This sort of fighting led to average gains of 1-3 miles per day, not much more than the range of a creeping barrage (showing how much the infantry wanted and needed support – which was understandable, with them fighting every day). Often the attack would peter out by midday, with the afternoon spent organising for the next day’s attack, scouting, laying telephone cable and bringing up supplies. With few tanks available and the ever variable weather limiting the RAF’s activities, artillery was the most reliable support for the infantry and the BEF recognised that artillery support reduced casualties. The senior gunner at GHQ reported: `All army commanders are at me not to reduce the artillery and say with the present state of the infantry they cannot do with a gun less…’.

Where the German defences were thicker, as at the Hindenburg Line, the BEF slowed down and brought up the panoply of trench-warfare tools. More guns and ammunition were sent forwards, and for the artillery the sound-ranging and flash-spotting sections also moved up. Survey units needed only 40 hours to identify friendly positions to a reasonable standard, allowing good (if not perfect) shooting in only two days. It helped that the BEF did not face the same challenges as in previous years: German morale was so much lower that there was no need to demolish the defences, only to crack a way in and let the infantry fight their way through, albeit with artillery support.

Rawlinson’s Fourth Army would be tackling the Hindenburg Line, and as his men reached it and drove in the outposts, they had an inestimable advantage: on 8 August they had captured a detailed map of the sector they would be attacking. It marked the locations of all the key German installations, so the British could select exactly what they needed to hit and not waste shells from their 1, 600 guns. The pinpoint targeting probably increased the demoralising effect on the German troops, who would have seen an uncannily accurate bombardment. As the British noted at the time, `Prisoners state that our 48 hours’ bombardment prior to the attack was extremely effective, and that it was owing to this that the pioneers of the 2nd Division were unable to blow up the bridges over the canal at Bellenglise, as they did not receive food for two days and dared not leave their dugouts owing to the artillery fire.’ Increasing the demoralisation was the first British use of mustard gas. The Germans had used it during the Third Battle of Ypres, but it took British industry roughly a year to identify the chemical, develop a production process and make a substantial quantity of shells. Now they were being used and were fired early so that the Germans would experience the worst effects. In theory (after the four-day bombardment), there would be little residual effect for the attacking British troops.

Mustard gas certainly helped the bombardment, but there were plenty of problems to counter-balance. The weather was mediocre, with rain and cloud producing a murk that seriously reduced observation (from air or ground) and affected the counter-battery effort. The Germans also moved guns around as best they could, given their serious shortage of horses, and the net result was that the German artillery was not particularly well suppressed. Ammunition supply was also a weak point for Rawlinson. Only one main railway line was in working order and the roads were clogged with units and vehicles. Shells could be brought up, but often arrived late. With other operations under way or in preparation (Foch had Belgian, British, French and American attacks scheduled for the end of September), there were simply not enough guns to go around, and the Fourth Army had fewer than they would have liked. But the bombardment still involved 750, 000 shells (including 32, 000 mustard gas ones) over four days, starting on 26 September. Counter-battery fire was vigorous, while wire-cutting was absolutely vital since there were few tanks available and much wire; harassing and interdicting fire were also important across the depth of the German position, and there were of course the machine-gun nests and dugouts to hammer.

Rawlinson was attacking the toughest point of the Hindenburg Line in two sectors: the Americans and Australians faced the Bellicourt Tunnel, which was heavily fortified because the tunnel was an obvious weak point, while IX Corps was planning to cross the St Quentin Canal, a formidable feature in itself (35 feet across and up to 50 feet below the natural level of the ground) with lots of barbed wire and a good number of machine-gun positions. However, IX Corps was attacking the Bellenglise Salient, and it was simple to concentrate shells on the salient and get advantageous angles of fire.

On the 29th there was fog (in addition to the smoke shells mixed into the barrage) which substantially bothered the Germans. Their artillery observers could not see what was happening and infantry could not see very far. This fog was bad for the RAF but it was still a net benefit for the attacking Allies because air support was only a modest benefit. One brigade commander wrote later: `The night 28/29 had been an unpleasant one – very dark and wet, everyone on the move, heavy shelling and much gas, and quite a number of casualties; but the morning found us merrily firing our barrage, which lasted several hours (3, 000 rounds by Zero + 512) and left us in the immediate necessity to bring up more ammunition.’

The attacks developed very differently. The US 27th Division attacked without a creeping barrage (because of fears that isolated groups of friendly infantry were still scattered around after a preliminary attack) and barely captured the German forward line. The 30th American Division did better, largely due to having better observation posts (so their preliminary bombardment had been more effective) and a creeping barrage for cover, but they pushed too hard without mopping up effectively. They punched through the German line but reserve troops got held up by the by-passed Germans and spent their strength mopping up and fending off the inevitable German counter-attacks. The American/Australian attack had pushed the Germans back and partly broken through, but hitting the Germans in this heavily fortified and defended sector had proven problematic.

Meanwhile IX Corps led its attack with the 46th (North Midland) Division crossing the canal. The terrain problems were formidable, but the bombardment had done much to help, for instance by knocking down sections of the brick walls to make it easier to get out of the canal. But the unit needed ladders to get down to the canal, boats to get across and ladders to climb back out. Good staff work provided all that and more, including life-jackets from cross-Channel steamers, to get more men across the canal quickly. On the 29th their careful planning was only part of the explanation for their success. The Germans were extremely surprised by the bold frontal attack, and that threw them off guard. Their reactions were also slowed by the fog. A heavy bombardment had played a role, with the men of the 46th covered by an exceptionally dense creeping barrage: no fewer than 54 18-pounders each firing two rounds per minute and 18 4. 5-inch howitzers each firing one round per minute covered the 500-yard bridge-head. The leading brigade cleared the German advanced positions, crossed the canal and reorganised; reserves crossed under a protective barrage and then turned laterally to widen the hole. When the fog cleared, the Germans were able to direct in more artillery fire, but thanks to the preliminary bombardment their communications were patchy and they simply lacked the strength. The corps’ reserve division moved through the hole and by the end of the day the corps had taken 5, 100 prisoners and 90 guns. It was a stunning accomplishment: the Main Hindenburg System and the Hindenburg support System had both been broken on a corps’ width, and the BEF had overwhelmed the Germans’ last prepared defensive line. It was made possible by a combination of good infantry training, effective artillery preparation and support, and intelligent leadership. As Charles Budworth, the Fourth Army’s senior artilleryman, boasted in his report, `The results of our artillery fire as a death-dealer and as a life-saver are written on the ground and in the trenches by German corpses and unused rifles and ammunition.’

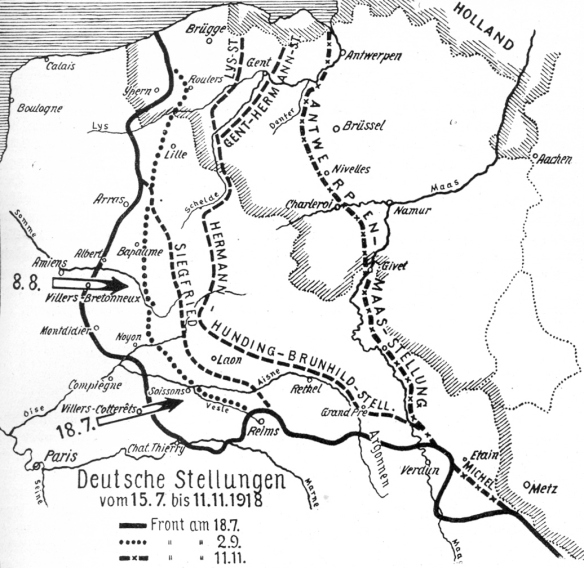

Bad news was pouring in to Hindenburg, Ludendorff and the Kaiser. The Turks had been routed in Palestine; the Bulgarians were breaking under attack around Salonika; repeated Allied attacks were hitting the Western Front. Their last hope had been to fall back to a winter defensive line and hope the Allies exhausted themselves in fruitless attacks, but now all they could do was retreat as slowly as possible and hope to gain better terms as armistice negotiations began. Ludendorff continued trying to tweak tactics to win, possibly trying to avoid thinking about the collapsing strategic position. The same day that Rawlinson broke through the Hindenburg Line and the Salonika front collapsed, Ludendorff was sending out new instructions: `The selection of a position is dependent on artillery observation, by which the ground in front of and behind the main line of resistance must be watched. This generally entails a reverse slope position. The possession of high ground is not of so great importance for the infantry defence.’ Moreover, artillery machine guns were to be integrated into the overall checkerboard of resistance and `the guns will fight to the last, their fire over open sights forms an extraordinarily effective support to the infantry’. He was at least realising that Allied attacks were routinely reaching the artillery positions, but paper instructions from the First Quartermaster General could not make the German artillerymen fight to the last: Germany was defeated.