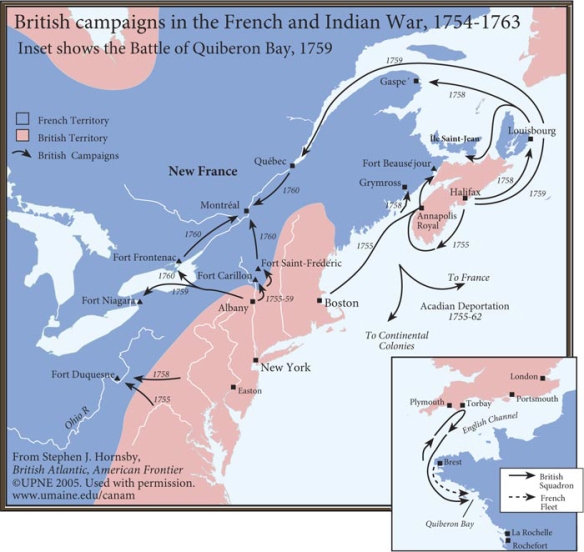

The most successful part of Braddock’s general plan was the capture of Forts Beauséjour and Gaspereau, controlling the isthmus of Chignecto as well as land access to Nova Scotia, and supporting the discontented among the 20,000 French Acadians who had been British subjects since 1714 but had never been required to take an unqualified oath of allegiance. British colonel Robert Monckton led 2,000 New England volunteers, raised by Governor Shirley of Massachusetts, and 270 British regulars from the Halifax garrison against stone Fort Beauséjour. Their flotilla landed without opposition and received traitorous assistance from within the garrison. The fort surrendered quickly; Fort Gaspereau capitulated without a shot being fired. This most successful part of the British offensive of 1755, and the only one that avoided wilderness marches, had been financed and led by the British, and manned largely by New England volunteers. Nova Scotia’s lieutenant governor Charles Lawrence (1709-60) added a cruel sequel to this easy victory. With an army at his disposal he decided to impose an unconditional oath of allegiance on the Acadians; Monckton’s forces supervised the expulsion of those who refused, constituting the majority of those Acadians who had not already fled to French protection.

The British offensive of 1755 had failed. Braddock’s army had been slaughtered, and Shirley and Johnson had not even reached the forts they were to besiege. The success in Nova Scotia might have suggested that colonial governors organize colonial armies to be led and paid for by the British. Instead, planners focused on explanations offered for the failures. Their response was to send more regulars, and to empower the new commander in chief, the earl of Loudoun (1705-82), with authority to override colonial political interference. They sentenced Loudoun and the British colonial war effort to two more years of wrangling and failure.

VAUDREUIL’S OFFENSIVE, 1755-1757

In 1755, governorship of New France came to Pierre- François de Rigaud, marquis de Vaudreuil (1698-1778), a Canadian born to an earlier governor, an officer in the troupes de la marine, and the former wartime governor of undersupplied Louisiana. Although addicted to reporting the successes of both Amerindians and French regulars as accomplishments of the Canadians, Vaudreuil understood how to mesh these three military traditions effectively. He took the initiative despite New France’s manpower disadvantage compared with the British North American colonies, which was in the neighborhood of 20 to 1. Vaudreuil used two methods: he supported Amerindian raids on the western frontiers of Pennsylvania and Virginia; and he captured major British colonial strongholds by a combination of guerrilla and regular warfare.

Fort Duquesne became the center from which dozens of raids were launched against the frontier settlements of the middle colonies. The French capitalized on Amerindian support that grew from the destruction of Braddock’s army, as warriors seized the opportunity to use the French in their own fight against encroaching British colonial settlement. The raids ensured that Virginia and Pennsylvania were preoccupied with building frontier forts, and contributing very little to attacks on French posts to their west or north. By 1758 Virginia was maintaining 27 wooden frontier forts, which could not prevent raids and which occasionally became targets themselves. Between 1755 and 1758 an estimated 2,000 British colonial settlers were killed in these raids, and even more were taken captive and adopted into Amerindian villages in the Ohio Valley. For Vaudreuil, a small investment in Canadian manpower and supplies supported raids that hobbled and distracted a richer opponent while strengthening Canada’s Amerindian alliances.

Vaudreuil combined irregular and regular warfare against his primary objective of 1756, Fort Oswego, the Lake Ontario base from which the English had threatened Fort Niagara the previous year and from which they could easily attack Fort Frontenac. Fort Oswego had begun, in 1728, as a trading post at the mouth of a river; as Anglo- French rivalry escalated, so did fortification. During the winter of 1755-56, Canadian scouting parties took prisoners and burned supply boats. In March a force of Canadians, mission Amerindians, and selected French regulars trekked 200 miles to attack and destroy Fort Bull, a supply depot at the crucial portage between the Mohawk and Oswego Rivers. The isolation of Fort Oswego was reinforced by attacks on supply boats on the Oswego River in July. The next month Fort Oswego was besieged by 1,300 French regulars, 1,500 Canadian militia, 260 Amerindians and 137 troupes de la marine. Louis-Joseph de Montcalm (1712-59), the newly arrived commander of the French regulars, led an attack that he hoped would last long enough to draw British regulars away from Albany, where they were a direct threat to New France. Weakened by preliminary irregular attacks, Fort Oswego surrendered within hours of the first cannonade from Montcalm’s guns. French forces took 1,520 men and 120 women and children prisoner, as was customary after a feeble defense. These prisoners proved particularly burdensome as Canada suffered another crop failure, delaying military operations the next year. Despite some tensions and the killing of at least 30 wounded prisoners by Amerindians after the surrender, the taking of Fort Oswego represented effective cooperation between Amerindian and European military methods.

Vaudreuil’s target for 1757 was more challenging. Fort William Henry was a substantial two-year-old, corner-bastioned earthen fort at the south end of Lake George, only one-third as far from Albany’s supplies and reinforcements as Fort Oswego had been. A major raid in March 1757 by 1,500 Canadians, Amerindians, and French regulars under Vaudreuil’s brother, François-Pierre de Rigaud de Vaudreuil, burned boats and outbuildings but failed to surprise or outmaneuver the garrison of 474 British regulars and colonial rangers. Interpreted variously then and since either as a successful spoiling raid or as a failed attempt to capture the fort, the raid contributed to the defensive posture of the British on that frontier in 1757. Canadian raids along the communications lines between Albany and Fort William Henry did not seriously disrupt supplies that spring.

Montcalm again led the summer attack with an army of nearly 8,000 regulars, troupes de la marine, Canadian militia, and mission Amerindians supplemented by 1,800 Amerindians recruited from the Great Lakes basin. Amerindian scouts completely defeated efforts by the fort’s commander, Lieutenant Colonel George Monro, to gather information about the approaching force. A frustrated Monro sent 350 men in whaleboats to scout down Lake George late on July 23, but they were surprised at dawn off Sabbath Day Point by nearly 600 Amerindians whose canoe attack allowed only about 100 to escape. This destruction of whaleboats ensured that Montcalm’s army would not be challenged on Lake George. Amerindians also prevented all British communication with the fort after the siege began. A well-conducted, European-style siege and defense ended with surrender of the fort on August 9.

Cooperation between regular and irregular warfare brought Canadian success, but it also brought an attack on prisoners of war the next day. Amerindians, deprived of promised loot because of generous surrender terms, attacked the column of 2,456 paroled prisoners and their dependents, killing at least 69. Amerindian disgust at what they saw as French collusion with the enemy, as well as the smallpox they carried back to their villages, ensured the end of this French advance into New York and reduced Amerindian support for New France thereafter.

Despite its successes, Vaudreuil’s aggressive defense of New France ended in 1757. Montcalm, who advocated withdrawal from the Ohio, Lake Ontario, and Lake Champlain frontiers and concentration on defense of Quebec and Montreal, was increasingly influential and openly at odds with Vaudreuil. The British and British colonists, who had been constrained by political, administrative, and strategic tangles during these three “years of defeat,” were about to put New France on the defensive.

PITT’S OFFENSIVE, 1758-1760

There was little strategic imagination in the British offensive that began in 1758; the targeting of Louisbourg, Fort Carillon, Fort Frontenac, and Fort Duquesne echoed the plan to reverse French “encroachments” in the undeclared war of 1755. The major difference was that three of four efforts failed in 1755, whereas three of four succeeded in 1758.

The resources available to British commanders were much larger in 1758, which cannot be said for their opponents. The relevant change in British politics was the appointment of William Pitt (1708-78) as secretary of state for the southern department and, effectively, as prime minister. Arrogant, eloquent, and ambitious, Pitt was disliked by cabinet colleagues and by King George II, but he worked efficiently in the revitalized ministry. Pitt represented patriotic nationalism in power, and he charmed voters, government suppliers, and creditors into a massive war effort. He was not winning a European war in America, as he claimed, or the reverse; Pitt raised and spent enough to support both wars. Pitt’s “subsidy plan” offered full reimbursement of all colonial assistance beyond levy money and pay for colonial troops. Soldiers, supplies, and transport became readily available from colonial sources anxious to earn sterling, while also winning a war.

British regulars, including about 10,000 recruits from America, constituted over half of the forces used in 1758, compared to one-seventh of the much smaller number employed in 1755. Regulars were retained over the winter for garrison duty and were ready for early spring campaigning, whereas colonial regiments were recruited for eight-month terms after annual legislative decisions, and were available only after spring planting. Colonial recruits into the regulars and colonial ranger units had a good reputation, and the latter became part of the regulars. Loudoun introduced light infantry units into all regular regiments, trained troops to counter ambushes, and organized an innovative army transport service that greatly assisted wilderness campaigning.

British naval resources also expanded markedly in those three years. British naval spending doubled to an unprecedented £4 million. The fleet included 98 ships-of-the- line to confront France’s 72. British fleets carried British regulars, gunpowder, and supplies to America as well as offering tactical mobility and additional manpower, especially for amphibious operations at Louisbourg and later at Quebec. The British naval blockade of French European ports was never complete, but there were no major “escapes” of substantial relief squadrons bound for America after 1757. Between early 1758 and late 1759 the French navy lost nearly half of its fighting strength, and by 1760 there were only 50 French ships-of-the-line to counter 107 British.

Louisbourg was to be the showpiece of the 1758 British offensive, an amphibious campaign uncomplicated by wilderness treks. Loudoun had brought a force of nearly 15,000 for the task the year before, but withdrew when he discovered that a fleet comparable to his own, and equally cautious, was in Louisbourg harbor. The 1758 landing was challenged by well-prepared shore entrenchments and by heavy seas, but not by a French fleet. A boatload of resourceful infantrymen were able to land in a protective “neck of rocks.” This minor weakness was exploited effectively by the British to gain control of the heights above, forcing defenders to retreat to the fort. Major General Jeffrey Amherst (1717-97) conducted a careful, thorough, but unimaginative siege that indicated the kind of leadership he would provide as commander in chief in subsequent campaigns. Thirteen thousand British regulars besieged the French, who were outnumbered three to one but led ably by Governor Augustin de Drucour (1703-62). Louisbourg surrendered after resisting for nearly two months, which was long enough to ensure that the British force could not proceed to Quebec that year.

Although Major General James Abercromby (1706-81) had become British commander in chief in North America, his major responsibility was the attack of Fort Carillon (Ticonderoga); the 1758 Louisbourg and Fort Duquesne campaigns were run from London as independent commands, and the Fort Frontenac expedition was initially canceled. Montcalm, very short of Amerindian scouts, was defending a vulnerable Fort Carillon with 3,500 men, opposing Abercromby’s nearly 15,000. Located to intercept waterborne traffic and to facilitate supply, the fort would have been untenable if cannon were mounted atop nearby Mount Defiance. Like Washington at Fort Necessity, Montcalm was not prepared to trust the fort’s ability to defend his men, and he had elaborate entrenchments prepared to intercept attackers. Trenches were reinforced by logs and sandbags and screened by a massive abattis, a tangle of freshly cut trees effective in slowing and disrupting advancing troop formations.

Abercromby’s attack of July 8, 1758, was precisely the type for which Montcalm had prepared. Abercromby, who is often considered criminally responsible for the resulting disaster, was in a hurry because of false information. French and Canadian prisoners had reported that Montcalm had 6,000 troops and that 3,000 more were expected to arrive soon with the talented and popular Chevalier François-Gaston Lévis (1719-87) at their head. Abercromby’s scouts atop Mount Defiance, where there were as yet no cannon, added to the urgency by reporting that Montcalm’s defenses were still incomplete but should be attacked quickly. The result was a poorly coordinated frontal assault on the entrenchments that continued long after it was clear that Abercromby’s scouts had been wrong. The French were never seriously threatened in a battle that killed 464 attackers. Montcalm’s victory against such impressive odds was also his victory over Vaudreuil. By the following February he would outrank Vaudreuil in military decisions, and would prepare Quebec for a defense like that of Fort Carillon.

Attempting to salvage something from this disaster, Abercromby authorized an expedition against Fort Frontenac. Lieutenant Colonel John Bradstreet (1714-74) took 3,500 American colonists in British pay on a surprise attack against a weakened Canadian outpost. The garrison of 70 surrendered on August 27, before the attackers had exhausted their 24-hour supply of ammunition for their cannons. Rather than a conquest, this success was a welltimed raid into enemy territory. The prisoners were released after promising the release of an equivalent number of prisoners held in Canada. The fort was burned, as was the French Lake Ontario fleet based there, after which the victors left.

The 1758 British campaign against Fort Duquesne was to avenge Braddock, but it also had strategic significance for Virginia and Pennsylvania, which were drawn more fully into the war. Brigadier General John Forbes (1710-59) supervised the methodical construction of a defensible 193-mile road, complete with stockades and forts no more than 40 miles apart. The route, west from Raystown (Bedford), Pennsylvania, was shorter, less susceptible to flooding, and traversed country with more forage than was available along Braddock’s road. Approximately 500 Cherokee and Catawba scouts initially accompanied the expedition, but left because progress seemed slow. Five thousand colonial militia and 1,840 regulars built Forbes’s road, giving Pennsylvania ready access to the Ohio country. On September 14 an advance party of 800 regulars and Virginia militia attempted to raid near Fort Duquesne, but were discovered and driven off after heavy losses. Fort Duquesne’s commander presumed that the English had been turned back, and reduced his forces to a winter footing. On November 24, when Forbes’s army advanced to within a day’s march of Fort Duquesne, it was evacuated and detonated. The English occupied the site of Fort Pitt (Pittsburgh) the next day.

A major diplomatic meeting at Easton, Pennsylvania, the previous month had been a promising omen for this campaign. Some 500 Amerindian leaders from 15 tribes met officials from Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and Forbes’s army. In return for assurances that certain fraudulent land sales would be canceled and that English presence in the Ohio Valley would be temporary, the Amerindians agreed to withdraw support from the French. Six days before Forbes reaches his objective, the British flag replaced the French one flying over the major Amerindian town of Kuskuski.

The campaigns of 1758 demonstrate that fortune favors the biggest armies and navies. France was unable to reinforce a New France that had mobilized all adult males without mustering more than 16,000 militia, regulars, and troupes de la marine. Their opponents had increased their troops in the field to more than 44,000 in 1758. The shrinking of New France was obvious from the burned forts and lost Amerindian allies in the west. British conquest of Louisbourg was strategically more ominous as a base from which all Canadian maritime traffic could be challenged and an army launched against Quebec. As a pessimistic Montcalm predicted, New France would fall in one or two campaigns unless peace was made in Europe.