Rommel

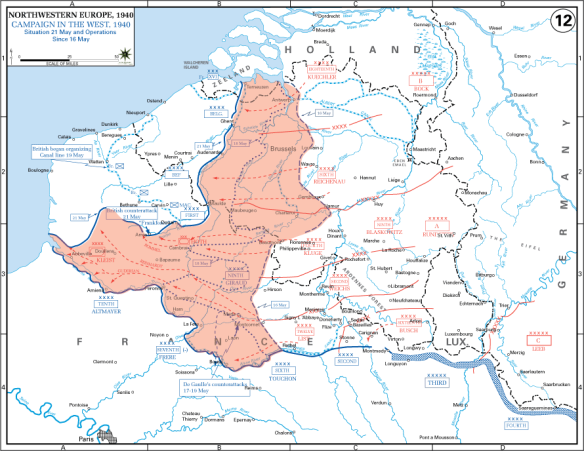

In the west, the Germans had sensibly seized bridgeheads across the Somme, when the Panzers had rushed westwards on 19 – 20 May. Guderian had ordered his men across the Somme at Abbeville before turning north to the Channel ports. Other bridgeheads were established south of Amiens and south of Péronne. All French attempts to destroy these jumping-off points in late May, using the newly assembled forces south of the river, failed. As fast as the French could transfer forces from the Maginot Line to create the new 10th and 7th Armies, the slow-moving German infantry marched up behind the Panzers to hold the Panzers’ gains. The presence and survival of these bridgeheads led von Bock to use his three new Panzer corps to break out. One was allotted to each bridgehead. It was assumed that what had worked in more difficult circumstances on the Meuse would work now, where no river had to be crossed in the face of hostile forces. Once again the attack would follow a massive softening up operation by the Luftwaffe. The screaming Stukas would surely intimidate the French as they had at Sedan. They didn’t. The French stood and fought and the old 75s took a terrible toll of the Panzers. The new strategy seemed to be working. The French Army group commander, General Besson, sent an optimistic report in the early afternoon that the French were holding the attack and inflicting heavy casualties. Kleist’s two Panzer corps made hardly any progress south of Amiens and Péronne. In the west, Rommel and Hoth’s Corps became bogged down in heavy fighting in the marshes of the lower Somme at Hangest and Le Quesnoy. This appeared a return to the chopping war of attrition that had marked the First World War. Colonel General List of the Twelfth Army commented:

The French are putting up strong opposition. No signs of demoralisation are evident anywhere. We are seeing a new French way of fighting.

The letter of a French tank officer to his wife makes the same point and totally contradicts the received opinion of French morale and fighting spirit:

We’ve taken a heck of a pasting, and there’s hardly anyone left, but those still here have fantastic morale […] we no longer think about the awful nightmare we’ve been through. That’s typical of the French soldier, if you could only know the happiness of going into a scrap with chaps like these.

The day’s fighting produced renewed confidence among both troops and politicians. It was just the psychological boost that Rundstedt had so feared in the first phase. Now it came too late. No amount of raised morale could counter the material shortages of the French Army.

On the 6th, the Péronne and Amiens bridgeheads continued to be contained and in three days the 10th Panzer Division lost two-thirds of its tanks in trying to break out south of Amiens, but once again it was Rommel who achieved breakout. After fierce fighting he reached 20 miles south of the Somme, cutting off the British 51st Division and a French unit from the rest of Altmeyer’s Tenth Army. On the eastern flank, along the infamous Chemin Des Dames – scene of so much fighting in 1914 – 1918 – the German infantry of their Ninth Army pushed the French back to the south side of the Aisne. On the 7th Rommel pushed on another 17 miles to Forges-les-Eaux. He had simply decided to ignore the ‘Hedgehogs’ and sweep round them across country. These were the stormtrooper tactics of 1918 applied to tank warfare. He was 25 miles from Rouen. Attempts at counter-attack failed – the French mobile reserves were too weak. The next day Rommel pressed on to Elboeuf on the Seine. The other Panzer division of Hoth’s Corps, the 5th, made for Rouen, which it captured. Manstein’s infantry corps had pressed on rapidly behind the tanks to increase the width of the breakthrough and reached the Seine by the 10th. Weygand recognised by the 8th that this second, less well-known Battle of the Somme was lost. Both flanks had been turned and he ordered a withdrawal. The Germans, anxious to exploit success, transferred Kleist’s battered corps eastwards to exploit the breakthrough on the Aisne. Once again German staffwork showed flexibility and skill.

Guderian

At 5am the eastern half of the battle began, but because there were no convenient bridgeheads as jumping-off points, Rundstedt ordered his infantry to cross the river first, to prepare the way for Guderian’s Panzers. As on the Somme, the French fought heroically. General Lattre de Tassigny, in command of the formidable 14th Division, threw the Germans back south of Rethel and took 800 prisoners. Guderian found himself unable to move and was embarrassed by a visit by his superior, General List, who found the Panzer troops relaxing – and even some bathing in a nearby stream – while waiting for the chance to move. Uncharacteristically immobile, Hurrying Heinz had to explain that it was not his task to establish a bridgehead. A small bridgehead had actually been established at Château Porcien to the west of Rethel, and under cover of darkness Guderian decided to pass the 1st Panzer Division across and then the 2nd. The result was a breakthrough to the south and on the 10th a hard-fought tank battle with elements of the remaining French mobile reserve. The quality of the French tanks was clear from Guderian’s description of the battle, but the French 3rd Armoured had few left:

A tank battle developed to the south of Juniville, which lasted for some two hours before being eventually decided in our favour. In the course of the afternoon Juniville itself was taken. There Balck managed personally to capture the colours of a French regiment […] While the battle was in progress I attempted, in vain, to destroy a Char B with a captured 47mm anti-tank gun; all the shells I fired at it simply bounced harmlessly off its thick armour. Our 37mm and 20mm guns were equally ineffective against this adversary. As a result, we inevitably suffered sadly heavy casualties.

The German infantry, with heavy artillery support, ground down the French ‘Hedgehogs’ and with too few mobile forces to counter the Panzers, the front was broken. Despite local successes the French tanks were simply too few to turn the scale of the battle. Heinz could once again hurry, rushing almost unopposed through the French countryside. The 2nd Panzer Division reached the outskirts of Rheims on the 10th. Now Kleist’s reallocated Panzers could join the chase, pushing down to the Marne, east of Paris.

By the evening of the 10th, the Germans were to the west of Paris on the lower Seine and to the east of the capital on the Marne. The French Government decided to abandon Paris for Tours on the Loire. This was devastating. In 1914, as the Germans reached the Marne and threatened Paris, the French had counter-attacked and saved France. There could be no counter-attack this time. The French writer, André Maurois, wrote of the significance of the decision:

At that moment I knew everything was over. France deprived of Paris, would become a body without a head. The war had been lost.

That same day Italy declared war. France would now face over thirty Italian divisions on her south-eastern frontier.

11 – 14 June 1940: The Briare Conference and the Fall of Paris

Military Headquarters had been pulled back to the town of Briare on the Upper Loire on 9 June. This, it was hoped, was sufficiently far south to be safe from marauding Panzers. The building contained a single telephone and, totally dependent on the local exchange, was non-operative for one hour in the middle of the day while the lady operator took her lunch. It was to this auspicious venue that the great and the good of the Allies repaired on the 11th, for a major review of strategy. Monsieur Reynaud, the French Premier, was accompanied by Marshal Pétain, his deputy, General Weygand and the recently appointed de Gaulle. Churchill arrived with the Foreign Secretary, Anthony Eden, General Ismay, Secretary of the War Cabinet and General Spears, Liaison Officer with the French Government. The conference began at 7pm with a lengthy and wholly pessimistic report from Weygand. Churchill urged a street-by-street defence of Paris to sap the strength of the Germans. Pétain made it quite clear that this was not going to happen. The French capital would not be reduced to rubble to hold up the Germans for a few days. There were repeated demands on Churchill for more air support, which he consistently refused. Weygand stressed that now was the decisive moment. Churchill, already anticipating what was to come, argued that it would be when the Luftwaffe was thrown against Britain. Weygand mentioned that France might have to ask for an armistice and the divisions in the French leadership were exposed when Reynaud snapped that this was a political matter. Despite Reynaud’s hostility, he was under real pressure from Pétain to seek peace, as he later told Churchill. With nothing settled, the British Prime Minister and his entourage left after a brief meeting the following morning. He had arrived with an escort of twelve Hurricanes but cloud prevented their presence for the return. Assured that it was likely to be cloudy all the way to London, Churchill decided to return without escort. The history of the twentieth century could have been very different if two Luftwaffe pilots had been more alert. The cloud cleared as Churchill’s plane reached the coast. Two German pilots were too busy firing at fishing boats to see the flamingo transport and its precious cargo. Churchill reached Hendon Airport unscathed. Would Britain have continued fighting without him? The risk of such flights had no deterrent effect and he returned the next day for further talks with Reynaud at Tours. Little was accomplished: it would be four years before Churchill set foot in France again.

On the day that Churchill arrived at Briare to plead for a bitter defence of Paris, the French Government declared it an open city and by the 13th the last French troops had left. German forces were already close to the outskirts. Next morning a lieutenant-colonel, Dr Hans Speidel, took the surrender of the city and German infantry of the 87th Division moved in peacefully. Rifles and Spandau machine guns were quickly put aside for cameras. The warriors were transformed into tourists.

To the west of Paris, Rommel continued to garner more military laurels. His forces swung north-west from the Seine towards the isolated elements of the Tenth Army in and around St Valery-en-Caux on the coast. The cut-off British and French forces had retreated there in the hope of evacuation. The site was unsuitable and following the orders of his superior French corps commander, General Fortune felt obliged to surrender himself and the whole of his 51st Highland Division to captivity on 12 June. To the east of Paris, Guderian’s Panzers reached Chalons sur Marne by the 12th. His advance southeastwards threatened to cut off the vast numbers of French troops on the frontier and manning the Maginot Line. The French commander, General Pretelat, had already made two requests to Weygand for permission to make plans for withdrawal. Weygand refused until the 12th. It was too late and Pretelat only began the essential strategic retreat on the 14th. By this time Guderian’s forces had rushed towards the south and east, cutting off any such retreat. Guderian, in his memoirs, paints a picture of a headlong dash, with infantry units jostling Panzers to get at the enemy and press further into France. Once again the indestructible Balck makes an appearance. Guderian came upon him by the Rhine – Marne Canal. Asked if he had secured a bridgehead, Balck rather hesitatingly agreed that he had. Guderian discovered that in so doing Balck had disobeyed corps’ orders to halt at the canal. Here, again, is an illustration of the aggressive initiative shown by relatively junior officers in thrusting forward. Early on the 14th the 1st Panzer Division had reached St Dizier, taking considerable prisoners from the French 3rd Armoured, the 3rd North African and the 6th Colonial Divisions. In Guderian’s words: ‘they gave the impression of being utterly exhausted.’ By the early morning of the 15th, Langres had fallen with yet more prisoners. But even more disastrously for France, a further 400,000 French soldiers were now trapped in a vast pocket between Nancy and Belfort.

15 – 24 June 1940: Endgame and Armistice

By the 15th, the campaign was effectively decided. In the west Rommel was to set a new record for a daily advance. He covered 150 miles on 17 June and on the 19th took Cherbourg. During Case Red, as during Case Yellow, the achievements of his 7th Panzer Division had been remarkable, capturing 97,648 prisoners for the loss of 682 killed. In the same period, Guderian’s forces swept on to the Swiss frontier at Pontarlier by the 17th, and then swung north to the Maginot Line. It was clearly over for the French Army, which secured an armistice with Germany on the 22nd.

The final defeat of France involved a second British evacuation from France, south of the Somme. There were considerable numbers of British forces, both fighting units – like the 1st Armoured Division – and line of communication troops. Churchill initially hoped to build up a new BEF of four divisions, using the Canadians and the 52nd Lowland Division. There were dreams, even as the scale of the French collapse became apparent, of creating a stronghold or redoubt in Brittany, from which the Germans could be defied. To command this new BEF, Brooke was sent back, strongly suspecting that the whole episode was a futile gesture. Knighted at Buckingham Palace on the 11th, he was in Cherbourg by the evening of the 12th, the day that one of his divisions, the 51st Highland, had been forced to surrender to Rommel on the Normandy coast. Brooke went to see both Weygand and Georges and their attitudes confirmed his sense of futility. They made it clear there were not enough troops to establish a defensive perimeter in Brittany. On the 14th he decided British troops should be withdrawn – the newly arrived Canadians to leave from Brest and the 52nd to retire to Cherbourg. Others were dispatched to Nantes for embarkation. Brooke had a difficult time convincing Churchill when a telephone link was established with 10 Downing Street, and he was heard to say: ‘You’ve lost one Scottish Division. Do you want to lose another?’ In his diary he confesses to being repeatedly on the verge of losing his temper. Churchill told him that he had been sent to make the French feel that Britain was supporting them: ‘I replied that it was impossible to make a corpse feel.’ In the end Churchill agreed.

Brooke succeeded in evacuating the vast bulk of British forces still in France. A total of 144,171 British troops were taken off, in addition to several thousand allies, including nearly 25,000 Polish troops. In addition, 300 guns were successfully withdrawn for future use. Nearly 60,000 left from Nantes/St Nazaire, which was to be the scene of the outstanding disaster of this second and little-known withdrawal. Here the liner Lancastria was hit by bombs on the afternoon of the 17th. Although nearly 2,500 were rescued over 3,000 were drowned. It was so disastrous, news was kept from the public. Brooke himself left St Nazaire next day on a trawler, reaching Plymouth on the 19th. He had been right about the French inability to continue the struggle.

Reynaud had lost the political struggle with Pétain and on the 16th resigned. Churchill had offered an indissoluble union of the two countries but the French Cabinet rejected it out of hand. Pétain likened it to union with a corpse – coming from the octogenarian marshal, who was himself described as a wheezing skeleton, this was possibly a simile too far. Weygand, Pétain and a majority of the leading figures in the Third Republic, felt that Britain was finished and the thought of abandoning metropolitan France to continue the war in North Africa quite unacceptable. As one of them said, France would become another British Dominion. Not all agreed and Brigadier de Gaulle took off for London in the plane carrying Sir Edward Spears home, his liaison mission over. However, to most of France’s military and political leaders, it seemed better to seek accommodation with the new ruler of Europe. Pétain replaced Reynaud and the next day sought an armistice through the good offices of Spain. On the same day, the 17th, he broadcast to the French people that the fighting must stop, and the words of the old relic of World War One sapped the will to resist in many units – but not all. The officer cadets at Saumer held the bridges over the Loire for two days till their ammunition ran out.

Italy had thirty-two divisions on the Alpine Front. Mussolini had delayed his declaration of war till it appeared that France was defeated and to delay longer risked exclusion from potential spoils. Facing the Italians was a small French force of three B class divisions, like those that had received the brunt of the German attacks at Sedan, plus three fortress divisions. This tiny Army of the Alps was thus outnumbered five-to-one. It had, however, the advantage of the rugged Alpine terrain and a competent commander, General Olry, who had prepared his positions well, with carefully chosen positions for his artillery and excellent observation posts. In addition, plans had been prepared to block the narrow Alpine passes, massively increasing the Italian logistic problems. The Italians may have declared war on the 10th but there was no offensive activity until the 20th, when the Germans had reached the Rhône Valley and threatened Olry’s force from the rear. The attacks on the Mont Genevre Pass were blocked, as were almost all others. Despite small successes, on the 21st and 22nd, when the armistice came into force on the 24th, the French had barred the Italian advance from Switzerland to the coast. French B divisions, when well lead and prepared, could fight well and effectively.