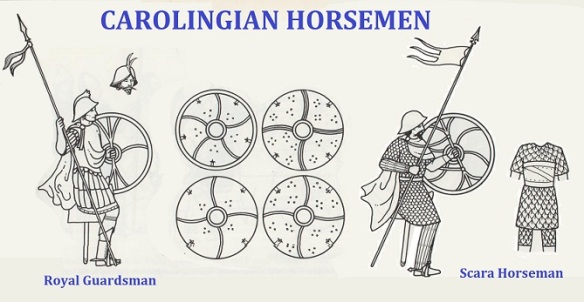

FRANKS – Scola Heavy Cavalry and Scara Bodyguards

8th Century Frank Scara

Pepin II of Herstal

Important battle in the rise of the Carolingian dynasty that helped secure the place of the Carolingians in Austrasia and the Frankish kingdom as a whole. Although a decisive victory for Pippin II of Herstal, it was not the decisive turning point in Carolingian history that it is often made out to be. The battle did strengthen Pippin’s position as mayor of the palace, but it was two generations before another Carolingian, Pippin III the Short, claimed the kingship of the Franks.

During the seventh century, as the fortunes of the Merovingian dynasty declined and the kingdom was once again divided among the later descendants of the first great Merovingian king, Clovis (r. 481–511), into the regions of Austrasia, Neustria, and Burgundy, rival aristocratic factions competed for power against each other and against the Merovingian do-nothing kings (rois fainéants), as they have traditionally been called. In the region of Austrasia the descendants of Arnulf of Metz, the sainted bishop and ancestor of the family, had once again taken control of the office of mayor of the palace. In Neustria, the Arnulfing Pippin faced the powerful Ebroin and the Merovingian king Theuderic III. Pippin had been defeated by Ebroin in 680, but he survived his rival, who was assassinated and whose murderers gained asylum at Pippin’s court. Ebroin’s successor made peace with Pippin but was deposed by his own son, Ghislemar. Both Ghislemar and his successor, Berchar, remained on bad terms with Pippin, and war once again broke out between the mayors of Austrasia and Neustria.

The war broke out as a result of the long-standing hostility between the Austrasian and Neustrian leaders and the civil strife in Neustria. Berchar had alienated many Neustrian nobles, who joined Pippin and invited him to become involved in the struggle in Neustria. According to one near-contemporary, pro-Carolingian account, Pippin asked his followers to join him in war against the Neustrians. Pippin sought war, according to this account, because Theuderic and Berchar rejected his appeals on behalf of the clergy, the Neustrian nobility asked for aid, and he desired to punish the proud king and his mayor. Pippin’s followers agreed to join in the war, and after marshalling his troops, Pippin moved along the Meuse River to meet his rival. Theuderic, learning of the advance of Pippin, levied his own troops, and he rejected, on Berchar’s advice, any offers of a peaceful settlement from Pippin. Having been rebuffed, Pippin prepared for battle and at dawn on the day of battle at Tertry quietly moved his troops across the river. Theuderic and Berchar, learning that Pippin’s camp was empty, moved in to plunder it and were ambushed by Pippin’s army. The king and his mayor fled while their troops were massacred. Berchar too was killed while wandering, and Pippin captured Theuderic, along with the royal treasury. The victor at Tertry, Pippin took control of the king and his wealth and united the three kingdoms of Austrasia, Burgundy, and Neustria under his authority. The Battle of Tertry was a significant victory for Pippin and his descendants, but it was only under his son, Charles Martel, and grandson, Pippin the Short, that power was consolidated in Carolingian hands.

Bibliography

Bachrach, Bernard S. Merovingian Military Organization, 481–751. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1972.

McKitterick, Rosamond. The Frankish Kingdoms under the Carolingians, 751–987. London: Longman, 1983.

Riché, Pierre. The Carolingians: A Family Who Forged Europe. Trans. Michael Idomir Allen. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1993.