Battle of the Basque Roads

The flamboyant, Captain Lord Cochrane, had rockets sent out onboard the transport Cleveland, to Basque Roads the same year, for his attempt on the French fleet anchored there. These rockets were fired from the rigging of the fire ships when sent in to attack the French fleet; however they endangered the British boats as much as the French fleet and did little damage. William Congreve was the eldest son of an official at the Royal laboratory at Woolwich. Congreve had served in the Royal Artillery briefly in 1791 before being attached to the laboratory staff himself. Congreve worked on improving the propellants and inventing warheads for the rocket. Congreve’s own story of his work on rockets begins.

‘ In 1804, it first occurred to me that….the projectile force of the rocket…….might be successfully employed, both afloat and ashore, as a military engine, in many cases where the recoil of exploding gunpowder’ made the use of artillery impossible. Congreve bought the best rockets on the London market but found they had a greatest range of only 600 yards. He knew that the Indian princes had possessed rockets that would travel much further than this. After spending ‘several hundred pounds’ of his own money on experiments he was able to make a rocket that would travel 1500 yards. He applied to Lord Chatham to have a number of large rockets constructed at Woolwich Arsenal, these achieved ranges of up to 2000 yards. By 1806 he was producing 32pdr rockets, which flew 3000 yards. The great advantage of Congreve’s invention was that it possessed many of the qualities of artillery but was free from the encumbrance of guns; wherever a packhorse or an infantryman could go, the rocket could go and be used to provide artillery support.

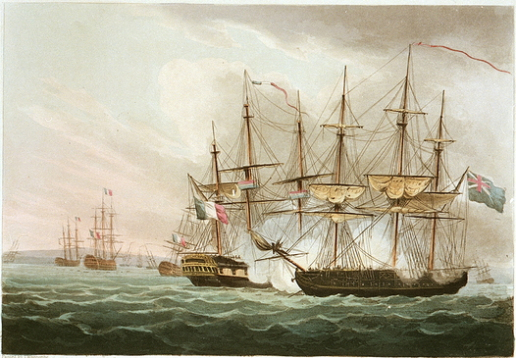

The attack by the Royal Navy on vessels at Basque Roads on the west coast of France in 1809 was a successful attempt to counter French moves against British interests in the West Indies and to prevent the French from reinforcing their colony of Martinique.

In 1808 the French learned of an intended British expedition to the West Indies. To oppose this, Rear Admiral Jean-Baptiste Willaumez was ordered to sail from Brest at the first sign that the British blockade had been relaxed. He was to relieve the blockade at Lorient, release the fleet of eight ships under Commodore Aimable Gilles Troudes, and sail to Basque Roads, where he was to combine his forces with a further three ships of the line, several frigates, and the troopship Calcutta. The fleet was to sail to the West Indies with the purpose of disrupting British trade and supporting the garrison of Martinique.

On 21 February 1809 the blockading ships of Admiral James Gambier were forced by storms to withdraw from their position off Ushant. This gave Willaumez the opportunity to slip out of port and sail south. The maneuver was observed by the Revenge, which followed the French south toward Lorient, where Commodore Sir John Beresford lay off the port with three ships. On 23 February, Beresford pursued the French, who discovered they were being driven toward another British force under Rear Admiral Sir Robert Stopford. Faced with this superior force, Willaumez took his fleet into Basque Roads.

Meanwhile, three French 40-gun frigates had left Lorient under Commodore Pierre Roch Jurien and sailed to join Willaumez, anchoring under the shore batteries. Stopford’s four ships of the line engaged the enemy frigates and shore batteries, setting two frigates on fire and driving the other aground. All three French ships were wrecked. Meanwhile, Willaumez’s force had lost one ship, driven onto a shoal in Basque Roads, but had joined the squadron there of three 74-gun ships of the line and two 40-gun frigates. A heavy boom was placed across the passage into the anchorage. Willaumez was bottled up, but the Admiralty was concerned that the French might yet slip out and reach the West Indies, and so the decision was made to destroy the enemy fleet.

On 19 March, Gambier was told that twelve transports and five bomb vessels (special ships carrying mortars for shore bombardment) were being prepared for what was to be an extremely hazardous operation. Captain Lord Cochrane of the Impérieuse was appointed to lead the attack. He had the reputation of being a daring and energetic officer and could conveniently be blamed if the attack proved a disaster. On the French side, however, Willaumez had been removed from command for failing to do battle with Beresford’s inferior force off Lorient.

Under Cochrane’s supervision, eight of the British transports plus the old frigate Mediator were being fitted out as fire ships, with barrels of tar and other combustible materials arranged on their decks, while two further transports and a captured French coaster were converted into explosion vessels, being packed with gunpowder, shells, and grenades. Meanwhile, twelve further fire ships had arrived on 10 April together with the bomb vessel Aetna. A number of smaller craft were also fitted out to fire Congreve rockets.

The British force, under Gambier, consisted of the 120-gun Caledonia, two 80-gun ships, eight 74-gun ships, one 44-gun heavy frigate, four other frigates, three sloops, seven gun brigs, three smaller craft, twelve fire ships, and the bomb vessel Aetna. The French force, under Rear Admiral Zacharie Jacques Allemand, was composed of an inner line made up of the ships Elbe (40 guns), Tourville (74), Aquilon (74), Jemmappes (74), Patriote (74), and Tonnère (74); a center line, of the ships Calcutta (troopship), Cassard (74), Regulus (74), Océan (120), Ville de Varsovie (80), and Foudroyant (80); and an outer line, of the ships Pallas (40), Hortense (40), and Indienne (40). He also had the support of shore batteries manned by 2,000 troops. Allemand anchored his ships in three lines north to south with a 2-mile boom of anchor cables protecting the approach to Basque Roads.

At 8:30 P.M. on the night of 11 April, some British fire ships sailed for the enemy. At 9:30 P.M., Cochrane ordered the fuses lit, and these ships exploded, destroying the boom. Other fire ships were now able to sail through the debris, but now the plan began to go wrong. Several of the fire ships were ignited too soon, many either running aground before reaching the anchorage or sailing harmlessly up the center of the channel. However, the few such ships that reached the French caused much confusion, combined with shells from the Aetna, the Congreve rockets, and broadsides from other British vessels. Some of the French ships broke free of the line to escape the fire ships. The Regulus got clear of one, only to collide with the Tourville. Hortense escaped one fire ship and fired upon another, only to hit other French warships. Océan ran aground and was then hit by a fire ship that her crew, however, managed to fend off, but she was then rammed by the Tonnere and the Patriote.

Dawn revealed a scene of devastation within the French fleet. Cochrane asked Gambier for reinforcements to complete the destruction of the enemy, but the latter only ordered the bomb vessels to shell the French, much to Cochrane’s frustration. Only the Foudroyant and Cassard were still afloat—the other vessels were all aground—but even these two ships eventually ran aground. Four of the French ships were eventually refloated, only to run aground again at the entrance to the anchorage. Cochrane took the Impérieuse inshore and by 2:00 P.M. on 12 April was engaged with the Calcutta, the Aquilon, and the Ville de Varsovie. This prompted Gambier to send support, forcing the three French vessels to strike. Two other ships, the Tonnère and the Calcutta, both caught fire and exploded. Cochrane moved closer with the gun brigs, despite repeated orders from Gambier to retire. On 14 April, after a final attack by the Aetna and gun brigs, four of the French ships managed to escape upriver, while two others grounded attempting the same maneuver.

The French government treated this disaster harshly. The French commanders were tried by court-martial; two were imprisoned, and Captain Jean Baptiste Lafon of the Calcutta was condemned and shot. On the British side, there was much criticism of Gambier for not having supported Cochrane more vigorously. However, the French plan to attack the West Indies had been thwarted.

Order of battle

British

Caledonia (120)

Caesar (80)

Gibraltar (80)

Donegal (74)

Bellona (74)

Hero (74)

Illustrious (74)

Resolution (74)

Revenge (74)

Theseus (74)

Valiant (74)

Imperieuse (38)

Aigle (36)

Unicorn (32)

Pallas (32)

Indefatigable (44)

Emerald (36)

Mediator (32)

Beagle (18)

Doterel (18)

Foxhound (18)

Insolent (14)

Encounter (12)

Conflict (12)

Contest (12)

Fervent (12)

Growler (12)

Lyra (10)

Redpole (10)

Whiting (4 – fitted as rocket ship)

Nimrod (10 – fitted as rocket ship)

King George (10 – fitted as rocket ship)

Thunder (8) (bomb)

Ætna (8) (bomb)

40 transports or fireships

3 Congreve rocket barges

French

Océan (118) (flagship)

Ville de Varsovie (80) (burnt)

Foudroyant (80)

Jemmapes (80)

Cassard (74)

Régulus (74)

Tourville (74)

Aquilon (74) (burnt)

Patriote (74)

Tonnerre (74) (scuttled)

Calcutta (54) (scuttled)

Pallas (46)

Hortense (46)

Indienne (46) (scuttled)

Elbe (46)

Other smaller ships

References and further reading Clowes, William Laird. 1996. The Royal Navy: A History from the Earliest Times to 1900. Vol. 5. London: Chatham. (Orig. pub. 1898.) Cochrane, Admiral Lord. 2000. The Autobiography of a Seaman. London: Chatham. Grimble, Ian. 2001. The Sea Wolf: The Life of Admiral Thomas Cochrane. Edinburgh: Birlinn. Harvey, Robert. 2002. Cochrane: The Life and Exploits of a Fighting Captain. London: Constable and Robinson. Woodman, Richard. 1998. The Victory of Seapower: Winning the Napoleonic War, 1806–1814. London: Chatham.