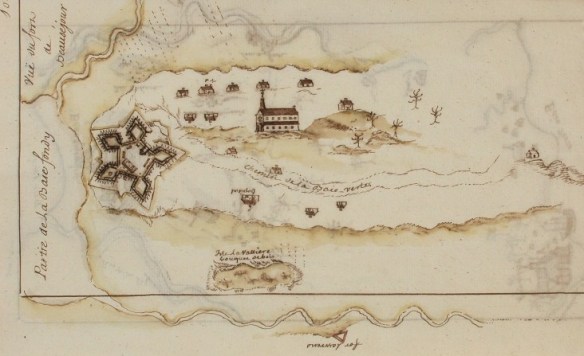

Fort Beauséjour and Cathedral (c.1755)

Fort Beauséjour, Spring 1754.© Parks Canada / L. Parker

Fort Beauséjour, Spring 1756 © Parks Canada / L. Parker

The main event of King George’s War 1744-1748 (in Europe the struggle for of Austrian Succession) was the capture of Louisbourg. Under the terms of the Treaty of Aix la Chapelle that ended the war, Louisbourg was returned to France, and Britain’s ownership of the peninsula of Acadia (Nova Scotia) was confirmed. In 1749 Britain started building her great naval base at Halifax and began bringing in settlers. France hoped that the part of Acadia which is now New Brunswick would be retained as French territory.

To limit British expansion and to hold the land north of the Bay of Fundy as well as protect the remaining Acadian settlements, France began building Fort Beauséjour in 1751. The fort was pentagon-shaped, with five bastions. These, the casements in the curtain wall, and the other buildings, were of timber. The main structure was reinforced with a ditch and elevated slope, or glacis. It was strategically placed on the west side of the Missaguash River, overlooking the Bay of Fundy and the Tkntramar Marshes, part of which had already been drained because in establishing farms, the Acadians preferred draining marshland to clearing forests. At the other end of the Isthmus of Chigneeto, the French built Fort Gaspereau as a supply base to Beauséjour. Gaspereau stood on the shore of Baie Verte (near the site of Port Elgin). It lay on the more direct route linking the French posts in Acadia with Ile Saint Jean (Prince Edward Island), Louisbourg, and Quebec – the latter two, the source of garrisons and supplies.

To reinforce her ownership, France encouraged her former Acadian subjects to move from the lands under British control and resettle around Beauséjour. Some did come from Beaubassin, Nappan, and Macan.

Many other Acadians preferred to remain in their original settlements but refused to take an unconditional oath of allegiance to Britain. They really wanted to remain neutral and to avoid being disloyal to either power.

Before the French started Fort Beauséjour, the British had built Fort Lawrence on the south side of the Missaguash River, and a scant three kilometres away. The Missaguash became an unofficial boundary between the disputed territory occupied by the French and British Nova Scotia. The British fort was named for Charles Lawrence, the lieutenant governor who by 1755 had succeeded the first governor, Edward Cornwallis.

Residing at Fort Beauséjour in 1755 were the commandant, Jean-Baptiste Mutigny de Vassan and a few colonial regulars, most of them troupes de la marine. Also on hand was the soldier-priest of the Spiritan order, the Abbé Jean Le Loutre. He was notorious among the British settlers for inciting his Micmac converts to attack their homes.

In command at Fort Lawrence in 1752 and 1753 was the man who would lead the expedition against Beauséjour in 1755 – Lieutenant-Colonel Robert Monckton, then of the 47th Regiment of Foot. He maintained communications with Beauséjour, for the records show he exchanged notes, deserters and runaway horses with Beauséjour’s commandant, Vassan. In 1753, he moved to Halifax, and early in 1755, when hostilities between France and Britain were increasing, he was in Boston planning his expedition.

Matters were coming to a head between Britain and France. The main issue was the ownership of the Ohio Valley. British colonists wanted room to expand. France wanted to keep open a line of communication to the Mississippi and Louisiana. Protecting the route was Fort Duquesne (the site of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania). In the spring, a large expedition led by Major-General Edward Braddock had been sent against the fort.

Assisting Monckton in Boston was the governor of Massachusetts, William Shirley. From New England, Monckton would take two battalions of provincial troops, some 2,000 men, commanded by Lieutenant-Colonels John Winslow and George Scott. Monckton planned to rendezvous in the Annapolis Basin with some British regulars, many of them artillerymen, from Halifax. The number of regulars on the expedition was 270, but some were from the Fort Lawrence garrison.

In the thirty-one vessel flotilla that sailed from Boston were the twenty-gun frigate Success with Lieutenant-Colonel Winslow aboard, the schooner Lawrence carrying Lieutenant-Colonel Monckton, two other frigates, some snows, sloops, brigantines and schooners. This fleet arrived off Annapolis on 25 May. Within five days it had been joined by the sloop Vulture and six small troop transports bringing the regulars from Halifax. The combined fleet sailed on 1 June and lay near the mouth of the Missaguash River the following day. At about 6.00 p.m. Monckton began landing troops and two 6-pounder cannon on the east side of the river. The troops marched to Fort Lawrence, which would serve as a base and as cover. Monckton had acted with speed but the French were not taken by surprise for they had seen the fleet as it approached.

The commandant of Beauséjour at the time was Louis Du Pont Duchambon de Vergor, an unpleasant debauched character, and a friend of the equally debauched Intendant Bigot. Vergor’s garrison was 175 colonial regulars from troupes de la marine, Le Loutre and his Micmac followers, and such Acadians as could be coerced into serving. About 1,200 to 1,500 Acadians lived in the neighbourhood, and Vergor embodied 300 of them from his militia. Vergor was an incompetent soldier, but he had courage, and he did manage to have his men destroy a bridge – Pont à Bout – over the Missaguash, and to break dikes and flood some land to impede the progress of Monckton’s force.

Some of Vergor’s garrison were in a redoubt near Point de Bute close to the destroyed bridge, and there the first encounter took place, apart from a little skirmishing by scouts and Indians. The French in the redoubt opened fire with cannon and muskets. Monckton’s two 6-pounders replied. After a quarter of an hour the French set fire to the redoubt and to some houses, to prevent the British using them as cover, and withdrew into Fort Beauséjour.

For the next few days little happened other than lively skirmishing. A British sergeant and ten privates were killed, while the French lost three soldiers and one Indian killed. In the meantime Monckton and his officers were reconnoitering the locality. The logical approach was from the northeast. A ridge ran inland from Beauséjour that was roughly parallel to the Missaguash River. By placing guns there, Monckton could get them within range to pound the fort. He decided to move two more guns to that position, and to march his men up the east side of the Missaguash, crossing over well above Beauséjour, and attaining the ridge in the vicinity of Aulac. From there he could move his guns forward. Most of the troops would be used to encircle the fort, and the men would dig siege trenches for protection. All this took time, because the French fired on his positions, which meant entrenchments at every advance. His guns were not ready to begin firing on the fort until 13 June, by which time he had not encircled Beauséjour completely.

The firing had a demoralizing effect on the garrison inside Beauséjour. On the 16th, before Monckton was ready to begin the siege in earnest, – his entrenchments still incomplete – Vergor sent him an offer of surrender. Abbé Le Loutre, fearful of capture after the activities of his Micmacs, slipped away, through the woods to set out for Quebec. Monckton agreed to allow the Beauséjour garrison passage to Louisbourg and he pardoned the Acadian irregulars who had been pressed into service by Vergor, pending instructions from Halifax. By that time Lieutenant-Colonel Winslow, at the head of part of his battalion, was marching for Fort Gaspereau. On the 17th or 18th, Benjamin Rouer de Villeray, the commandant of Fort Gaspereau, accepted the same terms as Vergor, and did not offer Winslow any resistance.

Monckton had accomplished his task in less time and with fewer losses than he had anticipated. With the manpower at his disposal, he began repairing and enlarging Fort Beauséjour, now renamed Fort Cumberland in honour of the commander-in-chief of the British army. Monckton soon received a distasteful order from Governor Charles Lawrence. Some representatives of the Acadian people had been meeting with Lawrence in Halifax, and as they had always done, refused to take the unconditional oath of allegiance. Lawrence decided that the time had come to use military power to expel the Acadians. He ordered Monckton to carry out the expulsion in the Chignecto area, to punish them for taking up arms; they were not permitted the opportunity to take the oath of allegiance. Although he disapproved, Monckton set about the task efficiently, arresting Acadians, sending sodiers to burn their villages, and supervising the deportation of about 1,100 unfortunates.

Abbé Le Loutre, who had been one of the causes of trouble for the British in Nova Scotia, succeeded in reaching Quebec. On 15 September he sailed for France. His ship was captured by a British squadron and he was held prisoner for eight years. Not until the peace treaty was signed in 1763 was he released.

Beauséjour was the only British success of 1755, the year before the Seven Years’ War officially began. Braddock’s attempt to capture Fort Duquesne ended in disaster and his death. Monckton continued serving efficiently. As the colonel-commandant of the 2nd battalion, 60th Royal American Regiment, he later stood on the Plains of Abraham as James Wolfe’s senior brigadier-general.