One of the last battles of the Peninsular War, fought between the French under Marshal Nicolas Soult and the Anglo-Allies under the Marquis of Wellington.

On the morning of 23 February 1814 the left wing of the Allied army under Lieutenant General Sir John Hope began its daring but hazardous crossing of the Adour to the west of Orthez. The Coldstream and 3rd Foot Guards, supported by riflemen of the 5/60th (5th battalion, 60th Regiment), crossed the river in small groups, each party being ferried across the river in small rafts. By the end of the day a bridgehead had been established, and even a French counterattack failed to stop the operation when a battery of rockets was scattered among them, sending the startled Frenchmen running for cover. By the afternoon of 26 February a bridge of boats had been constructed across the river, which enabled Hope to get some 8,000 men across to the north bank. Bayonne was now completely surrounded, and the blockade of the town began.

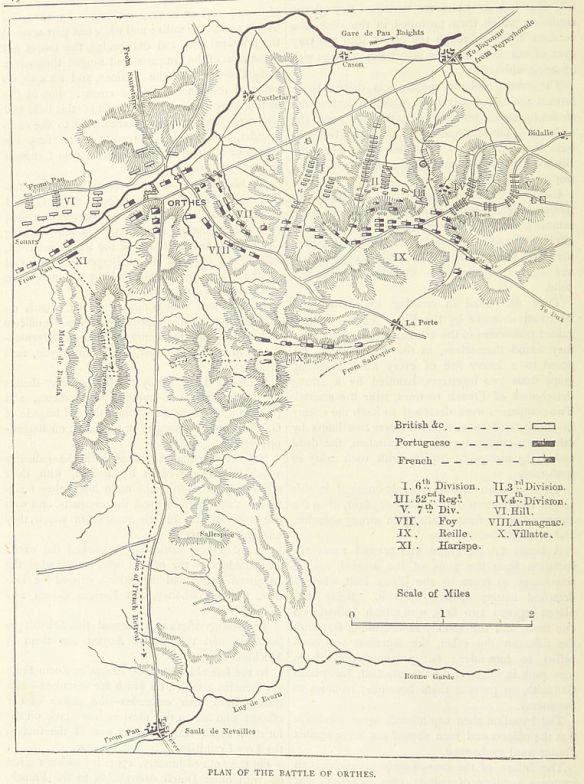

The day after Hope’s blockade began, Wellington, with the main Allied field army, fought a major battle at Orthez, some 35 miles away to the east. On 26 February Beresford had crossed the Gave de Pau with the 4th and 7th Divisions near Peyrehorade, pushing Soult back toward Orthez. The 3rd Division forded the river at Berenx, while Wellington himself brought up the 6th and Light Division, plus a force of cavalry, across on a pontoon bridge that had been thrown across the Gave, also at Berenx. Lieutenant General Sir Rowland Hill, meanwhile, with the 2nd Division and Carlos Le Cor’s Portuguese division, marched to the south of Orthez, passing to the east of the town but remaining on the south bank of the Gave.

On the morning of 27 February Wellington had with him on the northern bank of the Gave some 38,000 infantry and 3,300 cavalry, as well as 54 guns. Soult’s army, about 7,000 fewer with 48 guns, occupied a strong position along a ridge that ran north from Orthez for about a mile before running west for 3 miles from the bend in the main Bayonne-Orthez road, which ran along the ridge, to the small village of St. Boes, upon which Soult rested his right flank. Soult’s troops occupied the whole length of this ridge from which three very prominent spurs extended south toward the Gave. The spur on the extreme western edge of the ridge does not actually connect with the ridge itself, being separated by a few hundred yards. The remains of an old Roman camp were situated on the forward edge of the spur and would feature prominently in the battle.

The battle opened shortly after 8:30 A. M. on the cold, frosty morning of 27 February, when a battalion of French infantry was driven from the church and churchyard of St. Boes by the 1/7th, 1/20th, and 1/23rd, who made up Major General Robert Ross’s brigade of the 4th Division. The brigade advanced east along the ridge to clear the rest of the village, but it came under fire from French artillery and could go no farther. French troops under General Eloi, baron Taupin were then sent to recover the village, and St. Boes became the scene of bloody house-to-house fighting as both sides struggled for its possession.

While the fight for St. Boes flickered and flared, Lieutenant General Sir Thomas Picton’s 3rd Division entered the fray, attacking Soult’s center. His troops advanced up the two center spurs but were held up by French artillery that swept the crests of the spurs, inflicting heavy casualties. The attack here was only intended to be a demonstration, however, and he pulled his troops back, leaving just his strong skirmishing line of light troops and riflemen to prod and probe the French line, which they continued to do for the next two hours.

Meanwhile, the fighting in St. Boes intensified until at about 11:30 A. M. Wellington gave orders for an assault along the whole length of his line, leaving part of the Light Division only in reserve at the Roman camp, from where Wellington watched the progress of the fight.

On the Allied left, Major General Thomas Brisbane’s brigade of the 3rd Division began to push its way up the easternmost spur, with the 6th Division following behind. At St. Boes the 4th Division was replaced by the 7th Division, while the 1/52nd advanced from the Roman camp to deliver an attack on the French brigade on the right flank of the advancing 7th Division.

These attacks were pressed home vigorously, but French resistance was stiff, and it was to take the advancing British columns about two hours of hard fighting to drive the French from the spurs. This was not accomplished without loss, particularly to the 1/88th, three companies of which suffered heavy casualties when a squadron of French cavalry, the 21st Chasseurs, charged and overran them after catching them in line. The French cavalry suffered similarly when they received return fire from Picton’s men, half of their number being killed or wounded.

The French troops along the ridge were being severely pushed by Wellington’s attacking columns, but it was the advance by the 1/52nd, under Lieutenant General Sir John Colborne, that decided the day. This battalion entered the fight in support of Walker’s 7th Division just at the moment when this division, along with Major General George Anson’s brigade of the 4th Division, was finally driving the French from the body-choked village of St. Boes. The 52nd advanced almost knee-deep in mud in places, but when it reached the crest of the spur it took Taupin’s division in its left flank. Taupin’s men were driven back by Colborne’s determined charge and fell in with those retreating from St. Boes. In so doing, they precipitated a degree of panic, which caused the collapse of the entire French right. It was now about 2:30 P. M., and with Wellington’s triumphant troops pouring along the main road on top of the ridge the day was as good as won.

At first, Soult’s army began to fall back in an orderly manner with the divisions of generals Eugene Casimir Villatte, comte Villatte, and Jean-Isidore Harispe, comte Harispe drawn up on his left flank to cover the withdrawal. However, Hill’s corps had crossed the Gave to the east of Orthez and fell upon Harispe’s division, driving it back upon Villatte. The controlled retreat soon became a panic-stricken flight, which spread along the whole of the French line, Soult’s men discarding great loads of equipment to facilitate their retreat to the northeast toward Toulouse.

The Battle of Orthez cost Wellington 2,164 casualties, while Soult’s losses were estimated at around 4,000, including 1,350 prisoners, a number that would have been far greater had not Wellington been slightly wounded toward the end of the battle. This had caused him to halt and incapacitated him during the next few days. The wound was his third of the war, but at least he could rest that night with the satisfaction of knowing that there was little now standing between himself and final victory over the French.

References and further reading Beatson, F. C. 1925. Wellington: Crossing the Gaves and the Battle of Orthez. London: Heath, Cranton Limited. Esdaile, Charles. 2003. The Peninsular War: A New History. London: Palgrave Macmillan. Gates, David. 2001. The Spanish Ulcer: A History of the Peninsular War. New York: Da Capo. Glover, Michael. 2001. The Peninsular War, 1807-1814: A Concise Military History. London: Penguin. Napier, W. F. P. 1992. A History of the War in the Peninsula. 6 vols. London: Constable. (Orig. pub. 1828.) Oman, Sir Charles. 2005. A History of the Peninsular War. 7 vols. London: Greenhill. (Orig. pub. 1902-1930.) Paget, Julian. 1992. Wellington’s Peninsular War: Battles and Battlefields. London: Cooper. Robertson, Ian. 2003. Wellington Invades France: The Final Phase of the Peninsular War, 1813-1814. London: Greenhill. Uffindell, Andrew. 2003. The National Army Museum Book ofWellington’s Armies: Britain’s Triumphant Campaigns in the Peninsula and at Waterloo, 1808-1815. London: Sedgwick and Jackson. Weller, Jac. 1992. Wellington in the Peninsula. London: Greenhill.