In the half century after the death of Emperor Alexander Severus, the Roman Empire entered into a period of administrative chaos. There were scores of claimants to the imperial throne, and some ruled (and survived) for only a few months. At the same time, invaders began to penetrate the borders of the empire-Goths threatened the north and Persians the east. In the course of this chaos, Palmyra, a small client kingdom on the eastern edge of the Roman Empire between Rome and Persia, rose to prominence.

Palmyra was a wealthy city that lay on the caravan routes between Phoenicia, Syria, and Egypt. Lists of commercial taxes show that goods came all the way from China and India through the hands of merchant aristocrats. In this cosmopolitan city, people spoke Latin, Greek, Aramaic, and Egyptian, and since the second century A. D., some of its illustrious citizens had risen in the ranks of Rome. One such successful man was Odenathus, whose grandfather had been a Roman senator in about A. D. 230 and who had become a Roman consul himself in A. D. 258. Events and the breakdown of central authority brought Odenathus even more prominence.

In A. D. 260, the Roman emperor Valerian was defeated and held captive by the king of Persia. Odenathus took to the field with archers and spearmen of Palmyra and the cavalry of the desert Arabs, and he defeated the Persian forces. According to one chronicler, they even captured the magnificent treasure of the Persian emperor. A year later, Odenathus scored another victory against a Roman general in Syria who had set himself up as emperor. The new legitimate emperor, Gallienus, gave Odenathus the title of king in Palymra and created an alliance with him to help secure the eastern borders. Odenathus enjoyed his title for only a few years, however, for in about A. D. 266, he was assassinated. In the same attack, Odenathus’s heir was also killed. Then his second wife, Zenobia, took power, ostensibly serving as regent on behalf of her own young son. Zenobia’s accomplishments eclipsed those of her husband, and she captured the imagination of ancient and modern historians.

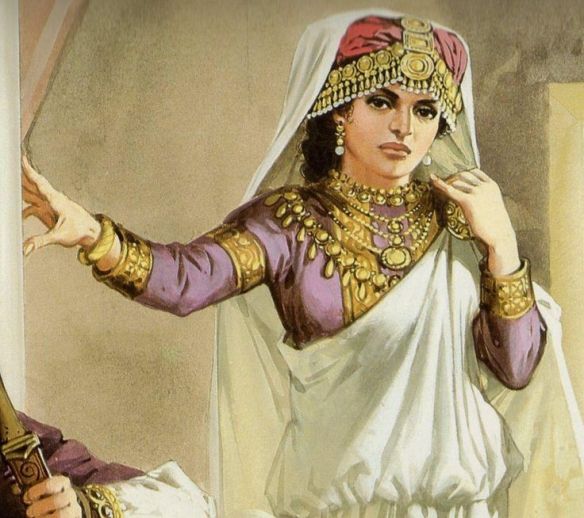

A collection of Roman biographies written in the fourth century A. D. (called the Scriptores Historiae Augustae) included an account of Zenobia’s life. The authors praised her beauty, calling her “the noblest of all the women of the East” and “the most beautiful” (Fraser 114), with black eyes and dark skin and teeth so white that many believed she wore pearls in her mouth. These historians also attributed to her a measure of chastity, claiming that she only allowed her husband in her bed in order to conceive her sons and did not permit him near her at other times. There is no evidence to corroborate that story, and she did bear three sons. Zenobia claimed that she was descended from the famous Egyptian queen Cleopatra VII, and she seems to have planned to claim the same power as that famous queen. She certainly had the same ambition.

Once Odenathus was dead, Zenobia quickly took control and was not content to hold Palmyra; she began to expand at the expense of the beleaguered Romans. By A. D. 269, her general Zabdas had secured most of Egypt, and at the same time Zenobia had annexed most of Syria. A year later, Zenobia conquered as far north as the Black Sea. Palmyra was now a respectable empire in its own right, and more importantly, it controlled much of the commerce that was so vital to Rome. To add a final insult, Zenobia took a step her husband had not-she declared herself formally independent of Rome. Confirming this independence, Zenobia called herself empress, and in A. D. 271, she had coins struck on behalf of herself and her son. Rome did not let this insult go unanswered.

In the midst of its chaos, Rome acquired an emperor-Aurelian (r. A. D. 270-275)-whose military skill restored most of the lands that were falling away from the empire. He first reconquered Egypt, and then marched north, slowly retaking the lands that Zenobia had claimed as her own. Zenobia led her army against Aurelian, riding her horse in the thick of battle while transmitting orders through her generals. The Palmyran cavalry lacked the discipline of the Roman legions and were lured into a horrible slaughter. Zenobia escaped across the desert to her home city of Palmyra, but Aurelian pursued her and besieged the city.

During this time, Aurelian and Zenobia were said to have exchanged correspondence. Aurelian asked her to surrender, writing “How, O Zenobia, have you dared to insult Roman emperors?” (Fraser 123). Zenobia reputedly responded with defiance worthy of Queen Cleopatra. Zenobia then was going to seek help from the Persians and planned to escape the siege of Palmyra by fleeing on a female camel, which was supposed to be faster than the fleetest horse. She escaped the city and made it as far as the Euphrates River, where she was captured as she was boarding a boat-she was either recognized or betrayed. She was brought before Emperor Aurelian as a captive and was unable to do anything to save her city, which was captured and sacked.

At this point, Zenobia’s instinct for survival overrode her pride. She claimed that she was a “simple woman” who had been led astray by her advisers. She even renounced the bold letter that she had sent to Aurelian, claiming it had been written by someone else (although another scholar swore that Zenobia herself had dictated it to him). These claims earned her some clemency, for Zenobia was taken to Rome as a captive. She was forced to march in Aurelian’s triumph, during which she walked shackled by golden chains and weighed down by the heavy jewels that she had once worn so proudly.

Perhaps remarkably, Zenobia’s career did not end in chains. At some point, the Roman state allowed her to retire in affluence to a villa near Tivoli. She married a Roman senator and had more children. At the same time, she entertained lavishly in Rome, and the only scandal that remained attached to her was that she spoke Latin with an outlandish accent. Her command of Greek, Aramaic, and Egyptian, however, made her an exotic hostess.

Aurelian had to return to Palymra again to put down another rebellion, and this time he sacked the city so thoroughly that the distinctive Palmyran civilization disappeared. Zenobia, however, continued to thrive in Rome, a testament not only to a bold warrior-queen but to a survivor who could find some victory even in military defeat.

Suggested Readings Balsdon, J. P. V. D. Roman Women: Their History and Habits. New York: John Day, 1963. Fraser, Antonia. The Warrior Queens. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1989. “Historia Augusta.” In Scriptores Historiae Augustae. Trans. D. Magie. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1967.