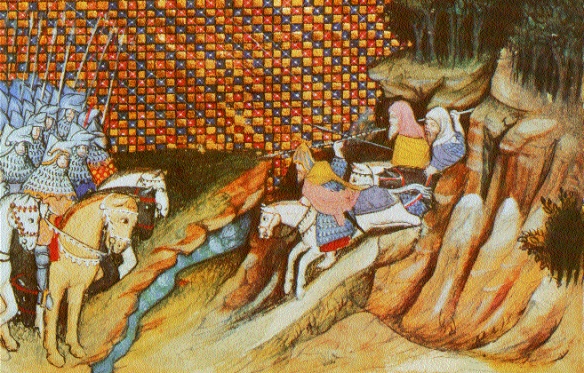

King of Leinster, Art Macmurrough (right), sallies forth to parley with Thomas, earl of Gloucester (left), Richard II’s envoy on his second (1399) Irish campaign. From the illustrated eye witness account of the campaign by Jean Creton. (British Library)

By late-June the king had spent roughly four weeks traversing Leinster and the up-lands of Wicklow seeking his enemies before moving on to Dublin. Modern historians generally agree that these weeks represent a failure for the king and his policies. They argue that by the time Richard arrived in Dublin he was no closer to restoring the “wild Irish” to royal authority than he had been at his landing at Waterford on 1 June. But the interpretation of these six weeks that Richard II spent in Ireland before news of Henry’s return reached him requires some revision. The fact that Richard had worked throughout the preceding eighteen months to build a large military force in Ireland, combined with his decision to stay in Ireland for one full year and the fact that he brought so much of his court with him strongly suggests that the king did not anticipate a quick solution to his Irish problems. It also seems that Richard did not expect to bring the Gaelic Irish to heel in a mere 30-day lightening campaign.

Nevertheless, the king had achieved some of his goals. He put a large and impressive English and Anglo-Irish army in the field, and he had moved through the country of Leinster to Dublin with ease. Although the Irish chieftains had, not surprisingly, avoided open battle with the superior English army, the king and his men had killed some Irishmen and kerns and captured others. More significantly, some Irish chiefs including MacMurrogh’s uncle had returned to his suzerainty. Even though Art MacMurrogh, the principal rebel, remained unbowed and at large, Richard had opened communications with him in the hope that, as it had in 1394/95, more could be achieved by diplomacy than by fire and sword. Establishing his court at Dublin complete with minstrels, ladies, and a portion of his Chancery demonstrates that the king was creating for himself, as he had in 1394/95, the position of ultimate adjudicator for all Irish disputes. Time, it seemed in early July, was on King Richard’s side.

Unfortunately for the king, his political and military situation in the emerald isle changed markedly for the worse in the second week of July when Richard first heard rumors and then confirmation that Henry of Lancaster had invaded England, apparently to reclaim his inheritance. Jean Creton claimed to have witnessed the king’s reaction to the news and said that he “turned pale with anger.” Although we have one eye-witness perspective of how the king received the news of Henry’s presence in England, exactly when and where Richard received that news is uncertain.

It is probable that the king heard rumor of Henry’s impending invasion as early as the first week of July. Propaganda and rumor of Henry’s advent appear to have been abroad in the land for some time, and several chroniclers confirm this. As we have seen, Duke Edmund had sent letters to the shires to raise troops as early as 28 June, and these letters were the source of Chester castle being put into a state of defense when they reached the sheriff there on 3 July. The sheriff of Chester then dutifully sent letters to Richard in Dublin, so even as early as 5 or 6 July, rumor of Henry of Lancaster’s return to England could have reached the king in Ireland.

How far and wide the news of Henry’s return spread to Irish and Anglo-Irish subjects is also difficult to gage. Dorothy Johnson suggests the king and his advisers were understandably reticent to make the contents of York’s letters public for fear that news of Henry’s arrival in England would cause desertion, but on the other hand news of this magnitude could not be kept quiet for long. Even if deserters would have fled Richard’s army they would have found themselves as Englishmen in a foreign country seeking aid from the very Irish they had just been trying to kill only days and weeks before. If fleeing into the Irish hinterland was a poor option, flight by sea was little better. The king had commandeered all available vessels for the return journey of his army and he held a number of vessels fitted out for war to hunt down any ships. Thus, there was nowhere for potential deserters to flee. In any event, the army that Richard led to Ireland was composed of a large number of his most loyal followers and, therefore, mass desertions seem highly unlikely. In fact, troops loyal to Richard’s cause were still under arms in Dublin as late as the end of September 1399 and only began to disperse themselves for want of pay and after learning of the king’s capture and deposition.

Edward of York most likely looked to his own ambitions in the summer of 1399, the most likely explanation for the delay in the king’s departure from Dublin is simple military logistics: the delay resulted from the king’s need to collect his forces before he could move south towards Waterford. Military necessity had forced Richard to spread his troops over the countryside in the opening weeks of his campaign because of the interspersed nature of lands held by English lords and Irish chieftains. This meant that it would take at least several days to gather an army of sufficient size at Dublin before setting out for Waterford. Further complicating the speed of a return journey was the problem of transport. As we have seen, as Richard had done in 1394/95, he had retained a number of vessels for service throughout the summer. No doubt, some of these ships were engaged in transporting supplies and reinforcements coming out of the principality of Chester, while others were blocking the western coast of Ireland and engaging in economic warfare against Gaelic Irish merchantmen.

Quite probably on 11 or 12 July, the king and his advisers had no good idea of where all the ships they had retained for the summer were, and it would have taken time to bring sufficient numbers of them together to transport the army. The order from the king to gather these vessels engaged in the interdiction of the Irish coast at Waterford rather than further north up the coast at Dublin also turned on simple logistics. Waterford, like Haverford in South Wales, afforded a broad, sheltered estuary for ships to congregate; it was also the closest major Irish port to the west coast of England.

The king’s decision to move forward to South Wales and to choose Milford Haven as his first base of operations can be considered a bold, if necessary, military strategy. The king possessed a large army in Ireland that was well provisioned and substantial amounts of liquid capital to pay these troops for further military action. A longer time in Ireland would have given the king opportunity to gather more ships for the return voyage and wait for better weather, which would have been made for a large force on the ground in South Wales. The army in Ireland contained many of Richard’s staunchest supporters among the titled nobility and gentry. To move away from this base of military support could be dangerous. Yet, Richard II probably considered the move to South Wales to be worth the risk.

Some historians have criticized the king for not immediately advancing to Bristol, where apparently the duke of York was to meet him, and have interpreted this failure on the king’s part as an example of Richard’s timidity. But, a move to Bristol before possessing a good working knowledge of Henry’s intentions, the strength and state of his army, and his whereabouts would have been great folly. Moving to Bristol could have left Richard trapped by a siege or forced to withdraw by sea from Henry’s actions-both of which were politically unenviable options.

South Wales provided a substantial number of geographical, political and administrative advantages to the king. The roadstead at Milford Haven offered the largest and most sheltered port facility on the western coast of Wales and thus was an excellent location for ships with troops coming from Ireland to gather. The Haven also allowed Richard the strategic freedom to move easily forward by sea to Bristol or by land down the southern coast through the vale of Glamorgan, Chepstow, and across the Severn. A position in South Wales also offered the king the ability to move by land or sea to North Wales and the principality of Chester, where the Earl of Salisbury had been sent to raise the country for the king. Last and not least, a base in South Wales also afforded Richard an escape route by sea back to Ireland, Bordeaux, or to France, if such an eventuality became necessary.