Noticing how narrow the sea was that separated it [Sicily] from Calabria, Roger, who was always avid for domination, was seized with the ambition of obtaining it. He figured that it would be of profit to him in two ways – that is, to his soul and to his body.

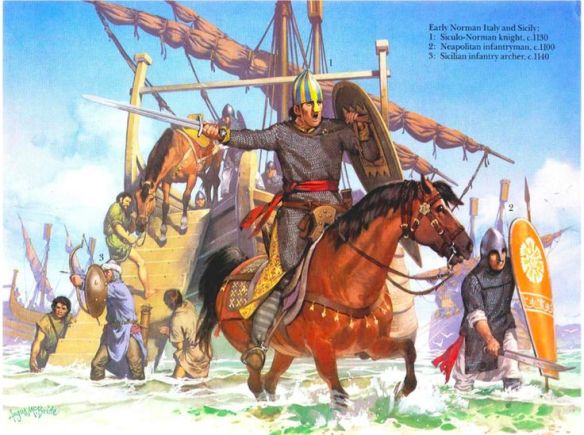

By reading Malaterra’s view of the motives behind the Norman invasion of Sicily, we understand that the decision to invade the island had been planned by Roger just a few months before the actual invasion, which is surely not the case. In fact, From the synod at Melfi in August 1059, Robert Guiscard had been invested by Pope Nicholas II as `future duke of Sicily’, thus laying the foundation for the conquest of the island which would serve both parties. The Normans would profit from the conquest of an island as fertile and rich as Sicily, while the Catholic church would reap the fruits of glory for taking the island away from the infidels after almost two centuries and not allowing it to fall under the jurisdiction of Constantinople – Sicily, along with Calabria and Illyria, had been brought under the authority of the patriarch of Constantinople by Constantine V (741-75), whose creation of Orthodox metropolitan sees there was seen as a result of the iconoclastic crisis of the period. The Norman invasion of Sicily, from the period between 1061 and the conquest of Palermo in 1072, consisted primarily of three major pitched battles between Norman and Muslim armies, two major sieges and one great amphibious operation conducted by a hybrid Norman fleet.

Sicily is covered with mountains (25 per cent) and hills (61 per cent). Etna dominates the geography of the island on the east coast (3,263 metres), while in the north there are three granite mountain groups, covered with forest, just short of 2,000 metres. These cover a zone from Milazzo to Termini and spread as far inland as Petralia and Nicosia. The coastlands of the northern part of the island, from Taormina to Trapani, present an alternation of narrow alluvial plains and rocky spurs which significantly hinders communications. The interior of Sicily is dominated by impermeable rocks and rounded hills separated by open valleys, with the harsh climate characterised by long summer droughts and low rainfall, creating a sharp contrast with the coast. Finally, along the southern shore, low cliffs alternate with alluvial plains, while between Mazara and Trapani a series of broad marine platforms can be identified.

The enemies that the Normans were to face in Sicily were the Muslim dynasty of the Aghlavids, who by the beginning of the ninth century had overwhelmed all of modern Tunisia and Libya and were launching numerous raids on Calabria and Sicily itself. They established themselves permanently on the island in 827 when, taking advantage of a local rebellion by the governor Euphemius, they landed in full strength and stormed Palermo in 830. Their progress was slow, a prelude to the Norman pace of conquest; in fact, it took them five decades to subdue the island, which eventually capitulated because of poor leadership and the empire’s much more pressing wars in the East against the Arabs. The Aghlavids were eventually ousted in 909 by the Fatimids, who directly ruled the island for almost four decades. In 947, they dispatched a governor from Ifriqiya to crush a local rebellion at Palermo, and his governorship was to lead to the establishment of the local Muslim dynasty of the Kalbites, which ruled for more than ninety years. Nominally still vassals of the Fatimids and, practically after 972, of the Zirid viceroys in Ifriqiya, the Kalbites enjoyed a significant degree of autonomy and self-sufficiency.

The breakdown of the political consensus at the beginning of the eleventh century and the emergence of separatist forces were also combined with a great migration from North Africa, because of civil-religious conflicts between Sunni and Shi’a factions. Several Muslim naval raids also took place, aiming at southern Italy and western Greece. When the last Kalbite emir, al-Hasan, was assassinated in 1052, the island was divided into three contending principalities: the south and centre was ruled by Ibn al-Hawas, who also commanded the key fortresses of Agrigento (in the west coast) and Castrogiovanni (in the centre), the west by Abd-Allah ibn Manqut and the east by Ibn al-Timnah, based in Catania. Ibn al-Timnah emerged in the Sicilian political scene in 1053 and in the following years he established himself in Syracuse. His conflict with al-Hawas and his gradual loss of power in the east of the island forced the Muslim emir to contact Roger Hauteville in February 1061. Al-Timnah actively assisted the Normans in their invasion of the island by providing troops, guides, money and supplies until his death in 1062, in the vain hope that his allies, once defeating al-Hawas, would hand the island back to him.

Prior to the main invasion of the island of Sicily in May 1061, two other reconnaissance missions took place, one conducted by Roger with a force of sixty knights who landed close to Messina in the summer of 1060, and a second taking place two months before the main invasion and led by Guiscard, who targeted the surrounding areas of Messina. For the main amphibious operation in May 1061, Roger landed his troops in the Santa-Maria del Faro, just a few kilometres south, in order to avoid the Muslim ship-patrols which were sweeping the coasts. His advance guard took the Muslim garrison of Messina by surprise and overran them.

Malaterra notes a military tactic employed by Roger to enter the city by force, according to which his troops performed a feigned retreat in order to draw the Muslim garrison out of the city, and then turned back and attacked them fiercely. Whether this was, indeed, a military tactic well practised and employed by Roger or was just presented that way by the chronicler we will never know for sure; what is certain, however, and has to be underlined, is the frequency with which Normans were using this particular tactic, with the most characteristic examples being those of Hastings and Dyrrhachium.

Following Roger’s success at Messina, Guiscard crossed the straits of Scylla and Charybdis with the main Norman force of 1000 knights and 1000 infantry. The Norman army marched west, capturing Rometta with no great difficulty, but then failed to take Centuripe because of the city’s strong fortifications, the lack of time and the danger of a relief army arriving. Their next target was Castrogiovanni, the headquarters of the local emir, Ibn al-Hawas, and of great strategic importance for the control of the central plateau of the island, situated as it was west of Mount Etna and Val Demone in central Sicily. As the Normans were far away from their bases in the north-east and in hostile territory, largely relying on the local Christian Orthodox population for supplies, and because of the menacing approach of winter, they could not afford to stay in Sicily for long. In their usual non-Vegetian tactics, Robert and Roger were active in seeking battle with their enemy, who was nowhere to be found, pillaging their way down to Castrogiovanni and killing many of the inhabitants in order to provoke the emir to face them in pitched battle.

In the summer of 1061 the first of the major pitched battles between the Normans and the Muslims took place close to the fortress of Castrogiovanni and on the banks of the River Dittaino. The heavily outnumbered force commanded by Robert Guiscard inflicted a heavy defeat on the Muslim army, a tremendously important victory for Norman morale, considering that the Norman conquest of Sicily was still in its very early stages. There were no significant gains for the Normans, because with the escape of many Muslims (including Ibn al-Hawas) back to their base and with the campaigning season almost over, they could not afford to stay in hostile territory any longer. Hence, we are informed of Roger’s decision to retire back to Messina after a successful pillaging expedition to Agrigento.

Despite such a promising beginning, the conquest of Sicily proved a very lengthy process. By the end of 1061, the Normans had managed to take control of most of the areas of the north-east of the island, mainly inhabited by Greek Orthodox Christians.

The anti-Muslim feeling amongst the local population had emerged as a decisive factor from the Byzantine expedition of 1038-41, owing to the aggressive Kalbite policy of extending the Muslim colonies in the south and east of the island. But once the Muslims had recovered from their initial shock, they resisted stoutly for many more years. The main reason for the difficulty in conquering the island was certainly the scarcity of occasions when the Normans could deploy enough of their forces to Sicily, with Roger having just a few hundred knights to maintain his dominions and launch plundering expeditions when necessary. Throughout the year 1062, no major conflicts between the Normans and the Muslims occurred, mostly because of Roger’s strife with his brother.

In order to understand why Robert Guiscard could ill-afford to send many troops to his brother in Sicily, apart from their strife in 1062, one has to consider how Apulia was a far more important operational theatre than Sicily. Looking at Guiscard’s operations in the region, he had to deal with the conquests of Brindisi (recaptured by the Byzantines soon after) and Oria in 1062, along with a serious rebellion at Cosenza in Calabria in 1064-5, which took several months to suppress. Robert’s attention turned to Apulia once again after 1065, capturing Vieste and Otranto by the end of 1066. Soon afterwards, however, he was about to face the most dangerous rebellion against his power in Apulia, headed by Amicus, Joscelin of Molfetta, Roger Toutebove and two of his own nephews, Geoffrey of Conversano and Abelard. The way in which the operational theatres of Apulia and Sicily are connected is clear. Thus, in order to examine properly the Norman invasion of Sicily a close eye should be kept on the political and military developments across the straits of Messina.

After the settlement of the strife between Robert and his brother Roger in the spring of 1063, we can observe a slight change of tactics used by Roger to conduct his warfare in Sicily. In order to diminish his disadvantage of having a very small number of stipendiary knights at his disposal, he used the mobility and speed of the horses to ambush the Muslims, with the most characteristic example being that of the Norman victory at Cerami, in the early summer of 1063. Important as it was, however, the victory at Cerami did not bring the Normans closer to conquering the island but merely confirmed their hold on the north-eastern part. Roger simply maintained his army on a hand-to-mouth basis, relying on plundering raids in the south and southwest of the island, with his brother very rarely being able to send reinforcements from Apulia.

Following the events at Cerami in 1063, we have very little information on what took place in Sicily over the next four years. This suggests either that Roger had only a few troops at his disposal, or that the Muslims were putting up a vigorous resistance to the Norman expansion. Nonetheless, we are informed that Roger maintained pressure on his enemies and carried on with his advance, albeit gradually, along the north coast towards the capital. The town of Petralia, which had been abandoned in 1062, was reoccupied and converted into Roger’s main base in Sicily, with its fortifications being improved in 1066; in fact, Roger’s attention to the west and north is marked by his moving of his main base from Troina to Petralia. By 1068, the raids conducted by Roger were affecting the entire northern coast, reaching close to Palermo itself and, in that year, he was able to inflict a bloody defeat on the Muslims at Misilmeri, only 12 kilometres south-east of the Muslim capital of the island, Palermo.