when Lee could attack with advantage had already passed. The numbers and guns of the two armies were becoming equalized on the southern ends of the ridges, and Federal troop units were constantly pouring onto the field while Longstreet’s men still lounged in groups around their stacked arms.

But, due to the report of Captain Johnston which confirmed his own appraisal of the situation, Lee assumed a condition on the Federal flank which no longer existed. He also assumed that Longstreet’s troops were ready to move out at once. After he listened to the engineer officer’s report, Lee nodded slowly, as if he had made the final decision to commit his battle plan to the test.

Then he turned to Longstreet and said quietly: “I think you had better move on.”

This first direct order to Longstreet to move out was given somewhere between eight and nine o’clock. After giving the casual order, the general mounted his iron-gray horse and rode the arc from Seminary Ridge around Gettysburg to Ewell’s headquarters north of Cemetery Hill.

By leaving the field to Longstreet, Lee showed that nothing had happened to cause him anxiety about Longstreet’s performing with his usual dependability. If, in his concentration on Cemetery Ridge, he had noticed Longstreet’s surliness, as others did, Lee ignored it. He certainly did not associate the sullenness with deliberate procrastination, nor did anyone else at the time.

Such was his trust in Longstreet that the commanding general left his command post in the expectation of a coming attack. He personally went to investigate the man who, because of his failure the day before, Lee regarded as the unpredictable corps commander.