PRINCIPAL COMBATANTS: British and British-American colonists, and some Indian tribes vs. French and French- Canadian colonists, and numerous Indian societies including the Abenaki, Cherokee, Delaware, and the mission Indians of New France

PRINCIPAL THEATER(S): Upper Ohio Valley, New York, Nova Scotia, Canada, Carolinas

MAJOR ISSUES AND OBJECTIVES: Anglo-French colonial border disputes provoked imperial intervention and coalesced with a European and global conflict over territory and trade. Indian societies allied with New France sought to reverse and avenge British colonial encroachment on their lands.

OUTCOME: Britain conquered New France; Europe accepted British claims to all of North America east of the Mississippi River, bringing an Indian war of resistance, 1763-65; British colonists resisted and revolted, because of imperial taxation to cover some costs associated with this war.

APPROXIMATE MAXIMUM NUMBER OF MEN UNDER ARMS: British: more than 25,000 British-American volunteers and militia, 34,000 British regulars, and fewer than 1,000 Amerindian allies. French: 8,000 Canadian militia, 5,600 French regulars, fewer than 3,000 troupes de la marine, and more than 4,000 Amerindian allies

CASUALTIES: British imperial and colonial, 5,758; French imperial and colonial, 2,025; Amerindian, 317

TREATIES: Treaty of Paris (February 10, 1763)

As the climactic resolution to an Anglo-French struggle for dominance in North America, the French and Indian War was rooted in a century and a half of intercolonial rivalry that extended from the fur outposts of Hudson Bay to the plantations of Louisiana and the West Indies. This war was also part of two other, even longer struggles that would not be resolved in 1763. One was between Amerindian societies and the European colonists who invaded their hunting and farm lands. With widespread Amerindian adoption of the flintlock musket in hunting and warfare, sustained Amerindian resistance came to require a reliable European supplier of guns and gunpowder. New France, less populated and more dependent upon the fur trade than the British colonies, was widely preferred as an ally. Strengthening this weaker European contender helped continue a struggle that Amerindians had every reason to prolong. The other epic struggle in which this war was a major episode was the Anglo-French contest in Europe and overseas. Unprecedented British and French imperial commitment of ships, troops, and money drew the North American conflict into a European (SEVEN YEARS’ WAR) and global clash as never before. The “French and Indian War” was a British colonial term still used to describe the North American theater of that conflict. The war that began at the forks of the Ohio River came to include battles and sieges as far apart as Prague, Quebec, Havana, and Manila, followed by elaborate peace negotiations in Paris.

OHIO ORIGINS

The upper Ohio Valley had been marginal in the half-century of intense Anglo-French commercial rivalry before 1740. Denuded of valuable furs and far from major Canadian routes to the Mississippi Valley, this intertribal hunting ground had become home to Shawnee, Delaware, and Mingo migrants from farther east. During the War of the AUSTRIAN SUCCESSION (called “KING GEORGE’S WAR” by British colonists), Pennsylvania traders began exploiting the wartime shortage of French trade goods in this area, and supporting an anti-French “Indian Conspiracy of 1747.” That same year, Virginia land speculators organized the Ohio Company of Virginia, the first of several competing companies eager to appropriate land.

New France responded with an armed diplomatic tour of the upper Ohio Valley in 1749 under Pierre-Joseph Céleron de Blainville (1693-1759), who expelled British traders and left lead plates proclaiming French sovereignty. However, he met open hostility in councils held with Seneca, Delaware, Mingo, Shawnee, and Miami leaders. Miami chief Memeskia of Pickawillany, a new and well-positioned Miami trading town that was pro-English, was particularly outspoken. Blainville lacked the troops to disrupt Pickawillany, but in June of 1752 some 240 Ottawa and Ojibwa looted the storehouses, captured three British traders, and killed and ate chief Memeskia. Amerindians noticed that the distraught Miami received no help from their Six Nations or Pennsylvanian allies. The next year Canadian governor Michel-Ange Duquesne de Menneville (1702-78) sent 1,500 men to construct three forts between Lake Erie and the forks of the Ohio River. Veteran Canadian explorer, interpreter, and soldier Jacques le Gardeur de Saint-Pierre (1701-55) commanded new Fort Le Boeuf that fall and politely refused a request by the Ohio Company to leave. The message was delivered by George Washington (1732-99), a young Virginia militia officer, surveyor, planter, and Ohio Company stockholder.

The Ohio contest became bloody early in the summer of 1754. Having secured formal British permission to use force to oust the French, Lieutenant Governor Robert Dinwiddie (1693-1770) of Virginia raised a new 159-man Virginia Regiment of the destitute and the drafted whom Washington led toward the forks of the Ohio River. On May 28 they ambushed a Canadian reconnaissance party, capturing 21 and killing 10, including ensign Joseph Coulon de Villiers de Jumonville. This peacetime “assassination of Jumonville” eventually became a European diplomatic incident; more immediately it prompted retaliation by some 500 French, Canadians, and mission Amerindians led by Jumonville’s brother.

Aside from the ambush, Washington’s tactics were conventional. He took his recruits back to a small improvised stockade, aptly named Fort Necessity, which they attempted to strengthen with trenches and firepits. This venturesome defense was abandoned as soon as war whoops were heard from the woods. Defense from within the palisade also proved hopeless, and Washington surrendered on July 3, 1754, on honorable terms. There was, and is, dispute over whether Washington understood the clause in the French surrender terms by which he acknowledged assassinating Jumonville. Aside from two hostages who were supposed to ensure the return of prisoners taken in the Jumonville incident, the Virginians were released. The “conquest” of a pathetic little “fort” was seen by the British as an act of war.

The Virginians, who had long been geographically insulated from intercolonial war, had instigated a conflict they could not sustain alone. South Carolinians resented Virginian attempts to recruit Creek and Catawba warriors; Pennsylvanians were opposed to the Virginian initiative that immediately put their own traders and frontier settlers at risk and alienated the Delaware friends of the Quaker-led colony. That summer, seven British colonies north of Virginia had legates at the Albany Conference, called to organize intercolonial defense and to placate disgruntled Six Nations allies, though it is best remembered for theoretical discussions of colonial unity that masked a failure to agree on defense quotas.

It was the British government that responded in support of Virginia, backing its most valued and populous North American colony. The duke of Newcastle was central to a British ministry that did not want war and believed, rightly, that the French felt the same. With the arrival of news of the fall of Fort Necessity and the French building of Fort Duquesne, British commitment escalated. What had been a promise of £13,000 and the use of three companies of regulars already in America grew into a more ambitious proposal, supported by William Augustus, duke of Cumberland (1721-63), favorite son of King George II (1683-1760) and captain-general of the British army. By the end of 1754, two understrength Irish regiments had been sent to America commanded by Major General Edward Braddock (1695-1755) of Cumberland’s own elite regiment, the Coldstream Guards.

The French government was not ready for war and, with 10 times Britain’s army but only half its navy, would have preferred to fight in Europe. Nonetheless, France sent six regular regiments to reinforce Louisbourg and Canada in 1755. Despite the peace, a 19-vessel British naval squadron was instructed to intercept this troop convoy off Newfoundland; they captured only two unsuspecting French ships containing 10 companies of regulars.

BRADDOCK’S CAMPAIGN, 1755

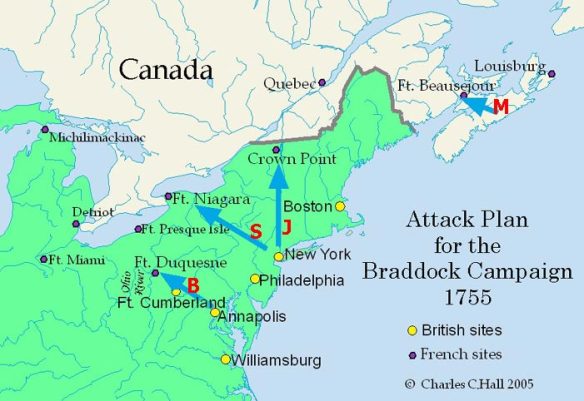

The British government intended to use Braddock’s regulars and colonial support to counter four French “encroachments” on British-claimed territory along the disputed borderlands in North America. Braddock was to proceed against Fort Duquesne, then take Forts Niagara, St. Frédéric, and Beauséjour, with the possibility of a negotiated settlement between sieges. This ambitious and rather disparate strategy, designed for an undeclared war, would be imprinted upon subsequent British planning. Meeting with colonial governors in Alexandria, Virginia, in April 1755, Braddock learned of military preparations in New England, under Massachusetts governor William Shirley, that were impressive enough to warrant a change of plans; simultaneous attacks were to be made on all four targets. Four armies, each of different composition but each assigned to take one fort, set off on what could have been an experiment in methods of fighting and funding war in North America.

Braddock personally commanded the Fort Duquesne expedition in the face of major transport shortages, minimal Amerindian support, and mountainous terrain that should have prevented movement of his heavy artillery. However, his army moved efficiently over the 150 miles from Alexandria to Little Meadows. Braddock than led an advance force of 1,450 that marched without incident for three weeks, reaching the Monongahela River on July 8. The vanguards apparently lulled into overlooking routine precautions, failed to detect an approaching force of 783 French, Canadians, and Indians. The equally surprised company of troupes de la marine, recruited in France and officered by Canadians, blocked the 12-foot-wide forest roadway with effective conventional musketry. Braddock’s column either did not receive, or did not hear, the order to halt: infantry, artillery, and baggage train telescoped into each other in confusion. Amerindians and Canadians immediately used Amerindian tactics of “moving fire” along both flanks of the disrupted column. The British lost 977 wounded and killed, including Braddock, whereas their opponents sustained only 39 casualties. There is dispute over Braddock’s personal responsibility, but he came to bear the opprobrium accompanying a stunning defeat, one that encouraged Amerindians to join the French.

William Shirley, the lawyer and politician who had prepared thoroughly for a New England campaign in Acadia and against Fort St. Frédéric, took personal charge of an attack on Fort Niagara instead. This campaign, launched from Albany by a governor of Massachusetts, met predictable political interference from New York’s lieutenant governor James De Lancey (1703-60), whose connections were bypassed in awarding supply contracts. Because a second army, bound for Fort St. Frédéric, was also in Albany competing for supplies, cannon, wagons, whaleboats, workmen, and Six-Nation support, there were severe delays even before Shirley faced the tasks of navigating the Oswego River and building a fleet on Lake Ontario. The revived Shirley and Pepperrell regiments of British regulars recruited 2,500 colonists, joined by 500 New Jersey volunteers and 100 Iroquois, who all set out on this venture that stalled at Fort Oswego. Shirley, who became commander in chief after Braddock’s death, was easily discredited by his political opponents.

The attack on Fort St. Frédéric was even more colonial, consisting of 3,500 volunteers who were paid, supplied, and ultimately controlled by colonial assemblies. William Johnson (1715-74), Irish pioneer, adopted Mohawk chief, and former fur trader, was in charge of a force supplemented by 300 members of the Six Nations. Although the force’s composition might suggest irregular warfare, the conventional assignment was to cut a road and haul 16 heavy cannon to besiege a stone fort. By early September they were still 50 miles from their objective, but had built Fort Edward on the upper Hudson and had cut a 16-mile road to Lac St. Sacrament, which they prematurely renamed Lake George.

A force of 700 French regulars, 300 troupes de la marine, 1,300 Canadian militia, and 700 Amerindians had been sent in mid-August to stop Johnson. Newly arrived Jean-Armand, Baron de Dieskau (1701-67), who had fought with irregulars in Europe even before becoming a protégé of Maréchal de Saxe (1696-1750), led them boldly. With an advance force of Amerindians and selected regulars and militia, Dieskau intended to surprise still-unfinished Fort Edward, isolating Johnson’s army from its supplies and its retreat route. However, the Caughnawaga Iroquois with him flatly refused to attack Fort Edward. Adapting his strategy effectively, Dieskau led his force along Johnson’s new road to attack his camp at the other end. Learning that a contingent of Johnson’s army was coming down that road, Dieskau agreed to an elaborate ambush that killed 90, including 40 Mohawk, and sent the survivors racing for Johnson’s camp. Dieskau wanted his troops to give chase, but the Amerindians declined to attack a camp fortified with four functional cannon behind a barricade of overturned wagons and whaleboats. Foiled again, Dieskau organized what proved an impressive, though futile, display of conventional valor. His regular grenadiers, arranged in a narrow column, attempted a bayonet charge to take the guns. They failed against massive musket fire from barricaded British-American militia and cannon fire supervised well by Johnson’s only regular officer, Captain William Eyre. However, the successful defenders were severely shaken and showed little interest in pursuing the defeated French. Johnson’s army had won the Battle of Lake George and captured the injured Dieskau, but were shocked by the level of casualties on both sides and refused to proceed to Fort St. Frédéric. Instead, they built Fort William Henry, a substantial fort necessary to challenge French access to a road that could now lead French invaders south more rapidly than it had allowed its English builders to go north.