The Qing had the largest army of any Chinese dynasty. It was so large they had to divide it into 8 huge banner armies.

Initially the banners were divided into ethnic lines, predominantly there were Manchu, Han Chinese, and Mongol banners. But shit got hairy when the Han armies returned home while Jurchen banners are out fighting, and Jurchen women began marrying returning Han men. Furthermore only the Chinese knew how to effectively use firearms while the Manchurians nor the Mongols don’t. So in the end each banner army ended up being multiethnic.

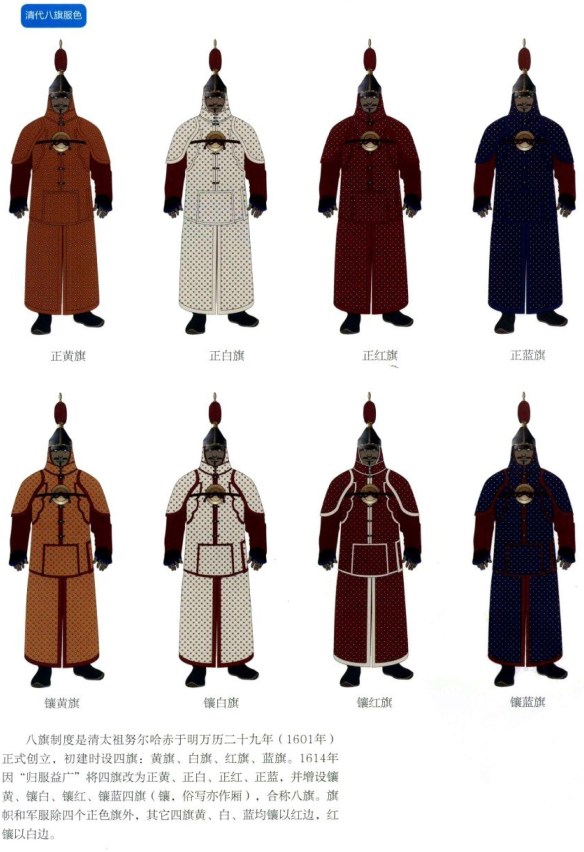

The main 8 banners armies were (from left to right, but jesus these are such obvious names).

-The Plain Yellow Banner Army

-The Plain White Banner Army

-The Plain Red Banner Army

-The Plain Blue Banner Army.

-The Bordered Yellow Banner Army

-The Bordered White Banner Army

-The Bordered Red Banner Army

-The Bordered Blue Banner Army.

There is also the Green Banner, but this is no army. This banner is assigned to any of the 8 banner armies who are spread out for garrison duty. Usuallym the practice is rotating the 8 banners into Green Banner roles.

The size of the armies in each of the banners were so large that there were essentially moving cities. Some soldiers live in banner armies their whole lives that their unit numbers become their family names (a Manchurian custom).

This organization is how the Qianlong Emperor managed to launch campaigns and invasions in almost every direction.

Along with shorter interregna and administrative integration, the third macro-historical parallel now requires more direct treatment is the long-term expansion of imperial territory. Admittedly, until the mid-1600s – in contrast to Southeast Asian states, Russia, and France – the territorial fortunes of successive China-centered empires showed no strong linear trend. That is to say, although imperial authority expanded in the southwest after 1253, losses elsewhere produced an oscillatory pattern from Han to Ming, with little, if any, net gain. The Qing, however, transformed the situation by joining agrarian China to steppe Inner Asia in a durable polity for the first time. This achievement thus corresponded to dramatic Russian conquests in Inner Asia (on which Qing success depended in part), as well as to extensive post-1650 acquisitions by Vietnam, Burma, and Siam and, less notably, Japan and France.

The Han empire at its height stretched from modern Gansu, the southern frontiers of Inner Mongolia, and central Korea in the north to Hainan island, northern Vietnam, Guangxi, and parts of Sichuan and Yunnan in the south. In order to combat the Xiongnu confederation of Inner Asian tribes, who in 166 b.c.e. had sent 140,000 horsemen to within 100 miles of the capital, the Han not only cultivated nomad allies, but outflanked the Xiongnu in the northeast, founding provinces in parts of modern Korea, and in the northwest, where a million colonists were sent to settle Gansu. What is more, to obtain horses and to secure anti- Xiongngu allies in the far west, Han forces established a protectorate that endured to the early first century c.e. in the southern part of modern Xinjiang.

This vast domain enjoyed only a modest organic unity. Large parallel river systems facilitate east–west communications, but much of West and South China is mountainous. Areas north and west of China proper are either completely unsuited or marginally suited for agriculture and thus incapable of supporting a Chinese-style social order. That the Han could hold together China proper, northern Korea, northern Vietnam, and areas in Xinjiang as long as it did speaks, we shall see, to cultural symbolism and administrative standardization as well as to early military prowess.

With the fragmentation that accompanied the collapse of the Later Han, non-Chinese tribal power flowed into North China, producing through the late 6th century a series of unstable Sino-foreign regimes and generating a political culture that embraced both the steppe frontier and much of North China, but that grew increasingly distinct from that of South China. It was, in fact, from the mixed blood Sino-foreign northwest military aristocracy that the founders of the Sui and Tang dynasties emerged to reassemble the basic Han ecumene. After wresting control of much of what is now Inner Mongolia from Turkic peoples, Tang forces recreated a short-lived protectorate in modern Xinjiang and reasserted control over northern Vietnam. But in Korea and Southwest China newly risen local states excluded the Tang from areas once dominated by the Han. Tang authority in Inner Asia was also unstable, with frequent challenges by early Turks and Tibetan-related groups.

In part because its ruling family was at least half Turkic and had access to both Inner Asian and Chinese traditions, the Tang was the last dynasty until the Mongol Yuan to control both South China and significant areas in Inner Asia. All along its northern frontier the Song faced foes it was unable to dislodge and to whom indeed it began to pay heavy tribute. In the northwest the Xi Xia state of the Tanguts, a semisedentary people related to the Tibetans, and in the northeast the Liao state of the Khitans, who were pastoral nomads, ruled mixed populations of Inner Asians and Chinese. The Liao state fell to Jurchen tribes from Manchuria, whose Jin Dynasty, as noted, expelled the Song from all of North China in 1127. In turn, the Mongols destroyed both the Jin and the Southern Song. While it is true that the Song held out against the Mongols longer than any other power – no mean feat, surely – their military power was never commensurate with their demographic and commercial superiority. Whether because of the chronic northern threat or internal weakness, the Song also were obliged to accept the independence of Vietnam and of the kingdom of Dali in Yunnan.

The last Chinese-led dynasty, the Ming, improved on Song performance insofar as the early Ming expelled the Mongols from China proper, pushed briefly into the steppe, and regained substantial territories formerly held by the Xi Xia and Liao polities. The Ming also took over southwest areas once controlled by Dali. Although it would later contract, Ming territory in 1470 was appreciably larger than Northern Song territory in 1102. But in truth neither of the last two Chinese-led dynasties, the Song or the Ming, could compete effectively with Inner Asian cavalry. This weakness became manifest not only in Song failures vis-`a-vis Xi Xia, Liao, and Jin and in Song extinction at the hands of the Mongols, but in the Ming’s increasingly defensive posture. After early victories against the Mongols, the Ming suffered humiliating reverses – in 1449 the emperor himself was captured on campaign in the steppe – after which Ming strategy stressed static defense. This was the true origin of the Great Wall. Internecine Mongol strife subsequently reduced dangers in the north, but that was replaced by an ultimately fatal Manchu threat in the northeast. Even the Ming’s improved territorial performance vis-`a-vis the Song reflected, in large part, the fact that the Mongols had temporarily obliterated other Inner Asian powers – Xi Xia and Jin – that could threaten China proper and, in order to outflank the Southern Song, had destroyed Dali. As John Dardess quipped, by eliminating non-Chinese regimes all along the frontier, the Mongols did China a favor that it had been unable to do for itself.

In other words, the major post-Han territorial extensions occurred not under Chinese, but Inner Asian-dominated regimes that, by wedding tribal military organization to Inner Asian and Chinese political traditions, softened the divide between frontier and sown. The Manchus continued these earlier patterns in two respects: First – like Tanguts, Khitans, Mongols, and Jurchens (from whom Manchus claimed descent) – Manchus were a non-Chinese conquest elite who emphasized clan-based politics, ethnic domination, polyglot administration, and the power of the military class. Second, almost four centuries after the Mongols tried to join all of China and vast stretches of Inner Asia in a single empire, the Qing resumed that project.