“The Falls” choke point on the Ho Chi Minh Trail in southern Laos. This photo was taken by a forward air controller (FAC) named Jim Roper.

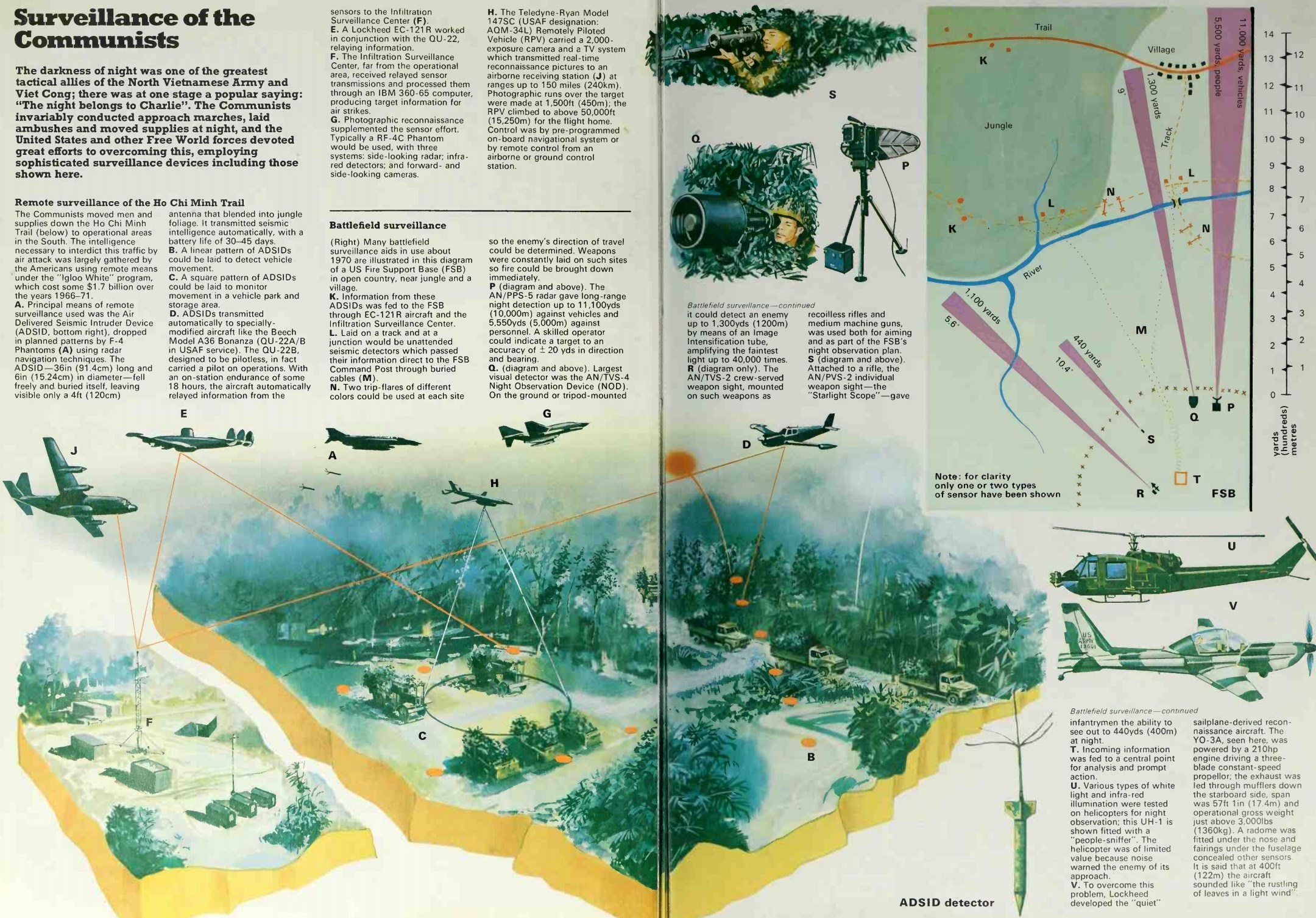

The most stunning failure was in the US bombing campaigns over the Ho Chi Minh Trail. They had little or no success in cutting off the Vietcong and North Vietnamese troops from their supply bases above the seventeenth parallel. In 1963 the Trail had been primitive, requiring a physically demanding, month-long march of eighteen-hour days to reach the south. But by the spring of 1964, the North Vietnamese put nearly 500,000 peasants to work full and part time and in one year built hundreds of miles of all-weather roads complete with underground fuel storage tanks, hospitals, and supply warehouses. They built ten separate roads for every main transportation route. By the time the war ended, the Ho Chi Minh Trail had 12,500 miles of excellent roads, complete with pontoon bridges that could be removed by day and reinstalled at night and miles of bamboo trellises covering the roads and hiding the trucks. As early as mid-1965 the North Vietnamese could move 5,000 men and 400 tons of supplies into South Vietnam every month. By mid-1967 more than 12,000 trucks were winding their way up and down the trail. By 1974 the North Vietnamese would even manage to build 3,125 miles of fuel pipelines down the trail to keep their army functioning in South Vietnam. Three of the pipelines came all the way out of Laos and deep into South Vietnam without being detected.

The Ho Chi Minh Trail had become a work of art maintained by 100,000 Vietnamese and Laotian workers. It included 12,000 miles of well-maintained trails, paved two-lane roads stretching from North Vietnam to Tchepone, just across the South Vietnamese border in Laos, and a four-inch fuel pipeline that reached all the way into the A Shau Valley. The CIA estimated that between 1966 and 1971 North Vietnam had shipped 630,000 soldiers, 100,000 tons of food, 400,000 weapons, and 50,000 tons of ammunition into South Vietnam along the Ho Chi Minh Trail. Abrams wanted to invade Laos, cut the Ho Chi Minh Trail, and starve the North Vietnamese troops waiting in South Vietnam. But because the Cooper-Church Amendment prohibited the use of American troops outside South Vietnam, Abrams would have to rely on ARVN soldiers. During Nixon’s first two years in office, nearly 15,000 American troops were killed in action.

The Nixon administration debated an invasion of Cambodia or North Vietnam, but Abrams argued forcefully for severing the enemy supply lines in Laos. Nixon, Kissinger, and Westmoreland ultimately agreed with him. While the Winter Soldier Investigation was going on in Detroit, planning for the invasion of Laos was under way. Late in 1970 the United States 101st Airborne Division and the 1st Brigade of the 5th Infantry Division reoccupied the former marine base at Khe Sanh as a staging area for the campaign. To divert enemy attention, a navy task force with the 31st Marine Amphibious Unit aboard hovered off the North Vietnamese city of Vinh, threatening an invasion. The ARVN objective was to drive west from Khe Sanh up Route 9 to Tchepone, about twenty-five miles away, cutting across the Ho Chi Minh Trail.

South Vietnam committed 21,000 troops to the effort. Supported by B-52s and fighter-bombers from the American air force and navy, they invaded Laos on February 8, 1971. The attack was code-named Lam Son 719 after a small village in Thanh Hoa Province, the birthplace of Le Loi, the Vietnamese hero who had defeated an invading Chinese army in 1428. But Laos was not Cambodia. North Vietnam was protecting its lifeline there, not isolated sanctuaries. The region surrounding Tchepone contained 36,000 NVA troops-nineteen antiaircraft battalions, twelve infantry regiments, one tank regiment, one artillery regiment, and elements of the NVA 2nd, 304th, 308th, 320th, and 324th Divisions.

For the first twelve miles, the ARVN encountered only token resistance. But as heavy rains turned Route 9 to mud, the offensive fell short. The South Vietnamese troops fought well, but they were in an impossible position. ARVN air cavalry troops took Tchepone on March 6, but three days later Nguyen Van Thieu ordered a general withdrawal. It took two weeks of bitter fighting along Route 9 for the South Vietnamese to get back out of Laos, and without American air power they would not have made it at all. By the time they reached Khe Sanh, the South Vietnamese admitted to 1,200 men dead and 4,200 wounded, while MACV estimated the dead and wounded together at 9,000.

Abrams claimed publicly that Lam Son 719 had inflicted 14,000 casualties on the North Vietnamese. Back in Washington, President Nixon was even more effulgent, telling the White House press corps that “18 of 22 battalions conducted themselves with high morale, with greater confidence, and they are able to defend themselves man for man against the North Vietnamese.” In a televised speech on April 7, the president proclaimed, “Tonight I can report that Vietnamization has succeeded.” At the Pentagon, however, the private assessments were grim. Most of the ARVN troops had proven themselves, but in fact they suffered a major military defeat, besides having no success in severing the Ho Chi Minh Trail. The attack, as well as Vietnamization, was a failure.

The bombing was, to be sure, devastating. During the war the United States dropped one million tons of explosives on North Vietnam and 1.5 million tons on the Ho Chi Minh Trail. In 1967 the bombing raids killed or wounded 2,800 people in North Vietnam each month. The bombers destroyed every industrial, transportation, and communications facility built in North Vietnam since 1954, badly damaged three major cities and twelve provincial capitals, reduced agricultural output, and set the economy back a decade. Malnutrition was widespread in North Vietnam in 1967. But because North Vietnam was overwhelmingly agricultural-and subsistence agriculture at that-the bombing did not have the crushing economic effects it would have had on a centralized, industrial economy. The Soviet Union and China, moreover, gave North Vietnam a blank check, willingly replacing whatever the United States bombers had destroyed.

Weather and problems of distance also limited the air war. In 1967 the United States could keep about 300 aircraft over North Vietnam or Laos for thirty minutes or so each day. But torrential rains, thick cloud cover, and heavy fogs hampered the bombing. Trucks from North Vietnam could move when the aircraft from the carriers in the South China Sea could not.

Throughout the war North Vietnam, assisted by tens of thousands of Chinese troops from the People’s Liberation Army, gradually erected the most elaborate air defense system in the history of the world. They built 200 Soviet SA-2 surface-to-air missile sites, trained pilots to fly MiG-17s and MiG-21s, deployed 7,000 antiaircraft batteries, and distributed automatic and semiautomatic weapons to millions of people with instructions to shoot at American aircraft. The North Vietnamese air defense system hampered the air war in three ways. American pilots had to fly at higher altitudes, and that reduced their accuracy. They were busy dodging missiles, which consumed the moment they had to spend over their target and reduced the effectiveness of each sortie. And they had to spend much of their time firing at missile installations and antiaircraft guns instead of supply lines.