“Our crews were between 18 and 24, and inexperienced,” said Werner Kortenhaus, a tank wireless operator of 21 Panzer Division, the key formation defending Caen, near enough to the beaches to intervene decisively on D-Day. “My own 4th Company was the only one up to its full strength of 17 Mark IVs; but we had had little time for practice with them and had done only one or two range-shoots. We were expecting invasion, of course, but had no idea where it would come, when, or in what strength. In fact, we knew nothing except our daily duties. These became more and more exhausting. First, single-sentries. Then double-sentries were added. Then the double-sentries were forbidden to talk to each other while on duty. This continuous tightening up convinced us that something was afoot. We cut down trees to give a field of fire, then had to drive the trunks into the ground as an anti-glider precaution, the so-called ‘Rommel Asparagus’. This job was not much appreciated, as we doubted its effectiveness. Finally, we had to leave our billets and sleep in tents beside our tanks, and then we knew that invasion was imminent. We did realise that the battle would be decisive, but as we thought the war lost anyway, there seemed to be no worthwhile goal.”

On 29 May, Field Marshal Rommel was in the Caen area inspecting units of 21 Panzer Division with their commander, Generalmajor Edgar Feuchtinger. Among the locations was the anti-tank gun ‘hedgehog’ at Cairon, halfway to the coast, admirably positioned, as it turned out, to block the advance of 3 Canadian Infantry Division and its supporting armour in eight days’ time. But the transport was a hotch-potch of mostly French vehicles, the 75 mm SP (self-propelled) guns being mounted on the chassis of a Renault half-track; the defensive minefields were fenced off with barbed wire, and labelled; and French civilians were still moving around freely, able to inspect all the German preparations. “We found out, when the invasion started, that the enemy knew more about our defences than we did ourselves,” commented Leutnant Hans Höller, who commanded a Section of three guns at Cairon. “I took some photographs of Rommel inspecting our division, and the general report was that he was not satisfied with the fortifications in the coastal area. Certainly, the pictures show him looking as black as thunder; but like many German generals at that time, he was balanced on the razor’s edge of revolt, forced to think two ways—how to hold off the Allied invasion and, simultaneously, how to overthrow the Führer and the Party. This was not merely suspected by the Führer but known by that time even to the Allied generals waiting across the Channel.3 The last-minute leakage of the ‘Morgenthau Plan’, following on the demand for ‘Unconditional Surrender’, made the latter task, which might have ended the war in 1944, far more dangerous and difficult; indeed, for Rommel, as for many others, it was to prove fatal.

Night of 5/6 June 1944

At Epanay, south of Caen, where Werner Kortenhaus was stationed with 4 Company of Panzer Regiment 22, 21 Panzer Division, a special patrol was sent out to check the whole neighbourhood; but by midnight, everyone was awake anyway, because of the exceptionally heavy air activity. At 0100 hours, the official alarm came through and they prepared their tanks for action; but no further orders arrived and they made no move for another five hours. At Cairon, between Caen and the coast, where Leutnant Höller was stationed with the anti-tank guns of 8 Company, Panzer Grenadier Regiment 192, 21 Panzer Division, the alert was received at about 0200. By that time, said Höller, “the earth was shaking with the tremors of the bomb carpet and the sky above Caen was glowing red. The French people in my billet had been extremely kind, and with the ground trembling under us, they pressed food and drink on me and said goodbye. We soon loaded up the vehicles and took the road for Bénouville. I cannot remember who gave this order, as in the beginning all the leaders were very uncertain; but probably it was Oberstleutnant Rauch, the Regimental commander, whose whim was always to react immediately to any change in the situation.” Bénouville covered the two vital bridges over the twin water barriers of the Orne and the Caen Canal; and was the objective of 5 Parachute Brigade, 6 Airborne Division.

What the paratroops had to fear was immediate armoured counter-attack, before the seaborne troops could arrive with their heavier weapons. The blowing of the Dives bridges would prevent any immediate assault from the west, but there were very few anti-tank guns to bar the road which led south to Caen, behind which the tanks of 21 Panzer Division were waiting. What that division did during the next few hours would be vital, probably decisive, because they were near enough to intervene almost immediately. That part of the division which was at Cairon, nearest to the airborne landings, was ordered to move at once, as we have seen, and by 0330 was in action against 5 Parachute Brigade at Bénouville, overlooking the Orne and Canal bridges. They consisted of infantry and anti-tank guns; the tanks were south of Caen. Five hours after having been alerted, the tanks were still waiting, with the precious hours of darkness slipping by. At 0600 hours came the order to move, and they roared forward to the main Caen-Falaise road; and stopped again, strung out at intervals under trees. To the north, the sky was red; Caen was burning. Some drivers kept their engines running, because they expected an immediate advance, but nothing happened for another two hours, except that German vehicles from other units began to move past them towards the coast and a stream of refugees from Caen began to appear, going inland. Then, at 0800, their forward movement almost precisely synchronised with the arrival of the British and Canadians on the beaches the other side of Caen, they received the order: “March!”

Military operations are an art, not a science, because they are conducted without full knowledge of the facts, most decisions being made on partial evidence only. And because ruses and feints are to be expected, part of that partial evidence may be false, designed deliberately to mislead. In commerce, it has been said, the business man who manages to make six correct decisions out of ten, automatically becomes a millionaire; Rommel had become a Field Marshal because he had what he called a ‘finger-tip feeling’ for the real situation, which enabled him to guess right, more often than not. In Paris, it could be deduced that the landing of parachutists on a large scale must indicate a seaborne follow-up, to prevent the sacrifice of the lightly-armed airborne troops; but whether this was to be another and greater Dieppe Raid, timed to put the defenders off balance, or the invasion itself, could not then be known. The two nearest available divisions of the strategic armoured reserve, held back as a counter-offensive force, were Gruppenführer2 Witt’s 12 S.S. Panzer Grenadier Division, composed of volunteers from the Hitler Youth, stationed 30 miles south of Lisieux, and Generalmajor Fritz Bayerlein’s formidably-equipped Panzer Lehr Division, 75 miles south-west of Paris. On Hitler’s orders only, could they be moved. Nevertheless, without asking permission, Field Marshal von Rundstedt instructed both to advance on Caen; but at 0600 hours had this order cancelled angrily from the Führer’s H.Q., on the grounds that the enemy’s intentions were not yet clear and that Hitler had not yet made a decision. This sounded well, but what it really meant was that the Führer, like Churchill a late-night worker, had gone off into a drugged sleep which no one dared interrupt. When he did finally wake up, it was mid-afternoon and D-Day was more than half over. Both night and the morning mist and cloud were gone, so that his armour had to resume their advance, not only late, but under air attack. Consequently, the only armoured formation near enough to the landing area to counter-attack on 6 June was 21 Panzer Division, with about 120 tanks.

The West Wall defences covering Caen were manned by 716 Infantry Division, commanded by Generalleutnant Wilhelm Richter, to whom Generalmajor Edgar Feuchtinger of 21 Panzer Division was subordinate. Richter wanted the parachutists mopped up at once and, according to standing orders, could commit some of Feuchtinger’s infantry and guns on his own responsibility; but he could not commit the armour, which was part of Rommel’s reserve—and Rommel was on his way back from Germany. Richter in turn was subordinate to General Erich Marcks of 84th Corps, while Feuchtinger was responsible also, in the event of invasion, to Geyr von Schweppenburg’s Panzer Group West. Caught in this cat’s cradle of command, Feuchtinger hesitated, waiting for the situation to clarify itself, and his division was lost. At 0200 hours, Richter ordered him to put in a full-scale divisional attack against the airborne landings east of the water barriers; had Feuchtinger complied immediately, the attack must have succeeded—for the two parachute brigades had been severely weakened by losses; their third, air-landing brigade, was not due to be flown in until evening, and there could be no early support from 3 British Infantry Division. If the parachutists blew the bridges, the Germans would have been unable to intervene quickly against the seaborne landing, but at the least, the left flank cover of the British dash for Caen would have been destroyed.

As it was, only those units of 21 Panzer Division to which Richter was empowered to issue orders actually moved. Among them was Oberstleutnant Rauch’s 192 Panzer Grenadier Regiment, whose II Battalion was directed against Bénouville at 0200. Leutnant Hans Höller was commanding a section of 75 mm SP guns in the 8th Heavy Company of II Battalion. They had been dug-in at Cairon, well-placed to meet the thrust of 3 Canadian Div. Now, they drove eastwards across the area where 3 British Div. was shortly to advance on Caen, and fought their way into Bénouville, now held by 7 Parachute Battalion. The original 21 Panzer Division had been part of the Afrika Korps, but had gone into captivity in Tunisia. Höller was one of the few who provided some continuity; he had served in Africa with 15 Panzer Division and been evacuated with multiple bullet wounds. “We got involved in heavy fighting with a strong parachute unit,” he said. “We managed to penetrate into half the village, but the parachutists fought bitterly and the exit leading to the coast could not be taken.” Realising this, Höller went off with two men to look for good defensive positions for his guns. A large building overlooking the Caen Canal offered an obvious vantage point, so they dashed towards it and began to climb the stairs to the roof. Actually, it was a maternity home, and there instantly occurred a comedy of errors and misunderstandings.

The matron, Madame Vion, told the British that a German officer, a serjeant, and a private, had forced their way in, despite her outraged protests, that she had shown them up the stairs, and that there one of their own anti-tank guns had mistaken them and opened fire on the building.3 This must have been Höller and his two men. but he had not the least idea that the building was a hospital, until he opened a door and found himself looking into a ward, “a disagreeable surprise”. Before he got there, while still on the stairs, he had been fired at by a German gun; but it was not one of his own anti-tanks, naturally. The fire came from a German naval vessel which was already under fire from the British and was fleeing up the Canal towards Caen, unaware that the front-line, such as it was, ran through the middle of Bénouville. There had been two of these ships, escaping from the sea-borne assault, which had just begun. They reached the bridge just as the commander of 6 Airborne Division, Major-General R. N. Gale, crossed it on foot.4 One was put out of action and ran ashore, where it was captured by parachutists; the other passed upstream, returning fire with a 2 cm gun, shooting up the parachutists, Leutnant Höller, and the Matron. “Of course, we were not allowed to fire back,” said Höller, “but this spook soon disappeared, without doing us any damage.” Had anyone been killed, yet another atrocity story would have been born.

At this stage, both the British and the Germans were mixed with civilians, and hampered by them. Höller had put his three 75 mm guns and the mortar troop into a nursery wood bordering the village and the chateau, part of which housed the maternity home. Protecting them was a group of panzer grenadiers. “About noon,” said Höller, “a very old man came staggering towards us from the direction of the enemy positions. He appeared, or was pretending to be, almost unable to walk. He came to a dead stop directly opposite part of a hedge which hid one of our guns. Then, he turned round and stumbled back towards the enemy, while the men discussed whether or not it was wise to let him get away.” The British parachutists, similarly, were not pleased to be enthusiastically greeted by French civilians, since it was rather like marking their positions with a red flag and inviting the enemy to fire. That was thoughtlessness, but the old man was probably deliberately brave, for, a few minutes after he had staggered away, two British tanks appeared and fired on the German gun which he had located. The Germans fired back, knocking out one tank and causing the other to disappear quickly. Strict military logic had demanded the death of the old man and the occupation of the maternity home; but these were the first few hours of the very first day. Elementary decency still prevailed over the instinct of self-preservation, in the same way that butter takes a few seconds before it melts on top of a red-hot stove.

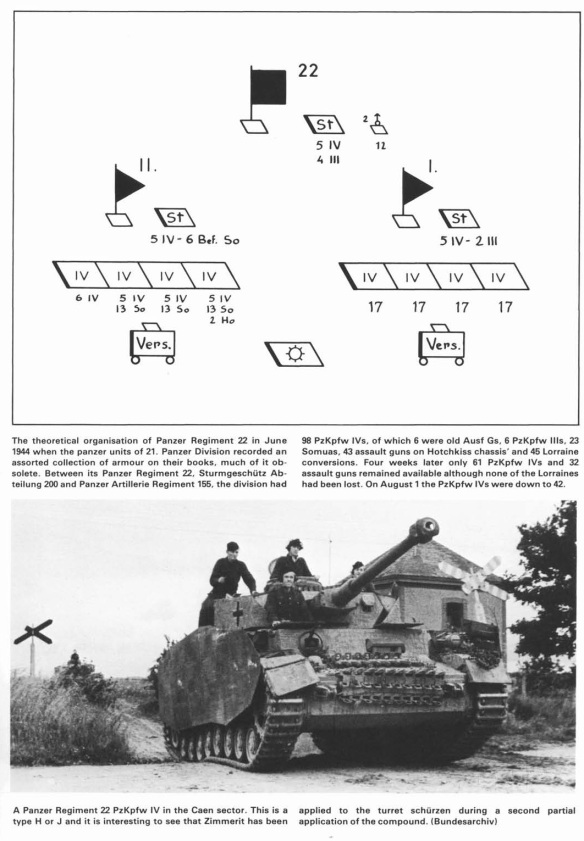

“We saw Caen at the horizon as a burning, smoking town”, said Werner Kortenhaus of 4th Company, Panzer Regiment 22, as the tanks moved off at 0800. “The march was slow and difficult, the roads choked by other units moving up and by refugees fleeing from Caen.” Having been alerted at 0100, the tank element of 21 Panzer Division, the four companies of Panzer Regiment 22, had done nothing for some six or seven hours, while the situation was obscure and the commanders argued. Now, the seaborne troops were landing, and the situation was clarifying; but the order now being obeyed by the four tank companies was General Richter’s original directive, for the whole of 21 Panzer Division to attack the airborne landings east of the Orne. At 1230, the delayed British advance on Caen began, and half-an-hour later, at 1300, Feuchtinger issued another order. The tank force was to be split. 1st, 2nd, and 3rd Companies were to attack the seaborne landings; 4th Company was to join Oberstleutnant Freiherr Hans von Luck’s Panzer Grenadier Regiment 125, together with some of the division’s artillery, mortar, and reconnaissance units, and attack the parachutists. The reason was that 21 Panzer Division had been transferred to General Marcks of 84th Corps, that Marcks realised that the main threat lay in the seaborne assault by 3 British Infantry Division, but that he had been told to expect no help from 12 S.S. Panzer Grenadier Division, still held back as strategic reserve, and that therefore he must contain the airborne bridgehead with what he had. As originally disposed, 21 Panzer Division had been well-placed to encounter both assaults: the infantry and anti-tank guns dug in as a screen between Caen and the sea, the armour held behind Caen, so that it could drive left or right of the water barriers, as the situation required. Oberstleutnant Rauch’s Panzer Grenadier Regiment 192 had merely to stay where it was, north of Caen, to be effective; while Oberstleutnant von Luck’s Panzer Grenadier Regiment 125 could have attacked the parachutists much earlier, had they been given permission. Richter’s orders had had the effect of clearing the way for 3 British Infantry Division, for he had moved some of the infantry eastwards and some of the anti-tank guns westwards.