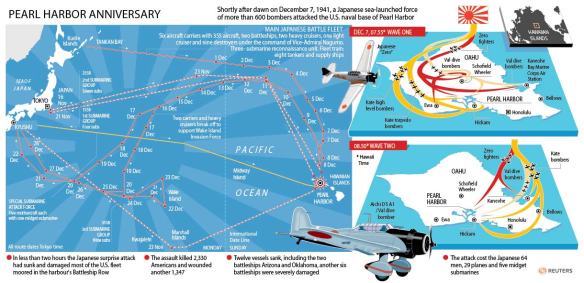

President Franklin D. Roosevelt ordered the U. S. Pacific fleet moved to this shallow harbor in Hawaii in May 1940, thousands of miles from its base at San Diego. The idea was to deter a Japanese assault on Southeast Asia. Instead, American-Japanese relations continued to deteriorate toward war over the course of 1941. An Imperial Conference convened on September 6 made the decision for war. Japanese forces immediately mobilized and the Navy began planning the attack on Pearl. Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto ordered preparations for the attack on November 1. A final peace effort by Japanese diplomats failed in late November. A powerful warfleet, Strike Force Kido Butai, sortied from the Kurils on November 26. It comprised six aircraft carriers and many heavy escorts, destroyers, and submarines. The flagship of Vice Admiral Chuichi Nagumo flew the famous “Z” flag, which fluttered above victories over Russia at Port Arthur in 1904 and the Tsushima Strait in 1905.

After 12 days undetected at sea, facilitated by refueling from tankers, the carriers received the attack signal: “Climb Mount Niitaka.” Washington had broken the Japanese diplomatic code but not the naval code. Earlier in the day the War Department sent warnings to Pearl and Manila of an anticipated Japanese assault. The attack, if it came, was expected to fall on the Philippines; no one considered that the Japanese might be so daring as to hit Pearl. In any event, the warning to Pearl was delayed by a black comedy of technical and human errors and did not arrive in time. The battleships of the U. S. Pacific Fleet were therefore still neatly docked on a quiet Sunday morning and caught wholly unawares by the Japanese naval air attack. The first attack wave achieved total surprise just after 7:00 A. M. on Sunday morning, December 7th, 1941. It began before the official Japanese declaration of war was delivered: it was delayed by lengthy transcription and slow decoding by the Japanese Embassy in Washington. The declaration of war belatedly delivered to Secretary of State Cordell Hull accused the United States of conspiring “with Great Britain and other countries to obstruct Japan’s efforts toward the establishment of peace through the creation of a new order in East Asia, and especially to preserve Anglo-American rights and interests by keeping Japan and China at war.” Americans later made much of the “sneak attack” at Pearl, though in Japanese operational terms the achievement of surprise was desirable and effective.

Surprise over Hawaii was total. The attack was designed by Commander Mitsuo Fuchida, a brilliantly innovative planner. It had as historical inspiration the stunning sinking of the Tsarist fleet at anchor at Port Arthur in 1904. Its spiritual inspiration and icon was even older: a famous samurai sword maneuver, the “i-ia” stroke that gutted or crippled an enemy before combat began. Its immediate progenitor was the RAF assault on the Italian fleet at Taranto. Fuchida led in the first wave, comprising 183 bombers, torpedo planes, and fighters. Splitting into four attack groups, the Japanese hit U. S. Army and Marine Corps air fields and bombed the ships lined up in “Battleship Row” in the harbor at Ford Island. A second wave of 170 planes attacked into more opposition, yet Japanese losses remained light. Within hours of the first explosions much of the Pacific Fleet was afire, sunk, or badly damaged. Among major capital ships, the battleship “Arizona” was gutted while the “Oklahoma” turtled. The battleships “California,” “Nevada,” and “West Virginia” were also sunk at anchor. On these and other ships, at the airstrips and elsewhere in Hawaii, the U. S. suffered 3,695 casualties, including 2,340 military personnel killed. Of the dead, 1,177 were aboard the “Arizona.” Another 48 civilians were killed. The USN saw 12 of its warships sunk or beached and another 9 badly damaged, while 164 Navy, Marine, or Army aircraft were destroyed and 159 more damaged. The Japanese lost a mere 29 planes and 64 men, including 9 navy crew killed on 5 midget submarines. However, the U. S. fleet carriers, the primary targets sought by Yamamoto and Fuchida, were fortuitously at sea on exercises and thus were spared. The “USS Enterprise” took some pilot casualties as it stretched its planes out from a distance to intercept the Japanese second wave. Admirals Nagumo and Yamamoto then clenched and refused to launch a third strike wave to destroy Pearl’s fuel and repair facilities. Had they done so, that action would have done more long-term damage to the Pacific Fleet even than dropping battleships in the shallow harbor.

In asking Congress for a declaration of war against Japan the next day, President Franklin Roosevelt declared December 7, 1941, a day “that will live in infamy.” Four days later Germany and Italy declared war on the United States, although they were not bound to do so by terms of the Tripartite Pact. Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini made that decision for war despite the fact that Japan was neutral in their war with the Soviet Union. The Pearl Harbor raid was accompanied by assaults on European colonial outposts all across Southeast Asia. There followed six months of uninterrupted Japanese victories in the Pacific and Southeast Asia, as the war clique in Tokyo enjoyed the illusion of a permanently risen imperial sun. Profound recriminations immediately followed in the United States. There were even suggestions that Roosevelt connived to allow the attack as a means of bringing Americans into the European war via the “Asian backdoor.” There is no evidence to substantiate the charge and much that refutes it. Roosevelt was actually deeply worried that the Japanese attack might deflect public attention away from the real strategic threat that came from Germany, toward a merely secondary threat in the Pacific. As with most complex conspiracy theories, it turns out that confusion and chaos are better explanations than low cunning or high treason.

Suggested Reading: Roberta Wohlstetter, Pearl Harbor (1962); Gordon Prange, At Dawn We Slept (1981).