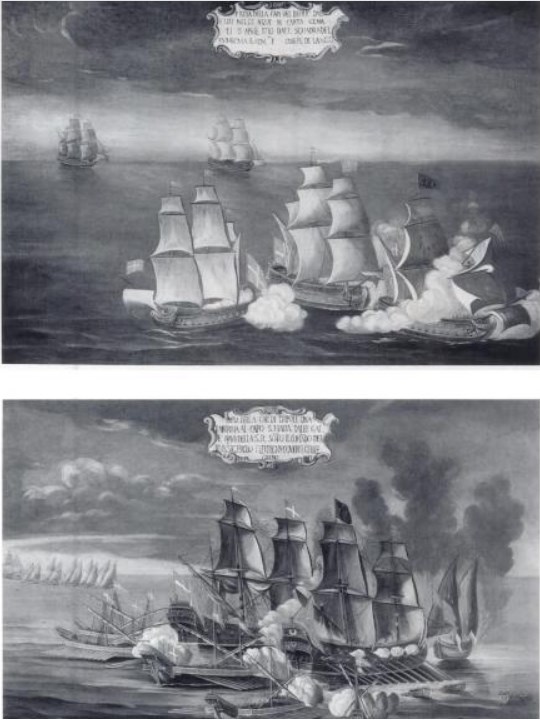

Views of two actions of the navy of the Order, early eighteenth century.

The period following 1723 has been described by historians of the Order of St John as one of naval decline. For all its prevalence, that view is founded on a primal ignorance of the area most relevant to the question: the development of the North-African states, of which a brief outline is necessary. All three of the Regencies succeeded in increasing their independence from Turkey at the beginning of the eighteenth century, and two of them accompanied this with an expansion of their real power. Algiers conquered Oran and Mazalquivir from Spain in 1708; Tunis remained weak and subject to Algerian intervention. Tripoli is the case most pertinent to our subject: the corsairs, driven from the other Regencies, had taken refuge here, and Tripoli re-emerged as a strong corsair centre in the second half of the seventeenth century. The position of the Regency was further strengthened by the accession of the Caramanli dynasty in 1711; its founder, Ahmed Bey, extended his rule to Cyrenaica, exacted tribute from the Fezzan, and sought to build up his naval power.

Parallel to these developments came the breakup of Spain’s Italian dominion as a consequence of the War of Succession. Sardinia was granted to the Dukes of Savoy in 1720; Naples was weakly held by Austria from 1707 and became independent under Bourbon rule in 1734. As a result, instead of a single empire defended by the Spanish navy (and here, for naval purposes, we should include the Papal States), there were left three minor powers, each with an insignificant fleet and each pursuing its independent defence. These were conditions which the Barbary states could have exploited to achieve local dominance in the central Mediterranean; that they did not do so is due essentially to the Order of St John.

The first signs of the reponse to the new threat appear at the beginning of the eighteenth century. In its alliance with the Venetians, the Order had found it most efficient to specialise in galley warfare; now, however, it was faced with a serious naval rival nearer home, against whom it had to fight alone. The decision was therefore taken to diversify the fleet, to reduce the number of galleys to five (later four) and to build four ships of the line, of between fifty and sixty guns, to which a fifth captured one was quickly added. This mixed fleet first put to sea in 1705 under Castel de Saint-Pierre, who had a grand design to sweep the Barbary corsairs from the Mediterranean with the support of the European powers. As the latter were busy fighting each other, his plan had little chance of being realised, but for the next half-century the Knights of Malta struck a series of formidable blows at the Tripolitanian navy, preventing the Bey from matching his power on land with corresponding power at sea.

An early success was the capture of the Soleil d’Or in 1710 by Joseph de Langon, who was killed in the action. The figure most closely associated with the feats of the sailing squadron was the ferocious Jacques de Chambray, a strong advocate of the superiority of the ships of the line, who in 1723 received the command of the Saint-Vincent, of 52 guns, with a crew of 300. In his first cruise, sailing off Pantelleria, he came upon the Vice-Admiral of Tripoli with an armament of 56 guns and a crew of 400, and captured the ship after a fierce fight, winning the most important victory for the Order since 1700. Chambray’s exploits continued for another twenty-six years, until he retired in 1749 with a string of victories behind him. Under his command, the mixed fleet of the Order attained, in the 1740s, the peak of its strength, with six sailing ships (three of them of 60 guns) and four galleys. As a consequence, Tripoli was obliged to recognise defeat, and under Ali Caramanli (1754-93) a semblance of friendly relations was maintained with Malta, peaceful trade being developed between the two countries.

An achievement of less immediacy, but striking in the longer historical view, was the blocking of the recovery of Tunis. That city had traditionally enjoyed one of the most favoured positions on the North-African coast, as was shown by its own greatness in the Middle Ages and that of Carthage in antiquity. Yet from the time of the knights’ arrival in Malta the days of Tunis as a nodal point in the Mediterranean were numbered. Competing with it for mastery over the Straits of Sicily, the Knights of St John ensured that Tunis remained the weakest of the Barbary Regencies, transferring to their own island the centrality that had belonged to its African neighbour.

The myth of naval decadence therefore needs to be replaced with a different analysis: until 1722 the Knights of Malta had fought Turkey in alliance with the other Christian powers, and their role in that conflict had necessarily been that of auxiliaries, however brilliant. After the truce of 1723 the stage was narrowed, but the knights’ role became a central one, and we find them operating in the middle years of the eighteenth century with a greater degree of independent effectiveness than at any time since the Rhodian period. Their influence can be illustrated by drawing a circular map of a thousand miles’ diameter centred on Malta; this area was occupied by two Moslem and three Christian states whose naval weakness was on the one side enforced, on the other protected, by the navy of Malta. Only on the north-eastern fringe of the circle does Maltese sea-power give way to Venetian. The Order exercised this role not only directly but through its function as a naval academy for the European fleets. The Papal States, Naples and Sardinia (none of which had a navy equal in strength to Malta’s) would have had no officer corps worth looking at without the Knights of St John. Thus the local balance of naval power in this vast area revolved round Malta and its few hundred knights, who succeeded in crippling the maritime development of North Africa. That this achievement appears a small one – that we take the weakness of the African states for granted – is itself a measure of its success: in the early seventeenth century the Barbary Regencies had been naval powers on a level with England and France; in the eighteenth, if the Order of Malta had not stood in their way, conditions were ripe for them to recover a portion of their dominance at the expense of the Italian states.

By the last third of the century the knights’ success was so complete that they seemed to have left themselves nothing further to do. The Regencies had stopped building anything but xebecs and similar small craft, because any larger ship was immediately captured or destroyed by the Knights of Malta. As a consequence we find a gradual reduction in the strength of the Maltese navy and a shift to bombarding operations (such as the support for the French attack on Tunis in 1770) and in particular to action against Algiers, which remained the only significant corsair base. The Algerians were attacked in 1772, 1775, 1783 and 1784 in collaboration with Spain, which was making an effort at this time to dispose finally of its ancestral enemy. In 1784 a ship of the line and three galleys supported the Spanish attack on Algiers, after which the Maltese squadron remained cruising in Algerian waters, at Spain’s request, maintaining pressure on Algiers in preparation for a further campaign the following year. Unfortunately Spanish resolution petered out into an unsatisfactory peace treaty; the opportunity of a decisive victory was lost, and Algiers lived to plague Christian shipping for a further forty-five years.

The appearance that the corsair threat had become negligible was nevertheless delusive. Such activity had always shown a resurgence in a period of general war, especially one in which both Spain and France were involved (for example in the 1740s and early 1760s); and the Mediterranean was about to witness one of the longest such periods in its history. The years 1793 to 1814 permitted the Barbary corso to recover a vigour it had not known for a long lifetime. Algiers increased its corsair strength from ten small vessels and 800 Christian captives in 1788 to thirty ships and 1,642 captives in 1816. Tunis and Tripoli enjoyed a similar revival. At first this trend was contained by corresponding activity in Malta: not only did the corso revive (nine privateers were licensed in 1797 alone) but the navy redoubled its efforts and in the five years 1793-98 it captured eight prizes, almost as many as in the whole of the previous thirty years. The last of these was taken only a few days before the French attack on Malta.

Despite its greater strength, the British navy based in Malta after 1800 did little to continue the work of the Order of St John except in the interests of its own trade. Algiers remained a corsair centre until its conquest by the French in 1830. Tripoli, under Yusuf Caramanli (1795- 1832), became a serious nuisance to many countries, as was demonstrated by the repeated expeditions against him: by the United States in 1803-5, by Britain in 1816, by Sardinia in 1825, by Naples in 1828 (a disaster for the Neapolitan navy), and by France in 1830. The expulsion of the knights from Malta thus underlined the impartial policing work they had performed for the benefit of all nations and the remarkable naval effectiveness they had maintained in the central Mediterranean.