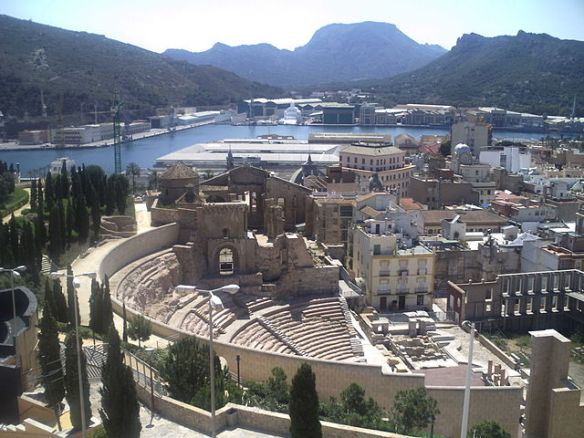

The Roman Theatre of Carthago Nova and Cathedral ruins of Cartagena.

Publius Cornelius Scipio Africanus spent the winter of 210–209 BCE strengthening ties with the local tribes and gathering intelligence on his intended target. Novo Carthago was the primary port of entry for whatever assistance came from Carthage: it held the treasury, it contained a massive armory, and it was where the hostages held to assure the cooperation of the Spanish tribes were kept. Further, it was the primary manufacturing center, especially for weapons. On the surface, Scipio’s attacking the main Carthaginian base seemed rather foolish given his relatively small force. The city was encircled with walls and surrounded by water on three sides—by a harbor and a lagoon. In reality it made perfect sense—as long as it could be captured quickly. Scipio had learned that the garrison numbered a mere 1,000 soldiers. The key was to make sure that the assault did not turn into a long siege, for that would give one or both of the Barcas the chance to march to the city’s relief. Why would the Carthaginians leave their main port and supply base so lightly defended? According to Polybius, it was their rivalry. “Each went his own way in pursuit of personal ambitions, which would hardly have been fulfilled by electing to remain at New Carthage and ensure its security.”

The key to a successful attack lay in the nature of the lagoon on the city’s northern side. After questioning local fishermen who had navigated it, he learned that in many places the lagoon was not very deep; according to Appian, it was chest high at the water’s crest and knee-high when the water ebbed, which it did every afternoon, when strong north winds blew the waters through the canal and into the harbor. If he could hold the defenders’ attention on a landward assault, a small force would be able to sneak across the lagoon and attack an undefended portion of wall.

He divulged none of his plans to any of his subordinates save one, his longtime friend and co-commander Gaius Laelius. Rumors, on the other hand, ran rampant throughout the army and the population, for which Scipio was grateful; the clot of stories would cloud the single one that was true. In the spring of 209 he led 25,000 infantry and 2,500 cavalry down the coast, leaving 3,000 infantry and 500 cavalry to hold his base at Tarraco. According to both Polybius and Livy, Scipio’s army made the march of roughly 300 miles (2,600 Greek stadia) in a week. An army marching 20–25 miles in a day in the nineteenth century was considered to be making good time. Both sources say that the fleet moved along the coast at the same speed. His arrival was certainly a surprise to the citizens and garrison of the city.

The lagoon (which no longer exists) was located on the north side, and the harbor to the south. The peninsula itself was reportedly only 300 yards wide, and Polybius asserts that the circumference of the walls was 22 miles. The city was built on five hills with a sixth outside the city at the base of the peninsula. That was where Scipio established his camp, building defenses on the side not facing the city just in case a relief force should appear and to give his army maneuvering room on the side nearest the city gates. The 1,000 soldiers inside were commanded by Mago (not the same Mago as Hannibal’s brother, who was in another part of Spain), who quickly drafted 2,000 citizens and armed them. When dawn broke and he saw the Romans preparing for an assault and Laelius bringing the Roman ships into the harbor armed with missile-throwing weaponry, Mago assigned his civilians to cover the walls while he placed half his soldiers on a hill near the harbor. The other half he kept in the citadel. As it turns out, the two veteran units were not designated to act as mobile reserves, which would have been the proper assignment, but to be in place for a last stand. This implies that Mago all but conceded the front gates and walls to the Romans.

Before the attack began, Scipio addressed his troops, reassuring them that there was no relief force readily available, that the garrison was small, that they would be acquiring great wealth at the expense of the enemy, and (best of all) that he had been informed in a dream that the god Neptune had promised assistance. He, of course, knew of the nature of the lagoon’s fluctuating waters, but, according to Livy, “made it out to be a miracle and a case of divine intervention” on behalf of the Romans. Polybius uses this as an illustration of Scipio’s genius: “This shrewd combination of accurate calculation with the promise of gold crowns and the assurance of the help of Providence created great enthusiasm among the young soldiers and raised their spirits.”

Just as the Romans were preparing for their assault, Mago launched a spoiling attack using the civilians, who came pouring out of the city gate. They gave a good account of themselves, but ultimately were both outnumbered and outclassed. When they finally broke and ran back for the city, they were barely able to get the gates closed behind them before the Romans broke through. Scipio quickly sent in 2,000 men with ladders to scale the walls, which, unfortunately for the Romans, were taller than the ladders. Again the civilians proved themselves surprisingly capable by keeping the Romans from reaching the crest; further, overloaded ladders broke and tumbled soldiers to the ground. By midafternoon Scipio called a halt. The defenders were catching their breath and hoping this signaled the beginning of a more traditional siege when the Romans started the assault again. The actions of the first attack were repeated in the second, but neither the Romans nor the defenders showed weakness or hesitation. At this point, defenders from around the walls were called to the landward defenses to aid in that quarter.

That was what Scipio had been waiting for. As the afternoon drew toward evening, his knowledge of the lagoon waters came into play. He led 500 men across the lagoon in the shallow areas and scaled the now-undefended walls on the north side of the city. Once inside they made their way to the gates and hit the defenders from the rear. Roman soldiers were hacking at the gates from the outside when they were opened from within. The civilians broke for their homes, pursued by the Romans who also attacked the 500 soldiers on the harbor-side hill, which had been dodging missile fire and assaults. Butchery of civilians began, stopped only when Mago surrendered the citadel, which he quickly did.

Within a day’s fighting Scipio had seized the major prize of all Iberia. Scipio had made a deliberate attack using all of his forces but the cavalry. The infantry assault at the gates coupled with the pounding from the ships and the assault of marines from that quarter made his march a complete surprise. The frontal assault, pressed hard, was key to the entire action. Had he relied on merely the lagoon crossing he would have been met by stout resistance on the walls, which, according to Polybius, were manned at all points. By launching his main attack at the gates he would probably have broken through sooner or later, but that was what caused the abandoning of the defense from the lagoon side.

Perhaps just as important as capturing the city and its assets—as well as freeing the hostages the Carthaginians had held—was what Scipio did after the battle was over and the spoils divided. He immediately began training his men in a new style of fighting, along the lines of what he had learned in action against Hannibal. The Roman way of fighting was unimaginative, in his view; Scipio trained the legions to employ tactics more flexible than the traditional Roman frontal attack, which depended entirely on the sheer weight of manpower. He had seen that fail at Cannae. To most senior Romans, the traditional way of fighting exhibited the hallowed concept of virtus, virtue, and the belief that deception was dishonest. Perhaps this was a variant on the Greek hoplite attitude, as we saw with Alexander: that real men only fought face to face.

The youthful Scipio was willing to break with the old ways. Bitter experience from facing Hannibal had already convinced him that learning from the victors was the key to beating them at their own game. With Novo Carthago he had come into possession not only of a huge arsenal but also the sword makers who specialized in crafting the Spanish sword. With a steady supply of the new weapons he began training his men.

Not many details as to how he did this are available. Nonetheless we do know that he kept the maniples but reorganized them into cohorts. The maniples consisted of two centuries of 80 men each and the cohorts became the next larger unit, containing three maniples, numbering 480 men. Ten cohorts constituted a legion. The result was that the basic tactical unit remained the same, but the cohort was made more flexible, so that it could be moved around the battlefield more easily than the legion. As Goldsworthy observes, “The old lines of the manipular legion were not effective tactical units for independent operations. The cohort, with its own command structure and with men used to working together, may well have fulfilled a need for forces smaller than a legion.” Movement on the battlefield—in a direction other than straight ahead—was one of Scipio’s significant contributions to the Roman army’s organization and behavior.