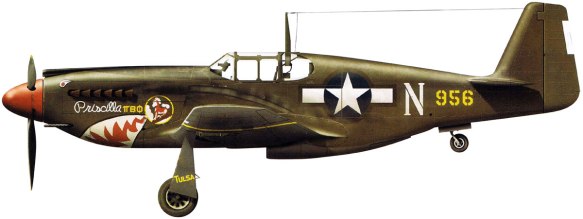

A-36 “Priscilla/Mavonne”, Unit: 526th FS, 86th FB, USAAF, Serial: N (956)

Pilot – Bert Benear. Mavonne – crew CO’s wife name, Priscilla – name of Benear colleague girl-friend.

Activated on 10 February 1942, as the 86th Fighter Group at Will Rogers Field, near Oklahoma City, Oklahoma with a cadre of five officers and 163 enlisted men. The unit made several moves before settling at Key Field in Meridian, Mississippi, where it began training on A-20 and DB-7 Havoc. In September 1942, the 86th was redesignated a dive-bomber unit and received A-24 Banshee, the Army Air Forces version of the US Navy’s highly successful SBD Dauntless, and A-31 Vengeance aircraft, transferring its A-20s and DB-7s to the 27th and 47th Light Bomber Groups.

The new aircraft did not improve the 86th’s combat capability. The Allies had found land-based dive bombers unsatisfactory for combat in Europe after the initial days of the war, so the A-24 and A-31 were as replaced as rapidly as possible. The transition began 20 Nov. 1942, with the arrival of the first A-36 Apache (also christened the Apache or Invader), one of the finest ground-attack aircraft in the world at the time and a version of the P-51A Mustang.

After completing training, in March 1943 the 86th and its three squadrons, the 309th, 310th, and 312th Bombardment Squadrons (Light) embarked from Staten Island 29 April and sailed to Algeria, arriving at Mers El Khebir, a former French naval base at Oran, in May. Flying operations began 15 May from Médiouna Airfield, near Casablanca, French Morocco. The 86th and its squadrons then began a series of moves around the theater which would eventually lead to Sicily, Italy; Corsica, France; and Germany.

In the North African Campaign, the 86th engaged primarily in close support of ground forces, beginning in early July against German positions in Tunisia. The 309th Squadron flew the group’s first combat mission on 2 July 1943 from Trafaroui Air Base, Algeria, and the group’s other squadrons began combat operations on 6 July with attacks against Cap Bon, Tunis.

On 14 July, initial elements of the 86th embarked for Comiso Airport, Sicily. The entire group settled into the airfield at Gela West, by 21 July. The following day the group flew its first mission from that base, supporting the 1st Division of II Army Corps. By the time the Germans withdrew from Sicily on 17 Aug., the group had flown 2,375 combat sorties in Sicily and along the southern coast of Italy.

The group was redesignated the 86th Fighter Bomber Group on 23 Aug. 1943, and its squadrons, the 309th, 310th, and 312th Bombardment Squadrons (Light) redesignated the 525th, 526th and 527th Fighter-Bomber Squadrons. On 27 Aug., the newly designated group moved to Barcelona Landing Ground, Sicily where the group provided air support for the first Allied landings on the European mainland at Salerno, Italy. On 10 Sept. 1943, three days after the invasion of Salerno, advance echelons of the 86th moved to Sele Airfield, near the beachhead. Enemy shelling of the beaches caused considerable difficulty during the move, and the group did not fly its first missions until 15 September.

After the fall of Naples, the group moved to Serretella Airfield, then on to Pomigliano d’Arco where it remained for some time. Throughout 1943–44, the 86th FBG supported Allied forces by attacking enemy lines of communication, troop concentrations and supply areas. Then, on 30 April 1944, the 86th moved to Marcianise Airfield to prepare for the spring offensive against the German Gustav Line. It also attacked rail and road targets and strafed German troop and supply columns during late spring, earning a Distinguished Unit Citation (DCU) for outstanding action against the enemy on 25 May when the group flew 12 armed reconnaissance and bombing missions and 86 sorties, destroyed 217 enemy vehicles and damaged 245, silenced several gun positions, and interdicted the highways into the towns of Frosinone, Cori, and Cescano. The group suffered heavy losses—two aircraft lost, six others heavily damaged, and one pilot killed.

The 86th was an active participant in Operation Strangle, the attempt to cut German supply lines prior to the Allied offensive aimed at rail and road networks, and attacking German troop and supply columns. While Strangle did not significantly cut into German supplies, it did disrupt enemy tactical mobility and was a major factor in the Allies’ eventual breakthrough. During this period the 86th received P-40 Warhawks to augment its aging A-36s, but the obsolescent P-40s were only a stopgap measure. On 30 May 1944, the 86th received its final wartime designation, the 86th Fighter Group, but more importantly the group welcomed its first P-47 Thunderbolts a few weeks later, on 23 June. The tough, modern P-47 was welcomed by the group’s pilots, as was their move to Orbetello Airfield, on the west coast of Italy, between 18 and 30 June.

In mid-July, the 86th continued its tour of the Italian coast by moving to Poretta Airfield, near Casamozza, on the island of Corsica. From Poretta, the fighter group flew bombing missions against coastal defenses in direct support of Operation Dragoon, the Allied invasion of southern France 15 Aug. 1944. Allied forces met little resistance as they moved inland twenty miles in the first twenty-four hours. Once the invasion was completed, the 86th moved back to Grosseto Airfield, Italy and continued its coastal basing by attacking enemy road and rail networks in northern Italy and, for the first time, flying regular escort missions with heavy bombers. The group also conducted armed reconnaissance against the enemy in the Po Valley region.

In October, 1944, the 86th was ordered to move to a new base in Pisa, Italy, but the weather turned bad, limiting the group’s combat flying and impeding its movement to Pisa. Finally, on 23 Oct., the first echelon moved to Pisa while the main body remained at Grosseto, but severe floods at both locations hampered the move. It was 6 Nov. before the 86th FG finally completed the move to Pisa.

The group continued combat in northern Italy until February 1945, when it left the Mediterranean Theater and moved to Tantonville Airfield (Y-1), France, in the Lorraine region, and operations shifted from targets in the Po Valley to those in southern Germany. The group’s first mission to Germany – a cause of some excitement – was on 25 Feb. 1945, and by March most missions were flown into Germany against rail lines, roads, supply dumps, enemy installations and airfields. The 86th FG transferred from Tantonville to Braunshardt Airfield (R-12), near Darmstadt, Germany, in April. A “maximum effort” on 20 April to stop all enemy transportation in southern Germany earned the group its second Distinguished Unit Citation. The 86th Fighter Group flew its final combat mission on 8 May 1945. By the end of that war, the group had flown a total of 28,662 combat sorties and claimed the destruction of 9,960 vehicles, 10,420 rail cars, 1,114 locomotives and 515 enemy aircraft.

Just after the war, the group performed occupation duty at Braunschardt (Now designated AAF Station Braunschardt) which became a replacement depot to process troops returning to French staging areas for shipment home. Flying personnel performed routine training to maintain their proficiency. On 25–26 Sept. 1945, the group moved to AAF Station Schweinfurt, Germany to begin operations as a unit of the occupation force. The group’s squadrons lost their personnel without replacement in October – November, and the group headquarters began absorbing all squadron personnel in October, completing the shift on 24 Nov. 1945

At midnight on 14 Feb. 1946, group headquarters personnel were assigned to Detachment A, 64th Fighter Wing. The designation of the group and squadrons moved, without personnel or equipment, to Bolling Field, Washington, DC, to join Continental Air Forces (later, Strategic Air Command). However, Continental Air Forces had a surplus of units and on 31 March 1946, the 86th and its units were deactivated and its aircraft being sent to the new “Schweinfurt Air Depot” operated by Air Technical Service Command for deposition.