Black Conquistador: The Narvaez Expedition in Florida

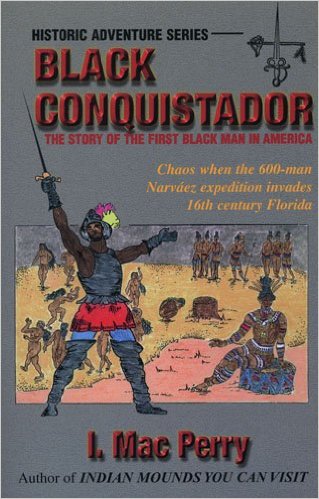

Don Francisco de Arove, age fifty-six, with his two sons, don Pedro, age twenty-two, and don Domingo, eighteen years old, painted and signed by a Quito artist, Andrés Sánchez Gallque, in 1599 for Philip III, identified as “King of Spain and the Indies.” The three maroon leaders are holding iron-tipped palm-wood lances, adorned with gold jewelry, wearing doublets, ponchos, silk capes, and white ruffs—all a combination of cloth and cut from China, Europe, and the Andes.

In 1553, a group of several dozen black slaves was shipwrecked off the coast of what is now Ecuador. They washed ashore, bereft, bedraggled, and with little or nothing in the way of weapons or supplies. Alonso de Illescas rapidly assumed the leadership of the castaways. He had been a slave in Seville, where he acquired Christianity and the rudiments, at least, of Spanish culture. Within a matter of months, he established a privileged relationship with the local native chief, whose daughter he married and whose heir he became. Before he succeeded to the chieftaincy, he and his companions helped the locals in their wars against neighboring tribes and acted in effect as the chief´s bodyguards.

The Spanish colonists in Quito—the nearest Spanish American city—strove for an understanding with “the black king of the Indians,” as they called him. At times they sent diplomatic missions to try to get his assent for a road from Quito to the port he controlled, and at others they sent armies in unsuccessful attempts to enforce compliance. Illescas obtained the title of governor for the king of Spain, and ostentatiously flourished the dignity, without sacrificing any of his independence.

The little state he created broke up after his death into a number of petty “kingdoms” ruled by descendants of his black lieutenants. In 1599, in Quito, the painter Andrés Sánchez Gallque portrayed one of them, don Francisco de Arove, with his sons, on the occasion of his visit to be invested with the rank of royal governor. The three black officials are sumptuously attired, in the height of aristocratic fashion, with ruffs so luxurious that in Spain the strict sumptuary laws would have forbidden them. In their ears and noses they wear golden ornaments of the kind that local natives reserved for the adornment of their rulers and the depiction of their gods. Within a few years, officials in Quito were complaining that the black officials remained as intractable and recalcitrant as ever. Their little kingdoms survived, effectively independent, for many generations.

The story resembles, in miniature, those of other—better known, Spanish, even famous—conquistadors. Strangers arrive, with no obvious advantages that might seem to destine them for power. They make themselves useful by virtue of the stranger-effect: their independence from traditional native factionalism makes them ideal in the roles of chiefly bodyguards and elite marriage partners. Their prowess in battle makes them enviable as allies. They exercise the influence of valued arbitrators. Indigenous society welcomes them with hospitality and rewards them with tribute, with services, and ultimately with power. They supply an additional level of leadership, supplementing or substituting or superimposed on traditional elites, rather than entirely displacing existing structures. Their success does not flow from superior weaponry, or horses, or any identifiable intellectual or moral advantage, or from the delusions of natives who mistook them for gods. On the contrary, it springs from well-disposed elements in native culture.

The trajectory to power of don Francisco de Arove and his colleagues was that of many or most of the Spanish conquistadors whose careers they seem to ape or mock. They, too, are conquistadors, and, perhaps, are as representative in their way as any of those whom the historical record has privileged—from the obvious Spaniards, such as Cortés and Pizarro, to the less obvious ones, such as Ursúa and Vargas Machuca. The category of conquistador is larger still, including such unconventional protagonists as Catalina de Erauso and don Francisco de Montejo Pech. Only by viewing the category as inclusive, and by appreciating the expansive nature of conquistador culture in the Americas, can we fully understand the conquistador phenomenon, the Spanish Conquest, and Latin American civilization.