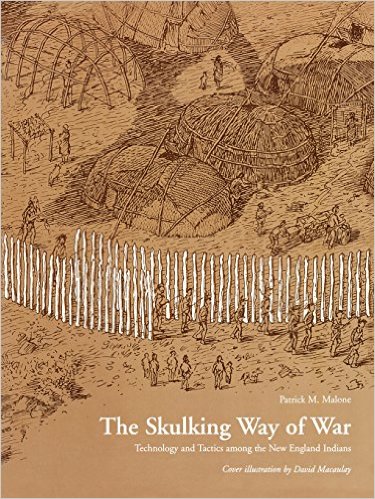

The Skulking Way of War: Technology and Tactics Among the New England Indians

by Patrick M. Malone (Author)

The stealthy native style of warfare practiced by Indians of the forest and lake country of northeastern North America. Skulking was essentially the mode of the natural guerilla and raider, with the cultural addition that forest Indians did not make a moral distinction between murder and “private war.” Thus, even in times that were otherwise peaceful, a young skulking brave might attack and kill personal enemies to hone his fighting skills and acquire honor and reputation. The “skulking way” as group combat was notable for avoiding direct assaults on heavy fortifications that would cost too many lives among attackers. Instead, it employed guile and ruses. It made effective use of ground and forest cover in making an approach, to spring ambushes, and for refuge in retreat or defeat. Skulking bewildered settlers, militia, and European regulars, at least until some of them-notably Canadian militia and, later, American rangers-learned its methods and began to use them in combat. Skulking enraged European officers, who viewed it as opposed to the “rules of war.” It should not have: Europeans themselves had for centuries “skulked” along wild frontiers in Ireland, Hungary, Scotland, and across the Militargrenze, waging petite guerre and guerre guerroyante from the borders of France and the Holy Roman Empire to Poland and Ukraine.

Well adapted to its environment as a military approach, the skulking way of war also reflected native cultural and ritualized religious values-some admirable, but others less so. At its core was the Indian brave, who was a warrior rather than a soldier. A brave was usually very young-training began no later than age twelve-exceptionally fit, and capable of greater speed and physical endurance on the march than his European allies, enemies, or prisoners. He was an expert marksman, taking the white man’s firearms, powder, and shot in exchange for furs and excelling in use of the rifle in hunting and war. As Armstrong Starkey has shrewdly noted, the brave possessed “the skills and discipline of modern commandos and special forces.” He could move and survive in winter by using snowshoes and eating scraps from the forest floor, while white troops stayed huddled in wooden huts, awaiting the spring, or died starving and frozen in the deep snow. In summer, he moved over river and lake in stealthy birchbark canoes that gave his war party unparalleled mobility and tactical surprise. His officers were “elected” on the basis of demonstrated bravery, audacity, and cunning, not mounted stiffly in a saddle by accident of birth, or from a purchased commission.

Indian military discipline was based on personal honor, rather than hard punishment. Indian tactics aimed at victory achieved with minimal loss of the lives of attackers. Tactical retreat, or refusing to fight in the face of superior numbers or fortified works, was thus commonplace. This infuriated European commanders, who misunderstood Indian battlefield prudence as cowardice or fecklessness toward the “cause,” further misreading the fact that Indians fought in white men’s wars for reasons of their own. A brave’s ethics were also akin to a modern commando’s, notably when it came to prisoners. They would take prisoners if chance permitted, or they would slaughter all their enemies because they could not move quickly with old men and women and children in tow. While contemptuous of enemy males who surrendered, a warrior could still treat a prisoner gently and adopt him (or her) into his nation. Or he might slowly torture or burn him (or her) to death. Unlike European or Asian soldiers for whom rape was a ubiquitous part of war, out of mystical taboo Indian warriors rarely molested captive women. In sum, braves could be as kind and humane or as callous and cruel as any other soldier, in any era.

Most eastern Indians quickly adapted to firearms, exclusively matchlock weapons prior to 1660 and principally flintlock firearms after that. Starkey argues that they abandoned bows and arrows because the ability of most braves to dodge arrows became an impossible feat with bullets. In short, Indians appreciated the greater hitting power of firearms. They often loaded weapons with several balls or bullets to maximize a gun’s wounding or killing effect. Moreover, Indians much preferred rifles to muskets for hunting and in war, domains they did not always distinguish. Most became expert riflemen well beyond the skills exhibited by settlers, who were mainly farmers who occasionally supplemented their winter larder with wild game. European regulars sported smoothbore muskets and fired in volley, were not trained in marksmanship, and did not aim at individual targets. Braves fired, moved to new cover to reload, fired again, and then moved again. This emphasis on aimed fire did not mean that they fought merely as individuals. War parties made up of larger numbers of braves, each firing and seeking new cover, conducted skilled advances and retreats “blackbird fashion.” In that style of fighting, braves with loaded guns covered those reloading or moving, rather as a modern commando unit in urban warfare moves from cover to cover under suppressing fire. The skulking way of war also reduced casualties, a great concern of Indian societies once demographic decline set in after contact with virgin European and African diseases borne by settlers or slaves.

Suggested Reading: Patrick Malone, The Skulking Way of War (1991); A. Starkey, European and Native American Warfare (1998).