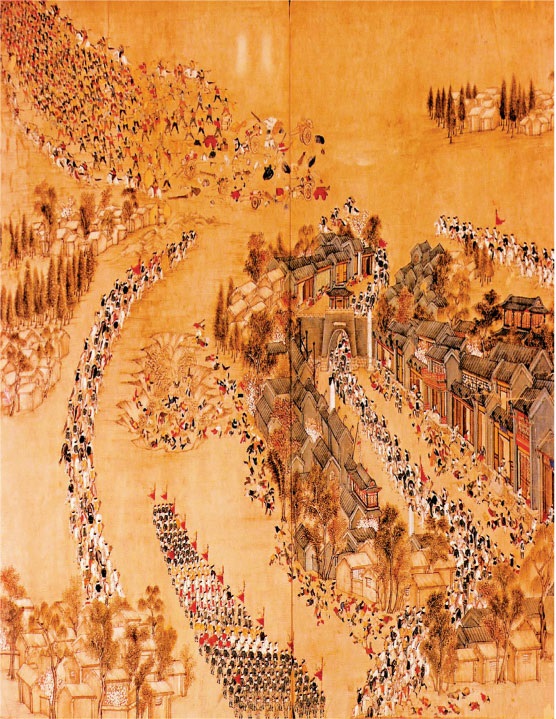

The Taiping forces’ victory over the Qing army in capturing Nanjing is depicted here. The Taiping soldiers, were relentless in training and became fierce fighters. Harvard Yenching Library.

This civil war in mid—nineteenth century china killed more people than any other war in history except world war ii and inspired Mao Zedong’s rebellion a century later.

By the 1830s, the Qing Dynasty had been ruling China for 200 years, since the Manchu conquest of the country in the seventeenth century. The Imperial Court in Beijing was sophisticated and cultivated, the tentacles of its massive bureaucracy spreading out over the countryside, but most Chinese peasants and workers lived in abject poverty. After China’s humiliating defeat by Great Britain in the First Opium War in 1842, even these downtrodden people began to see the Qing rulers as corrupt and weak. When the Yellow and Yangtze rivers overflowed their banks in the 1840s, causing widespread flooding and years of starvation, the country was ripe for rebellion.

The source of the Taiping Rebellion was a highly unlikely one—a deluded failed clerk named Hong Xiuquan. Born a Hakka outsider in the southern Chinese province of Guangdong, Hong failed his civil service exam twice. Perhaps unhinged by this humiliation and influenced by the Christian missionaries who were then preaching in the country, Hong developed the delusion that he was the second son of God, Jesus Christ’s younger brother—his Chinese son. In 1844, expelled by the Confucian authorities of his village, Hong set off to preach that the word of his Taiping Tianguo, or “Heavenly Kingdom of Great Peace.”

As Hong wandered his poor and mountainous province, his message became more political. He had been sent by God to destroy the “demon devils” who ruled China, as well as to create a new way of life, a “Human Fellowship” in which men and women would be equal, and wealth would be shared.

Peasants gradually began to flock to Hong, and by 1850 he had gathered an army of 40,000 near Thistle Mountain in Guangxi Province. Finally alarmed, the Qing rulers sent an army to attack Hong there, but his highly trained and regimented cadre beat them handily in January 1851. After this victory, more peasants joined Hong until his army was hundreds of thousands strong.

Marching down from the Guangxi mountains, Hong and his men swept northeast through the Yangtze River Valley with the city of Nanjing and the port of Shanghai as their targets. They defeated Qing forces at Yong’an and Quanzhou and finally captured Nanjing with an army 500,000 strong in March 1853. Renaming Nanjing his “Heavenly Capital,” Hong now recruited a standing army of more than 1,000,000 men and women.

The Taipings held Nanjing for eleven years, but were unable to capitalize on their victory, mainly because of Hong Xiuquan’s increasing mysticism, licentiousness, and paranoia. As Taiping and Qing forces fought a series of fierce battles over central China, disease and starvation swept the country, causing untold suffering. After failing in a bid to seize Shanghai, the Taiping forces were driven back, thanks in part to the efforts of Charles “Chinese” Gordon, the charismatic British commander of the so-called “Ever-Victorious Army,” who used modern tactics and massed firepower to defeat the Taipings in battle after battle. In May 1864, the Taipings were besieged in their capital city of Nanjing by Imperial troops. Hong Xiuquan died of illness (or possibly suicide) on June 1 and the city fell a month later.

The Qing Dynasty was saved, but it was fatefully weakened. Compromised by the aid it had enlisted from foreign governments, it would fall for good in 1911. In the meantime, an estimated 20 to 40 million people died, making the Taiping Rebellion the most costly war in world history, with the exception of World War II. And within Hong’s madness lay the seeds that would become Mao Zedong’s successful revolution of the mid-twentieth century.

The Siege of Nanjing: October 1863—July 1864

Slowly but surely, the Taiping forces were being driven back. General Li Xiucheng, commander of the rebel army that had tried and failed to take Shanghai in 1862, saw the net inexorably closing around the Heavenly Capital of Nanjing as 80,000 Qing troops, backed by foreign mercenaries and transported by shallow draft steamships owned by the French and British, took Taiping town after town, always promising mercy if the Taipings surrendered—and then slaughtering them—men, women, and children—in orgies of stabbing, shooting, and beheading.

The Qing commander, General Zeng Guoquan, was the ninth brother of Qing strategist Zeng Guofan, who had planned this attack on the vital city of Nanjing and was known with terror in the Taiping army as “General Number 9.” A squat, scarred man, he gave no quarter and expected none. In October, his troops finally appeared and began to form a perimeter around Nanjing. They built a moat 10 miles (16 km) long around its southern perimeter, beginning at the Yangtze River, effectively forcing any relief for the city to come from a direction interdicted by massive amounts of Qing troops.

In mid-December, Zeng sent his men in their first assault against Nanjing’s massive walls. They tunneled under them, filled the tunnels with gunpowder, and blew it up, causing sections of wall to crumble. But Taiping forces, fighting valiantly, pushed the Qings back and repaired the damage.

At this point, Li Xiucheng screwed up his courage and went to see Hong Xiuquan, Heavenly Ruler, to tell him some bad news.

“Why Should I Fear the Demon Zeng?”

Men had been beheaded merely for sneezing in this man’s presence, and Li was nervous as he entered the Heavenly Palace, guarded by a cadre of foreign mercenaries, and found Hong surrounded by concubines, a pale, dangerous wraith of a man.

Bowing before Hong, Li told him that their only hope for survival was to flee. “The supply routes are cut and the gates are blocked,” he told Hong, who listened impassively. “The morale of the people is not steady. The capital cannot be defended. We should give up the city and go elsewhere.”

Hong stared at him and gave a chilling answer: “I have received the sacred command of God, the sacred command of the Heavenly Brother Jesus, to come down into the world to become the only true Sovereign of the myriad countries under Heaven… Why should I fear the demon Zeng?”

Li still believed that Hong was, in fact, the son of God, but he knew that this answer sealed his fate and the fate of the thousands of men, women, and children within the city’s walls. Hong was out of touch with reality, unfit to command an army, and had been for some time. When the city had been captured and renamed the Heavenly Capital some eleven years before, Hong had been at the peak of his powers and had entered Nanjing in triumph, wearing yellow robes and yellow shoes, the Chinese imperial colors. But since then, Hong had steadily deteriorated.

While Hong’s armies fought fruitless battles against Qing forces—battles that sapped strength and morale without achieving clear goals—he remained in Nanjing. Although issuing puritanical edicts to his people, he spent most of his time with his eighty-eight-concubine harem, within a palace protected by Irish and British mercenaries, who were a status symbol for Hong. Hong devoted a great deal of time to mystical poetry and writing down directions for the 2,000 women devoted to cleaning the palace, cooking for him, and bathing and dressing him.

It was no wonder that the reality of the situation outside the walls of Nanjing—what one historian has called “the bloody horror” of raging civil war—made no impact on the Son of Heaven.

Fierce Underground Fighting.

As 1864 began, Li Xiucheng attempted to stockpile what grain he could, sortiing outside the city walls to try to capture supplies, but with little luck. By February, the last grain supplies outside the city were captured by Zeng’s troops, making the town reliant upon only the rapidly dwindling rice in the granaries inside Nanjing. The corruption of Hong’s relatives, whom he placed in a position of power, and who demanded large bribes for grain, caused starvation among the city’s ordinary people beginning in early spring.

Well and truly trapped, General Li Xiucheng watched as the Qings captured every hill, circumvallated the city with a twin line of trenches and breastworks 300 yards (275 m) apart, and placed small forts every quarter to a half a mile (400 to 800 m), 120 in all, each manned by a Qing garrison. As people begin to starve, the Qings sent word to the city that anyone who deserted to the Qing side would be fed and treated well. People risked death to slip out of Nanjing, but when they got to Qing lines, many were executed. According to Charles Gordon, a British observer to the siege now that he had disbanded his Ever-Victorious Army, the escaping women were put in stockades where “the country people… take as wives any who so desired.”

The Qings began to build their mines, tunneling ever closer to the city walls, while Taiping forces dug countertunnels. A savage underground war broke out in the flatland near the city’s walls, with Taiping forces breaking into enemy tunnels and either filling them with water or human waste or fighting hand-to-hand battles, sword and spears flashing in dark caves and recesses. One Qing tactic was to let the Taipings into their tunnels, then blow in noxious smoke with bellows, causing the rebels to die gasping and choking.

Manna

By the spring of 1864, the Qing forces had moved their breastworks to within 100 yards (91 m) of the city. The defenders, low on ammunition, could do little about this but watch. Li finally went to see Hong again, telling him: “There is no food in the whole city, and many men and women are dying. I request a directive as to what should be done to put the people’s mind at ease.”

Hong, still surrounded by his women and his writing instruments, but in yellow robes that had become dirty and tattered, answered him as loftily as he had before. Taking his cue from the biblical book of Exodus, in which God provided food from heaven for the escaping Israelites, he told Li Xiucheng: “Everyone in the city should eat manna. That will keep them alive.”

Then he ordered: “Bring some here and after preparing it I shall partake of some first.”

There was dead silence in the room. Li and Hong’s women and courtiers could not begin to respond to such a strange order. Impatiently, Hong got down off his throne and went into the palace’s central courtyard, where he collected weeds, lumped them into a ball, then handed them to Li, telling him: “Everyone should eat accordingly and everyone will have enough to eat.”

As Li stared at him, the Son of Heaven put a small tangle of weeds into his mouth and began to chew them.

Over the next month, as the battles under and outside the city’s walls became fiercer and fiercer, Hong, on his diet of weeds, grew weaker and weaker. Some historians have suggested that the weeds were poisonous, others that he was simply starving to death, still others that he may have committed suicide. In any event, the Son of Heaven died on June 1, a day after the palace issued a decree to the haggard and starving population of Nanjing that Hong had decided to visit heaven and request of God and Jesus that they send an heavenly army down to smite the forces of General Number 9.

Li watched as Hong was buried on the palace grounds, without a coffin. After all, because he was coming back soon, why would he need one?

“Because I Did Not Understand”

At exactly noon on July 19, Zeng Guoquan gave a signal, and a huge explosion toppled a massive section of walls along the eastern side of Nanjing. Fire and smoke belched into the air as Qing forces poured into the breach. The Taipings could stop them only briefly, then turned and ran.

The battle was no longer a battle, but a slaughter. The Qings rampaged through the city, raping and murdering, while members of Hong’s family sought ways to escape. Usually, burdened down by the loot they had stolen from treasuries, they were caught and executed. Hong’s son and heir, the Young Monarch, managed to make his way out of the city disguised as a Qing soldier, but he was caught in the following weeks and executed.

But aside from Hong’s corrupt family, none of the Taipings left in the city surrendered. A slaughter of epic proportions took place, with Qing forces killing an estimated 80,000 to 100,000 men, women, and children while General Number 9 and his officers cantered their horses through streets literally flowing with blood. Although Taiping armies existed outside the city, the back of the rebellion was broken, and the war was soon to be over.

And what of General Li? After fighting all day, he found his way to a hilltop palace within Nanjing where he fell asleep. He was robbed during the night. The next morning, a Qing patrol captured him, and he was taken to Qing headquarters, where he gave his confession, which included recounting his conversations with the Son of Heaven. He told his captors that, with Hong gone, the Taiping rebellion was over. He begged them fruitlessly for mercy, not for himself, but for the many whose screams still echoed through the city. Then, as if awakening from a nightmare into a newer, darker nightmare, he mused as to why he never tried to stop Hong: “It is really because I did not understand. If I had understood….”

His sentence trailed off, and his confession ended there. That night, he was taken to a small courtyard in the Son of Heaven’s former palace and beheaded.