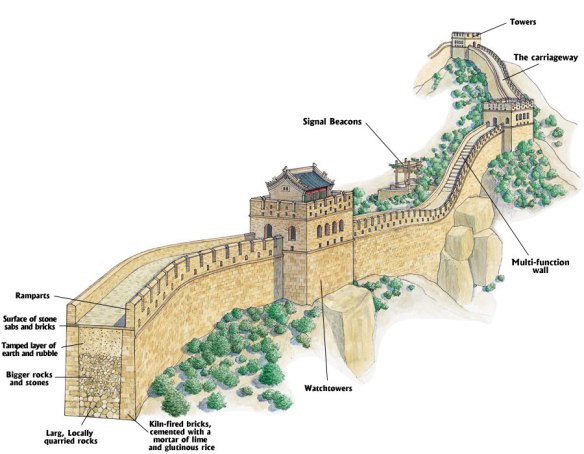

Construction of defensive walls began during the reign of China’s ‘‘First Emperor,’’ Qin Shi Huang, in 221 B.C.E. These connected sections of preexisting border fortifications of Qin’s defeated and annexed enemies, dating to the Warring States period, from which the Qin empire had emerged as victor. The building technique of this remarkable structure was the ancient method of stamped earth that employed masses of slave laborers as well as military conscripts. Some parts of the wall stood for nearly two millennia and were incorporated into the modern ‘‘Great Wall’’ built by the Ming dynasty following the humiliation of defeat and capture of the Zhengtong Emperor at Tumu (1449). After he regained the throne in 1457, the Ming court decided on a purely defensive strategy and began building 700 miles of new defensive walls starting in 1474, fortifying the northern frontier against Mongol raiders. The Ming system involved hundreds of watchtowers, signal-beacon platforms, and self-sufficient garrisons organized as military colonies. Infantry were positioned along the wall to give warning. But the main idea was for cavalry to move quickly to any point of alarm and stop raiders from breaking through. In that, the Ming strategy emulated Mongol practices from the Yuan dynasty. It was also reminiscent, though not influenced by, the Roman defensive system of ‘‘limes’’ which in Germania alone were 500 kilometers long.

The Great Wall was meant to reduce costs to the Ming of garrisoning a thousand-mile frontier by channeling raiders and invaders into known invasion routes to predetermined choke points protected by cavalry armies. This strategy was mostly ineffective. The Great Wall was simply outflanked in 1550 by Mongol raiders who rode around it to the northeast to descend on Beijing and pillage its suburbs (they could not take the city because they had no siege engines or artillery). The wall was also breached by collaboration with the Mongols of Ming frontier military colonies, which over time became increasingly ‘‘barbarian’’ through trade, marriage, and daily contact with the wilder peoples on the other side. Some Han garrisons lived in so much fear of the Mongols they were militarily useless; others lost touch with the distant court and hardly maintained military preparations at all. Finally, the Great Wall could always be breached by treachery or foolhardy invitation. Either or both occurred when a Ming general allowed the Manchus to enter China via the Shanhaiguan Pass to aid in the last Ming civil war in 1644, which brought the Ming dynasty to an end and put the Qing in power.

China never built a defensive wall along its Pacific sea frontier, as it felt no threat from that quarter. And yet, the main threat to its long-term stability and independence came across the Pacific in the form of European navies and marines. As with the 20th century Maginot Line in France, building the Great Wall in some ways signaled Ming defeatism rather than advertised Ming strength. The overall historical meaning of the Great Wall is ambiguous. To some, it signifies the worst features of China’s exploitative past; to others, it celebrates the longevity of China’s advanced, classical civilization.

Suggested Reading: Sechin Jagshid and V. J. Symons, Peace, War, and Trade Along the Great Wall (1989); Arthur Waldron, The Great Wall of China (1990).