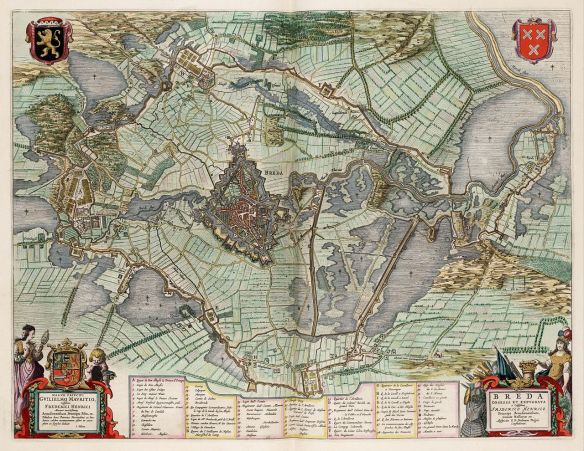

Beleg van Breda (1637) by Frederik Hendrik

The Loss of Breda 1637

Spain’s mounting problems concerned the Empire because they undermined Philip IV’s war against the Dutch. A Spanish success in the Netherlands would enable Ferdinand III to withdraw his troops from Luxembourg, while a Spanish defeat would free France to reinforce its army in Germany. As the war dragged on, Ferdinand urged his cousin to at least settle with the Dutch and concentrate on the conflict with France. Spain viewed the events in the Empire with similar impatience, failing to understand why the emperor had not been able to crush Sweden after Nördlingen. Imperial commanders repeatedly promised Spain cooperation during the winter planning rounds, only to march in the opposite direction when the campaign opened to stop Swedish attacks on Saxony or Bohemia.

The effects were felt in 1637, dispelling the optimism following the Year of Corbie. The unexpected success of the unplanned invasion of France in 1636 encouraged Olivares to switch three-sevenths of the then 65,000-strong Army of Flanders to Artois and Hainault for an invasion of Picardy. However, he refused to surrender the remaining outposts on the Lower Rhine to obtain peace with the Dutch, tying down the bulk of the other troops in garrisons. Conscious that the strike force was insufficient, he pressed Ferdinand to make diversions along the Moselle and in Alsace that failed to materialize.

While Spain massed in the south, in the Republic Frederick Henry staked his political capital on a major blow against the northern frontier. He was under growing pressure to negotiate. Though he managed to sideline Adriaen Pauw, the leader of the Dutch peace party, by sending him as ambassador to Paris in 1636, his support was falling away. The open French alliance after 1635 split opinion among the Gomarist militants who had been the war’s principal backers, because Frederick Henry had promised Richelieu he would accept Catholicism in conquered areas. Moreover, Amsterdam merchants had no interest in liberating Antwerp, a city that might resume its former place as the region’s commercial centre. Increasingly, support for the war was restricted to three groups. The southern provinces of Zeeland, Utrecht and Gelderland still felt vulnerable and wanted Frederick Henry to capture more land beyond the Rhine as a buffer. These provinces were also home to the majority of Belgian Calvinist refugees who hoped military success would enable them to return home. Finally, there were those who benefited materially from the war, notably shareholders in the West India Company, an organization that proved remarkably successful in attracting investors from across the Republic. These groups were still strong in 1637, but it was significant that the Holland States implemented the first budget cut since the Twelve Years Truce, disbanding the most recently raised regiments in the winter of 1636–7.

Frederick Henry seized his chance to attack Breda on 21 July while the Spanish were still collecting troops on the southern frontier. Fernando had to march north again. Unable to break the Dutch siege, he tried to distract the stadholder by taking Venlo and Roermond. His absence enabled Cardinal de la Valette and 17,000 French to capture Landrecies and Maubeuge, forcing Fernando to retrace his steps southwards. Breda fell on 7 October, removing the last of Spain’s gains from its year of victories in 1625. The defeat prompted Olivares to revert to his Dutch strategy, instructing Fernando on 17 March 1638 to make a major effort to compel the Republic to accept reasonable terms in negotiations that were now reopened. Victory was no longer expected; the aim now was to leave the war with honour.

The End of Imperial Assistance 1638–9

The planned Spanish offensive in Artois was aborted when well-coordinated Franco-Dutch attacks hit both the northern and southern frontiers of the Spanish Netherlands simultaneously in May 1638. Frederick Henry and 22,000 Dutch marched on Antwerp, while Marshal Châtillon and 13,000 French thrust towards St Omer, covered by La Force and another 16,000 troops in Picardy. The Spanish were pinned, but Frederick Henry retreated after a sortie from Antwerp captured 2,500 of the besiegers at Kallo, one of the worst Dutch defeats of the war. The reverse undermined the stadholder whose increasingly regal behaviour was attracting republican criticism. Piccolomini was obliged, as usual, to wait until sufficient troops had been collected to protect Cologne, before marching west to help Prince Tommaso of Savoy relieve St Omer in July. The French took a few minor posts and recovered Le Câtelet, but Louis XIII was disappointed.

The French command was entrusted to Richelieu’s relative, La Meilleraye, who marched on Hesdin with 14,000 men in 1639, covered by Châtillon and a similar number on the frontier. Feuquières and 20,000 troops were sent to pin Piccolomini in Luxembourg and prevent further imperial intervention by capturing Thionville, the town that gave access to the area between Namur and Koblenz. Spain had withheld its subsidy to compel Ferdinand to leave Piccolomini in Luxembourg. After being joined by Duke Charles of Lorraine, Piccolomini appeared unexpectedly at sunrise on 7 June with 14,000 Imperialists and Spanish outside Feuquières’ siege lines at Thionville. Unable to assemble from their billets, the French were routed, losing 7,000 prisoners and some of the best regiments in their army. Louis XIII’s presence with the main army meant the siege of Hesdin could not be abandoned without a serious loss of prestige and it was continued until the place surrendered on 29 June. Most of Piccolomini’s forces were then withdrawn from the area to confront the Swedish invasion of Bohemia, bringing the era of direct military cooperation between Spain and the emperor to an end.

The Downs

The diversion of French resources to Flanders and to the eastern end of the Pyrenees allowed Spain to collect a new armada at La Coruña tasked with breaking the blockade of Dunkirk and landing substantial reinforcements for a new offensive in 1640. It was a major undertaking, and negotiations were opened with England in February to secure naval assistance. The Spanish fleet comprised 70 warships and 30 transports, totalling 36,000 tonnes, with 6,500 sailors, 8,000 marines and 9,000 troops to reinforce the Army of Flanders. Admiral Sourdis raided the Spanish coast in June and August, but was unable to disrupt the preparations and withdrew exhausted, leaving it to the Dutch to intercept the armada when it finally sailed on 27 August.

Maarten Tromp attacked with seventeen ships as the Spanish entered the English Channel on 16 September. Oquendo was overconfident and failed to issue adequate instructions to his subordinates. He remained wedded to the traditional tactics of duels between rival ships, having won the battle off Pernambuco in 1631 by destroying the Dutch flagship. Tromp sailed in tight formation line ahead, so that each time a Spanish ship ventured to attack it was met by his combined firepower. An experienced Portuguese officer observed that ‘Oquendo, [was] like a brave bull which is ferociously attacked by a pack of hounds and blindly charges those which assault him, so he with his ship full of dead, wounded and mutilated gallantly tacked upon those which were nearest him.’ Despite having pinned Tromp and his fleet against the French coast, Oquendo gave up around 3 p.m. because his own ship was too battered to continue. The two fleets were becalmed the next day, but Tromp was joined by another seventeen warships on 18 September and renewed the fight until he ran low on powder. With Dunkirk still blockaded, Oquendo realized there would be no safe port in which he could refit if he sailed beyond Calais, so he crossed the Channel to anchor at the Downs off Deal in Kent, believing the English would provide assistance.

Admiral Pennington appeared with thirty ships, but only to uphold English neutrality. The English did help ferry the troops and 3 million escudos in cash to Flanders by November, but apart from selling some overpriced gunpowder, did little to help the Spanish fleet. Most of the smaller ships escaped past the Dutch into Dunkirk, but Tromp had been reinforced by large armed merchantmen from the Dutch Indies companies’ fleets and now had 103 warships to Oquendo’s 46. Tromp entered English waters to attack on the morning of 21 October. Oquendo beached his twelve lighter ships and fought his way out with the rest. His flagship was hit 1,700 times, but made it to Mardyck. Ten of the beached ships were refloated early in November and also escaped to Flanders.

Tromp was severely criticized for his failure to capture the Spanish flagship. Oquendo refitted in Dunkirk and sailed back to Spain early the next year with 24 ships. While 1,500 troops had been intercepted, part of the mission had been completed successfully and the Army of Flanders mustered 77,000 men in December 1639, while the navy still totalled 34,131 tonnes. Despite the continued blockade, Spain managed to convoy another 4,000 recruits to Flanders from 1640 until Dunkirk fell in 1646. Nonetheless, the campaign cost at least 35 ships, over 5,000 dead and 1,800 prisoners. Losses in 1638–40 totalled 100 warships, 12 admirals and 20,000 sailors, or the equivalent of ten Trafalgars.

Spain could not sustain this rate of attrition. The effort was in vain since the entire strategy was flawed. As the 1640 campaign again proved, it was impossible to mount an offensive either north or south as long as France and the Republic coordinated their attacks against both frontiers. While the Dutch were repulsed, the French captured Arras on 9 August after a two-month siege. Following the armada’s defeat and the outbreak of the Catalan revolt, this was a major blow. Thousands fled to Lille as the French overran the rest of Artois. More bad news arrived in November when the French relieved Turin, but the situation worsened in December as the Portuguese rose in revolt.

The repeated setbacks altered the balance of Austro-Spanish relations. Having paid a respectable 426,000 florins to Austria in 1640, Spain was in no position to help any longer, delivering only 12,000 fl. the following year and 60,000 as a loan in 1642. Piccolomini had been recalled from Luxembourg and the emperor cancelled the Hohentwiel operation for which Spain had paid the Tirol to raise 4,000 men. Spanish influence declined further as its experienced ambassador, Castañada, returned to Madrid in 1641, whereas Ferdinand was now represented in Madrid by Field Marshal Grana, a forceful character who shared the emperor’s opinion that Spain was wasting its resources and squandering opportunities for peace.

Clutching at Straws

Olivares grew increasingly desperate, renewing contacts with the French malcontents who had been plotting against Richelieu since 1636. Several had fled to London where they backed Spain’s fruitless efforts to persuade Charles I to join an alliance against Louis XIII. The outbreak of the British Civil Wars rendered this a lost cause. By 1640 Olivares had turned his attention to a group around Count Soissons who had fled to the sovereign duchy of Bouillon on the Netherlands frontier. Encouraged by the ambitious marquis de Cinq Mars, they believed they had the support of the French queen, Anne of Austria, and that a show of force would prompt Louis to dismiss Richelieu. Olivares regarded the conspirators as the ‘sole means of salvation from shipwreck’ and promised support.

The malcontents in exile in England were supposed to sail with a scratch fleet to raise the Huguenots in Guyenne, but never arrived. Details of the plot had already reached Richelieu by April 1641 and he altered his campaign plan to counter it, massing 12,000 men under Châtillon in the Champagne to block Soissons in Bouillon. The plotters panicked. Frédéric-Maurice de Bouillon declared that his current capacity as French commander in Italy prevented him from joining the rebels’ planned expedition. He nonetheless urged Soissons to act. General Lamboy arrived in Bouillon with 7,000 Spanish and Imperialists in June to give 9,500 troops altogether and they advanced south, defeating Châtillon at La Marfée on 9 July. Any hope of exploiting the victory was wrecked by Soissons’ death, allegedly self-inflicted by raising his visor with a loaded pistol that accidentally went off. The revolt collapsed, enabling Richelieu to mop up the plotters by the following June once he had gathered more evidence and was certain of Louis XIII’s support. Cinq Mars was executed, while Bouillon escaped death by converting to Catholicism and surrendering his duchy. Implicated in treason again, Louis’ brother Gaston fled to Savoy.

Duke Charles of Lorraine had meanwhile accepted French terms on 2 April 1641 in order to recover his duchy as a French fief. However, his failure to assist France during Soissons’ invasion raised suspicions and led to his expulsion again in August. He invaded the duchy with 5,000 men from Luxembourg in April 1642, scoring a few minor successes, but lacked the means to exploit these and was back across the frontier within five months. The situation returned to that prior to April 1641, except that the duke had recaptured Sierck, La Mothe and Longwy.

The intervention of Soissons and Lorraine at least frustrated any immediate exploitation of the capture of Arras by France. Richelieu then switched resources to Catalonia, while the Dutch were distracted by the return of the war to north-west Germany at the beginning of 1642. At last the Spanish were able to go onto the offensive, but rather than being intended to force the Dutch to make peace, operations were now simply to distract France from attacking Spain itself. The new governor of the Spanish Netherlands, de Melo, advanced up the Scheldt into Artois, retaking Lens (19 April) and La Basseé (11 May). The two small French armies in the area under Harcourt and Guiche failed to coordinate an effective defence. De Melo and 19,000 troops caught Guiche’s 10,000 men at the abbey of Honnecourt on 26 May, killing 3,200 and capturing 3,400 along with most of the baggage and the pay chest. The victory allowed de Melo to complete the recovery of northern Artois.