King Edward the Confessor, a pious man, died childless on 5th January 1066. With no immediate heir, Harold Godwinson the Earl of Wessex had himself crowned King of England the following day. He was the foremost of a number of powerful earls. The Godwinson family owned land stretching from Cornwall to Kent in the south and East Anglia and part of the Midlands. Harold, who commanded the royal army, was immediately accepted as king by the Witanagemot, the Anglo-Saxon council of magnates. This was more a recognition of his military status than bloodline.

Harald Hardrada the king of Norway was a kinsman of the Canute family and had a distant claim to the English throne, which he decided to pursue. He began to prepare a Viking invasion of England in league with Harold’s disaffected brother Tostig, previously the Earl of Northumbria. Duke William of Normandy had extracted a vague oath of allegiance from Harold in 1064 following a shipwreck and enforced stay in Normandy. He was similarly a blood heir and had been promised the succession in 1051 by Edward. Norman influence at the Confessor’s court was, however, out manoeuvred by the rich and powerful Godwinson’s family, to which Harold belonged. William was outraged when he was not chosen and likewise prepared for invasion.

In 1066, saints relics and the oaths sworn over them really mattered. William summoned his vassals, formed a coalition with Brittany, Flanders and the French and gathered troops. Emissaries were despatched to Pope Alexander in Rome to elicit his support. With God on his side William could offer plunder and influence in a subjugated England while guaranteeing a place in Heaven for all that fell in battle. Even nature was allegedly disturbed by Harold’s wickedness. Halley’s Comet, `the terror of kings’ and a sinister portent of change appeared in the April skies over England. Harold was dismayed.

William gathered a vast army of about 8,000 troops at Divessur- Mer in the Seine Estuary. A fleet of 700 ships was assembled to transport his multi-ethnic invasion force of Normans, Bretons, Flemings and French with their war horses across the Channel. It was the largest amphibious operation to be mounted since Roman times. Up to 14,000 men it is assessed would have been needed in and around the muster area to support and conduct such an enterprise. They waited for much of the summer months for favourable southern winds that never came.

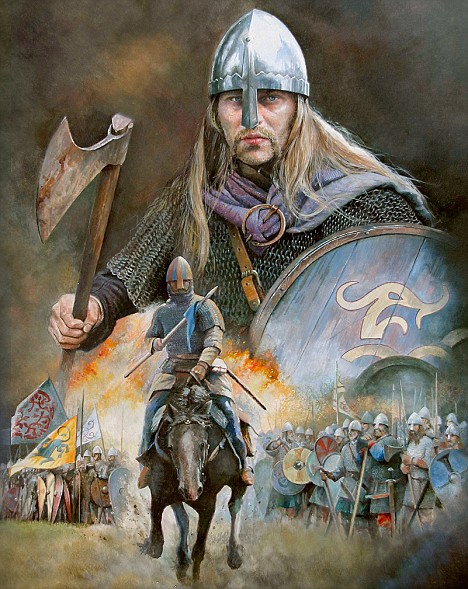

Harold assembled his forces and fleet on the home side of the Channel in anticipation of the Norman invasion, considered to be the immediate threat. The core of his army was an elite bodyguard of Housecarls and Thegns, bulked out by the Fyrd, the levee raised by the Anglo-Saxon mobilisation system. These men were obliged to perform military duty for two months in exchange for holding five hides of land and served alongside every able-bodied Freeman called out to defend his shire. With the pressure of harvest time and no sign of the Norman ships and the onset of unpredictable autumn weather Harold ran out of time. On the 8th September he disbanded the Fyrd and returned to London. Harald Hardrada unexpectedly struck first in the north, having crossed the North Sea in 300 longships. He joined Tostig with a smaller fleet in the Tyne and entered the Ouse River, raiding their way towards Riccal, ten miles from York. Harold’s northern earls were defeated at the Fulford Gate just outside the city. Having just disbanded his southern Fyrd Harold abruptly marched 190 miles north in five days with his Housecarls to summon the northern levee. On the 25th September he completely surprised and destroyed the Viking army at Stamford Bridge, killing Hardrada and Tostig in the process. Only 24 ships were left to ferry the battered Viking survivors back home after one of their worse reverses in England.

Two days after this momentous victory, William’s fleet crossed the Channel in the south. They had moved from Dives to Saint- Valery at the mouth of the Somme River and the fleet picked up the needed southerly breeze, which took them to Pevensey Bay. Unexpectedly the landings were not contested. The Normans built a wooden castle on the site of an abandoned Roman fort and moved ten miles east to Hastings, where they established another firm base protected by a second prefabricated wooden castle.

Harold likely received the shocking news at York on 1st October and counter-marched to London in only five days to repel a second major invasion inside two weeks. He rode ahead with his Housecarls, having to leave his archers and the northern Fyrd behind. The southern Fyrd had to be regenerated yet again. Having disbanded it only a month before, Harold was testing the Anglo-Saxon mobilisation system to its absolute limit.

By the evening of 13th October, Harold was mustering his new force just outside the Anderdswald Forest by the old hoar apple tree, a well-known landmark on Caldbec Hill seven miles north of Hastings. His core of Housecarls had marched 260 miles from York over a period of 12 days. The Normans had been harrying the villages around Hastings and the English would have smelt the locally burning villages as they assembled during the evening before battle. William sought to bring the unseen English army to a quick decision in battle.

Harold was striving to bottle the Normans up on the narrow causeway they had established for themselves surrounded by marsh and water around Hastings. He was astride the only route to London. Harold was not ready. His precipitate 58 mile, three-day forced march from London was intended to surprise William, like the Vikings at Stamford Bridge. William was, however, too wily and Norman scouts detected the English approach. Both sides numbered between 7,000 to 8,000 men. Harold’s force could well have been a half or a third bigger if he had paused. He was incensed at the ruthless Norman raiding, visited on his own property and people. After shattering the Vikings nearly three weeks before, he was convinced the Normans would follow suit.