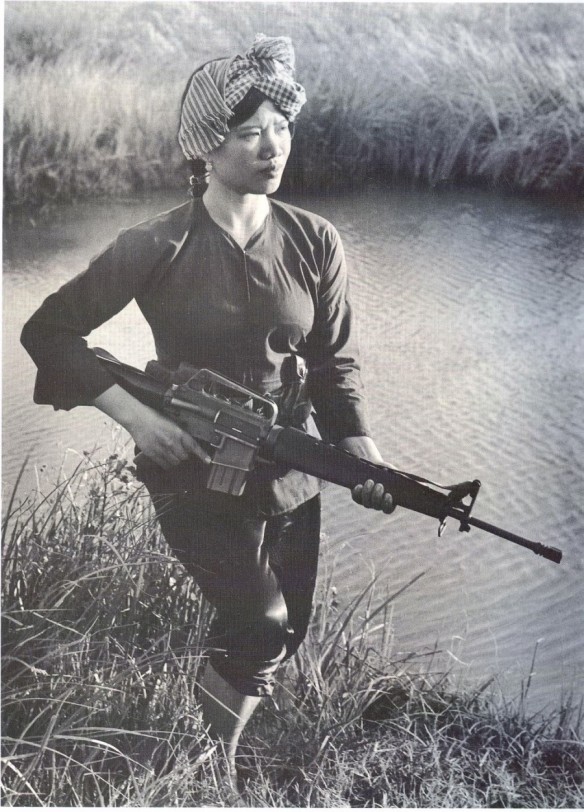

“When war comes, even women have to fight.” This ancient saying of the Vietnamese took on a new relevance in the thirty years that followed the end of World War II, during which the Vietnamese rid themselves of two more foreign interlopers, first the French and then the Americans.

By the summer of 1941, the French colony of Indochina had fallen under the effective control of the Japanese. In December 1944, the Vietnamese guerrilla commander Vo Nguyen Giap organized a group of thirty-five Viet Minh (Communist) guerrillas, of whom five were women. The women were particularly useful in explaining the party line to Vietnamese villagers, who were impressed by their skill in handling firearms.

In 1945, as the war came to a close, Vietnamese women seized Japanese food depots to stave off starvation, and in August and September they joined Ho Chi Minh, leader of the Viet Minh, in the seizure of power in Hanoi, in northern Vietnam. However, the French returned after the Japanese surrender and in 1946 reoccupied Hanoi, the prelude to an eight-year war.

At the outset, Ho Chi Minh’s military commander, Vo Nguyen Giap, suffered a string of defeats before a vital victory at Dien Bien Phu, which led to the surrender of ten thousand French troops in May 1954. During the fifty-five-day siege, short and slight minority tribeswomen played a vital role, hauling heavy equipment, bicycles, artillery components, food, weapons, and ammunition on their backs to supply Giap’s forces, and evacuating the Viet Minh wounded to the rear.

In July 1954, Vietnam was partitioned into the Communist North and US-backed South, as the United States sought to stem Communist expansion in Southeast Asia. Approximately one million women had participated in the anti-French resistance, an experience that foreshadowed the twenty-year war for a reunited Vietnam. From its formation in 1961, women were active in the Communist National Front for the Liberation of Vietnam (NLF).

In 1965, US President Lyndon Johnson decided to commit combat troops to the war. For the North Vietnamese leadership, the struggle against the South and the Americans was seen as both military and political, including recruitment, the maintenance of morale, and the simultaneous undermining of the morale of the South Vietnamese forces and government. For these tasks, women were considered ideal, not least because by 1965 the NLF suffered a severe manpower shortage.

The Women’s Liberation Organization, an arm of the NLF, also had a vital auxiliary military role to play, liaising between villages in the South and NLF units in the jungle, performing intelligence work, providing food and clothing for NLF fighters, concealing them from the enemy, and nursing the sick and wounded. They were also tasked with staging “face-to-face” confrontations with US and South Vietnamese troops, the aim being to harass them at every turn.

Women were also responsible for placing propaganda leaflets for the enemy to find, and Nguyen Thi Dinh, who eventually became deputy commander of the armed forces of the NLF, launched her career in this way. These activities enabled some women to play a significant part in the NLF’s political and administrative cadres. Ho Chi Minh honored them with the name “long-haired warriors.”

Women mainly worked in support formations, carrying huge quantities of rice into the jungle to supply NLF units and returning with wounded fighters, often traversing the so-called Ho Chi Minh Trail, the infiltration route running through Laos to South Vietnam. The young women often had to negotiate the trail carrying burdens greater than their body weight, while suffering from malaria.

By the end of 1967, the numbers of women involved in NLF support and combat operations had risen steeply and they were a constant presence in the resistance to the Americans and their South Vietnamese allies, a factor that was badly underestimated by the US commander, General William Westmoreland, and his staff. While many of them did not bear weapons and few fought full-time, this did not prevent women from being imprisoned, tortured, and killed in Operation Phoenix, the CIA-sponsored attempt to eliminate the NLF.

Women also played a part in the 1968 Tet offensive, which, although a military catastrophe for the NLF, fatally undermined the claims made by the United States that it was making progress in the war. One of the combatant women in Saigon was Hoang Thi Khanh, who had been part of a sapper unit that liaised with NLF guerrillas in the surrounding countryside and smuggled arms into the city. In the buildup to the offensive, she had guided guerrillas—many of them women—into Saigon and coordinated them once the fighting started. After her unit had been roughly handled by South Vietnamese troops (ARVN), she organized a counterattack. She survived until November 1969, when she was captured by the ARVN.

Other women who took up arms during the Tet offensive included two sisters, Thieu Thi Tam and Thieu Thi Tao, who unsuccessfully tried to blow up the police headquarters in Saigon. They were captured, interrogated, tortured, and sent to the prison at Con Dao, notorious for its cramped “tiger cages,” whose open ceilings enabled the jailers to drench the inmates with lime.

Fifteen miles west of Saigon lay the area of Cu Chi, which boasted a vast network of tunnels providing shelter for NLF fighters and containing underground hospitals and assembly points for major operations. The women of Cu Chi had helped to excavate the tunnels, claustrophobic work undertaken in the most dangerous and unhealthy conditions. Cu Chi also boasted a female fighting formation, C3 Company, which had been formed in 1965. All its members were trained in the use of small arms and grenades, the wiring and detonation of mines, and assassination. However, they were discouraged from taking on Americans in close-quarter combat because of their small stature.

The war also subjected the people of North Vietnam to a long strategic bombing campaign, undertaken from 1964 by fighter-bombers of the US Air Force, Navy, and Marine Corps. From the outset, female militias were raised for the defense of North Vietnam, guarding roads and bridges, engaging South Vietnamese Rangers around the 17th Parallel dividing the North and South, and serving in antiaircraft batteries, both artillery and surface-to-air missiles (SAMs). By the time US B-52s launched their own strategic bombing campaign, Linebacker II, in December 1972, Hanoi was the most heavily defended target in the world.

By then all young women in North Vietnam had long been required to join the local militias and self-defense units, making up some 40 percent of the total personnel. They also moved into roles that very few women had filled before 1965. Approximately 32 percent of North Vietnam’s skilled and scientific workers were women. Women replaced men in the health sector and provided some 70 percent of the North’s workforce, toiling in factories, fields, and offices. They taught in universities and worked for the government.

In the rural areas, women cared for and educated the children evacuated from urban centers to save them from the bombing. They worked on the Ho Chi Minh Trail, wielding picks and shovels, heaving baskets of soil, and filling bomb craters by day so that trucks could roll by night. Rural women were already inured to hard work. Now they had to learn new skills to operate heavy machinery and raise rice yields and a range of new crops.

The women defending North Vietnam provided ideal subjects for war photographers. Perhaps the most famous image of the home front in the North was that of a minute young peasant girl, Nguyen Thi Kim Lai, the seventeen-year-old commander of a female militia unit, escorting a US airman who had been shot down in December 1972 during Linebacker II. The sight of the hulking American, his head bowed and hands tied, dwarfing the tiny, alert woman wielding an elderly rifle, provides a metaphor for the humbling of the United States in Vietnam. In 1985 the airman in the photograph, William Robinson, returned to Vietnam to meet Nguyen Thi Kim Lai and to ask for her forgiveness, which she readily gave.

Reference: Sandra C. Taylor, Vietnamese Women at War: Fighting for Ho Chi Minh and the Revolution, 1999.