Battle of Hastenbeck. Reconstruction based on the maps of “Großer Gerneralstab, Kriegsgeschichtliche Abteilung II, Der Siebenjährige Krieg 1756-1763”, vol. V; and “Camps topographiques de la Campagne de 1757 en Westphalie ect., par le Sr. Du Bois”, Le Hague, 1760. – Christian Rogge

Striking south out of Saxony into the Austrian province of Bohemia, Frederick of Prussia won a smashing victory over the Austrian army outside Prague, then trapped more than forty thousand Austrian soldiers in the city and laid it under siege in early May 1757. While waiting for them to submit or starve, however, he found his own supply lines cut by a second Austrian force, commanded by Field Marshal Leopold, Count von Daun. With his options suddenly limited to attack or withdrawal, Frederick again took the offensive and marched an army of more than thirty thousand Prussians against Daun’s fortified camp near Kolín. He lost nearly half of them in a great battle during which fully two-thirds of the infantrymen in his army were killed, wounded, or captured: as Frederick would explain to George II, he was compelled to break off his attacks “for lack of combatants.” Defeat left him with no choice but to raise the siege of Prague and withdraw his army from Bohemia. This crisis in the continental war furnished “dreadful auspices . . . [to] begin with,” but Pitt and Newcastle would soon hear worse. Even as Frederick was retreating from Bohemia, the French were moving against his territories in East Friesland, their allies the Swedes were sending thousands of troops against Pomerania, and the Russians were poised to invade East Prussia.

By the middle of July, the Prussian king was bombarding Pitt with pleas to do something, anything, to relieve his distress: at the very least, he might dispatch British troops to Hanover, to replace the Prussian contingents in the Hanoverian army and free them to defend their own country. Yet that, for reasons soon to become apparent, was the least possible of all solutions to Frederick’s problems.

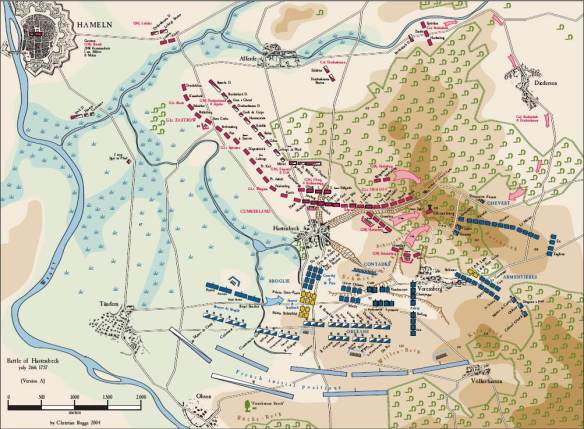

Although Britain had sent no troops to defend Hanover, the king had dispatched his son, William Augustus, the duke of Cumberland, to lead the electorate’s armies. Cumberland had not been a bad choice. At age thirty-six, he had already gained considerable experience as an army administrator, had seen battle during the previous war, and had the physical courage to lead men in combat—but the terms of his appointment were ambiguous, and he had come to the Continent with “orders that read more like the minutes of a cabinet meeting than an operational document.” In mid-July, as Frederick pelted Pitt with demands for help, a large French force crossed the Weser. Frederick helpfully suggested that Cumberland attack immediately, despite the fact that the French outnumbered his army by approximately two to one. Cumberland, declining the king’s advice, took up defensive positions at a village called Hasten-beck, not far from the Weser, and waited. The French attacked on July 25, dislodged Cumberland’s army, and forced it to retreat northward, toward the mouth of the Elbe.

Cumberland hoped that the British navy could bring him the reinforcements and supplies he needed to counterattack; but the French outflanked him and cut him off from the river, then sat back and waited for him to make the next move.

Cornered and impotent, the duke now came under intense pressure from Hanover’s ministers of state to make a peace that would save their country from being overrun. In early August it only remained unclear when, not if, Cumberland would negotiate. His father privately instructed him if necessary to make a separate peace for Hanover, and there was no doubt that his commission, muddled as it was, empowered him to negotiate any settlement he thought prudent. The longer he delayed in negotiating, however, the less credible his defeated army grew as a threat, and the less likely he would be to obtain favorable terms from the French. As August wore on, the ministry’s hopes for retrieving the military situation on the Continent waned, the king’s anxieties for preserving Hanover’s sovereignty mounted, and Frederick’s concerns for the defense of Prussia grew more desperate. Everything now focused on Cumberland’s ability to extricate himself from a situation that grew more dismal by the day.

Only a few hopeful developments relieved the grimness of the Pitt-Newcastle ministry’s first days. On July 8 news arrived from India that military affairs in that distant quarter, at least, were improving. Fragmentary reports had been coming in since Christmas that the army of the nawab of Bengal had attacked the British East India Company post of Fort William at Calcutta the previous June, with disastrous results for its garrison. Now word arrived that at New Year’s, Lieutenant Colonel Robert Clive—deputy governor of Fort St. David, the East India Company factory at Madras—had retaken Calcutta from the nawab’s army. With the receipt of dispatches informing him that Britain and France had declared war, Clive had gone on to attack Fort d’Orléans, the French Compagnie des Indes factory at Chandernagore, and had forced its surrender on March 23.

Because months of travel were necessary to relay information from India, no one in England yet knew that on June 23 the indefatigable Clive had gained a decisive victory over the nawab at the Battle of Plassey and seized control of all Bengal. That knowledge would surely have cheered Pitt, but in early July he remained wary. “This cordial,” he wrote to a political ally of the news that Calcutta had been regained and Chandernagore taken, “such as it is, has not the power to quiet my mind one minute till we hear Lord Loudoun is safe at Halifax” and ready to launch an assault on Louisbourg. To his great relief, the dispatches that arrived from America on August 6 brought the news he longed to hear. Loudoun had arrived in Nova Scotia at the beginning of July and his preparations for the amphibious attack on the great Cape Breton fortress were proceeding apace. “I am infinitely happy to think of the joy this news will give [in the household of the Prince of Wales],” Pitt wrote to the prince’s tutor, the earl of Bute. Unfortunately for Pitt’s peace of mind, this would prove the last piece of encouraging news from America for a long, long time.