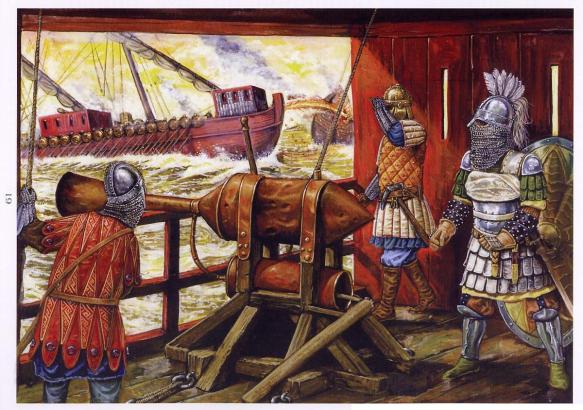

A modern depiction of a Byzantine flamethrowing warship, using Greek Fire against an enemy ship (probably of the opponent Muslim fleets). In the foreground: the mechanism and the siphon of ejection of Greek fire in the interior of a Byzantine Dromon (artwork by Giorgio Albertini)

By John H. Pryor

In spite of the fact that some crews in Byzantine fleets at various times were well regarded, for example the Mardaites of the theme of the Kibyrrhaiōtai, there is little evidence to suggest that, in general, Byzantine seamen were so skilled that this gave Byzantine fleets any edge over their opponents. It is true that Byzantine squadrons managed to defeat the Russians on all occasions when they attacked Constantinople: in 860, probably in 907 under Oleg of Kiev, in 941 under Igor, and in 1043 under Jaroslav. A fleet also defeated the Russians on the Danube in 972. However, rather than being attributable to any qualities of Byzantine seamen, these victories were due to the triple advantages of Greek Fire, dromons and chelandia being much larger than the Norse river boats of the Russians, and (except in 972) being able to fight in home waters against an enemy far from home. The last is true also of the defeat of the Muslim assaults on Constantinople in 674–80 and in 717–18. In both cases, it was the advantage of home waters against the disadvantage of campaigning hundreds of miles from sources of supplies, the problems faced by the Muslims of surviving on campaign through the winter, and Greek Fire that proved decisive. The same is probably true of the victories over the fleets of Thomas the Slav in 822–3.

In general, the record of Byzantine fleets from the seventh to the tenth centuries was hardly impressive. To be sure, they did achieve some notable victories: the defeat of the Tunisians off Syracuse in 827–8, the defeat of a Muslim fleet under Abū Dīnār off Cape Chelidonia in 842, the victory of Nikētas Ooryphas over the Cretans in the Gulf of Corinth in 879 and of Nasar over the Tunisians off Punta Stilo in 880, the victory of Himerios on the day of St Thomas (6 October), probably in 905, the defeat of Leo of Tripoli off Lemnos in 921–2, the victory of Basil Hexamilitēs over the fleet of Tarsos in 956, and the defeat of an Egyptian squadron off Cyprus in 963. Against that record, however, have to be balanced many disastrous defeats: of Constans II at the battle of the masts off Phoeinix in 655, of Theophilos, the stratēgos of the Kibyrrhaiōtai, off Attaleia in 790, a defeat off Thasos in 839, the defeat of Constantine Condomytēs off Syracuse in 859, the annihilation of a fleet off Milazzo in 888, a defeat off Messina in 901, the disastrous defeat of Himerios north of Chios in 911, the defeat of a Byzantine expedition in the Straits of Messina in 965, and of fleets off Tripoli in 975 and 998.

Although the tide of Byzantine naval success ebbed and flowed over the centuries, as other circumstances dictated, nothing suggests that the quality of the Empire’s seamen was in any way decisive. Indeed, there are occasional pieces of evidence that suggest that all was not always happy in the fleets. Some time between 823 and 825, John Echimos, the ‘deputy governor’, (ek prosōpou), the acting stratēgos, of the theme of the Kibyrrhaiōtai, confiscated the properties of seamen of the fleet. After he had become a monk and taken the name Antony, later to become St Antony the Younger, he was interrogated as to his reasons for doing so on the orders of the new emperor, Theophilos (829–42). According to the author of his Life, his explanation was that they had been partisans of Thomas the Slav in his rebellion of 821–3 and were ‘hostile to Christians’, thus implying that they were iconoclasts, and that he had confiscated their property and given it to supporters of Theophilos’ father, Michael II (820–9). In spite of this explanation, the emperor initially imprisoned him and had him interrogated, suggesting that there was more to the story and that he rejected the explanation. The fleet of the Kibyrrhaiōtai had, indeed, joined Thomas the Slav, as it was also later to join the rebellions of Bardas Sklēros in 976–9 and Bardas Phōkas in 987–9, and it is clear that, at times, there must have been serious disaffection in what was the front-line fleet of the Empire in the ninth and tenth centuries.

In 880, the expedition sent under the command of Nasar, the droungarios touploimou, to counter an attack in the Ionian sea by a Muslim fleet from Tunisia was forced to a temporary halt at Methōnē by the desertion of a large part of the crews. Why they deserted is unknown, but we can be fairly sure that it was not a simple question of their having ‘lost their nerve’, as the Vita Basilii suggested.