Between 58 and 53 B. C. Julius Caesar’s conquest of Gaul had dealt successively with the east, north, and west of Gaul, but the center had remained virtually unscathed, especially the Massif Central, the homeland of the Arverni, the most powerful tribe in Gaul in the second century B. C. and still a major force in the first century. Among the Arverni, the leader of the anti-Roman group was a young noble, Vercingetorix, who attempted a coup d’état during the winter of 53-52 B. C. but was expelled from the main town, Gergovia. The setback was short-lived; Gergovia was quickly back in Vercingetorix’s hands, and he started building a coalition with the neighboring tribal states to oppose Rome.

Caesar was in northern Italy, but he moved swiftly to combat any attack on the Roman province of Transalpine Gaul. He raised an army and, despite the fact that it was winter, crossed the Cevennes into the Auvergne. He moved on to gather his legions, which were in winter quarters around Agedincum (Sens). With these forces he was able to take the offensive, capturing the oppida (defended towns) of Vellaunodunum (Chateau-Landon), Cenabum (Orléans), and Avaricum (Bourges). Sending four legions north under Labienus against the Parisii, Caesar returned with the remaining six to attack Gergovia. Vercingetorix had arrived before him and had installed his troops in and around the oppidum.

Caesar describes the town as lying on a high, steep-sided hill, easily accessible only by a col (narrow neck of land joining two pieces of high ground) on the western side. The town was surrounded by a wall, with a second stone wall 2 meters high halfway up the slope; the Gallic forces were camped on the slopes, with garrisons on the neighboring hills. Caesar captured a poorly defended hill at the foot of the town and constructed his “large camp”; he subsequently captured a second hill “facing” the town, on which he built the “small camp,” linked with the large one by a double ditch, or “duplex” (Caesar’s use of the word “duplex” has been interpreted by some scholars to mean two parallel ditches separated by a pathway, and by other scholars as two ditches on the side facing the enemy protecting the route). Rather than attempt a siege, Caesar launched an attack; though his troops overran the outer wall, attacked the gates, and even mounted the town wall, they were forced to retreat, the only defeat Caesar suffered in the field. It led to a general revolt among the Gauls, and but for a tactical mistake by Vercingetorix, leading to the siege at Alesia, the Romans might well have been forced to retreat from Gaul. The battle of Gergovia had almost changed the course of the history of the Western world.

#

Later La Tene Celts developed a number of specialized modes of combat. They continued the development of chariot and mounted warfare, becoming the most formidable cavalry Europe had yet seen. Their armies were highly mobile, and their two and four wheeled chariots (essenda) gave them the advantage over all but the most disciplined and well-armed infantry. Elite chariot burials have been found across Europe. By the time of Caesar’s conquest, chariots had gone out of fashion in combat on the Continent, but they were still so used in Britain.

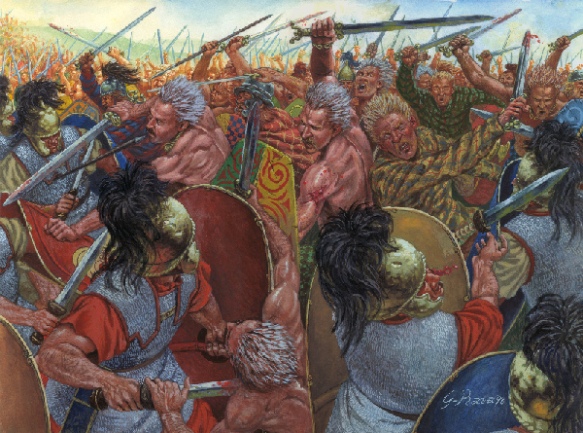

Celtic warriors employed a wide array of weapons: arrows, javelins, short- and long-bladed swords, and-in Iberia-the falcata, a heavy cleaver- like weapon that the Roman historian Livy claimed could sever a head or a limb in a single stroke. Slings were almost certainly used much earlier but the “ammo dumps” of sling stones found beside Late Bronze and Iron Age fortifications, such as Maiden Castle, are the first clear evidence of their use in Europe. Both mounted and chariot-borne troops utilized javelins. They would rapidly advance, release their missiles, then retire to safety. The Celtiberians of Spain used a short stabbing sword, the gladius, so effectively against the Romans that the latter adopted it as their legions’ principal weapon. Celtic warriors used long shields of an oblong or rectangular shape and wore horned or plumed metal helmets. A few of these have survived, although some were so fragile they were more theatrical than protective. Ornate “jockey cap” helmets with gold plating and coral inlays, such as the splendid fourth century B. C. examples from Amfreville and Agris, France, are known from the La Tene period.

The Celts’ best warriors, called gaesatae, wore torcs, thick-braided circlets of metal, around their necks. Gaesatae usually fought naked, sometimes with their bodies painted blue with dye made from woad (a type of herb), in the front ranks of Celtic armies. Because of their reputation for ferocity, they were hired as mercenaries into many Mediterranean armies. According to classical authors, the Celts preferred to settle conflicts in single combat between opposing leaders or champions. The long blunt-ended swords, useful only for slashing, that equipped most Celtic warriors reflected this predilection for single combat. Because of their longer reach, these were best in open, uncrowded combat, but unwieldy in crowded close quarters, as the closed ranks of Roman Legions with their stabbing swords would demonstrate in many battles.