Lake Naroch Offensive (1916)

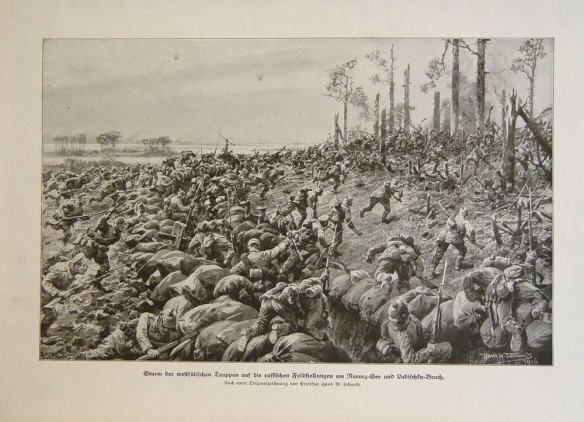

The last real effort by the old Russian army—as distinct from the new, which emerged in summer 1916 on Brusilov’s front—was the offensive staged at Lake Narotch in March 1916. It was an affair that summed up all that was most wrong with the army. There had been talk of a spring offensive for some time—Stavka had felt that the results of Sventsiany in September 1915 justified a renewal of the offensive in this region; and the French were even told that it could well win the war outright. Now, the bulk of German troops had gone against France, had lost heavily at Verdun. Evert, commander of the western Front, was full of rather ill-defined pugnacity—though also, by one account, ‘gaga’ to the point of writing ‘Mariya’ for ‘Armiya’. Moreover, the French had been told, in December, that if one ally was attacked, the others must launch immediate offensives to save it—an argument designed to save the Russian army from the isolation of summer 1915, and now turned against Russia. French appeals for help went out as soon as the German offensive began at Verdun. Alexeyev could not refuse his help. Stavka was now prisoner of its own arguments. Alexeyev had told Zhilinski to suggest that Russia was now strong enough to attack. Privately, he did not feel this at all—there had been delays in the re-organisation, and the army, now counting 1,700,000 men at the front—with 1,250,000 rifles—was not yet strong enough for offensive action. Evert, too, began to quail at the thought of attack once he was asked to bring his pugnacity to some concrete expression—no doubt he had, in the interim, read the south-western commanders’ reports on the failure of their winter offensive, where a thousand guns with a thousand rounds each, and two-fold superiority of numbers, had failed to make much of a dent in the Austro-Hungarian lines. But not much could be done: an offensive would have to be staged for the benefit of the French. On 24th February—three days after the Germans launched their attack on Verdun—there was a conference in Stavka. The Russian superiority of numbers was now considerable—on the northern front, 300,000 to 180,000; on the western, 700,000 to 360,000 (917 battalions to 382) with 526 cavalry squadrons to 144; and on the south-western front, about half a million men on either side (684 Russian battalions to 592, and 492 squadrons to 239).

It was felt that the western front—Evert’s—should attack. The shell-reserve had now been built up to 1,250 rounds for the 5,000 field guns, 540 for the 585 field-howitzers, and 685 rounds each for nearly a thousand guns—a force that, if concentrated, must surely bring great results. It would be Evert’s duty to ensure concentration of this force. There were also, now, increasingly, rises in the number of battalions and divisions, of which there were 152 in March, 163½ in summer, with forty-seven cavalry divisions, later fifty. The area of attack18 was much the same as in September 1915—east of Vilna. The two army groups, Kuropatkin’s and Evert’s, must co-operate in attacking, one to the south-west against Vilna, the other due west from the line of lakes east of Vilna. The Russians’ superiority was a considerable one—II Army, on the line of lakes, assembled 253 battalions and 233 squadrons of cavalry, over 350,000 men, with 605 light and 282 heavy guns—982 in all if two corps in reserve are included. There were ten army corps involved, over twenty divisions. The German X Army, here, had four and a half infantry divisions, subsequently built up to seven: 75,000 men, with 300 guns, subsequently built up to 440. It is, in the first place, notable enough that the Russian superiority at Lake Narotch—in men, guns, and shell (since each gun had a thousand rounds and more) was considerably greater than had been the Germans’ superiority in May 1915 at Gorlice, or even in July 1915 on the Narev.

The difficulties came, as usual, with command and operations. In the first place, the promised co-operation of Kuropatkin’s front did not come into much effect, beyond a feeble demonstration at Dvinsk that cost 15,000 men. II Army was commanded by General Smirnov, born in 1849, ‘a soft old man with no distinction of any kind’. Usually, he played patience while Evert’s chief of staff did the work; Evert, himself elderly, resisted attempts to have him dismissed by reason of age; and he was removed from command only just before the attack, to be replaced by the younger Ragoza—a man altogether unfamiliar with II Army, and subsequently replaced in turn by Smirnov. The corps were drawn up in groups, each commanded by the commander of one of the corps involved—as usual, on principles of seniority. In this case, the groups were taken by Pleshkov, Sirelius, Baluyev. Of Sirelius, Alexeyev wrote, ‘It seems unlikely that he will be able to manage the bold and connected offensive action or the systematic execution of a plan that are needed.’ But attempts to remove Sirelius broke down because, it is alleged, ‘some old granny still has flutterings about the heart when his name comes up’.

The offensive was carried out at a time of the year that could not have been less suitable if it had been chosen by the Germans. It opened on 18th March. The winter conditions had given way to those of early spring—alternating freezes and thaws that made the roads either an ice-rink or a morass. Shell would explode to little effect against ground that was either hard as iron or churned to a morass; gas was also ineffective in the cold. Supplies presented problems that the best-trained army would have found impossible to solve: the man-handling of boxes of heavy shell through slush that was a foot deep. The Russian rear was a scene of epic confusion—complicated by the astonishingly large masses of cavalry deployed there, to no effect whatsoever at the front. It was altogether an episode that suggests commanders had lost such wits as they still possessed. Preparations had gone on for some time, or so Evert alleged. In practice, the Russians’ positions were sketchy—some parts of their line were protected only by staves in the ground, and Kondratovitch, who inspected II Army’s positions, said that, when snow fell, rifle-fire became impossible. 20.Corps was sited in a marshy region, with its rear in full view of German artillery. There had been almost no preparation of dug-outs—nor, in view of the season, could there be. But the elderly commanders, their mental digestions still coping uneasily with the lessons of 1915, were in no condition to think things out. The Germans received a fortnight’s warning of the offensive—it was even discussed by the cooks in Evert’s headquarters three weeks before it began.

The attack began with bombardment on 18th March, the northernmost of the corps groups—Pleshkov’s—leading off. Of all bombardments in the First World War, this was—with strong competition—the most futile. It was subsequently known as ‘General Pleshkov’s son et lumière’. A subsequent investigation of the artillery-affairs in this battle revealed that only in Baluyev’s group had there been discussion between senior artillery and infantry officers on the ground—as distinct from maps—as to how things should go. Almost no reconnaissance had been conducted, so that the guns fired blind—on Pleshkov’s front, they were even told to fire blind into a wood, behind which the Germans were thought to be. On Sirelius’s front, the guns registered on their own infantry’s trenches, in case the Germans came to occupy them. The guns were useless against German enfilading-positions and communications-trenches, since no-one knew with any accuracy where they were; even observation-posts for the guns were, as things turned out, vulnerable to machine-gun fire. It was only on 7th March that Pleshkov’s artillery was told what to do, and the instructions were changed on 13th March, the guns having to be hauled over marsh and slush to new positions. A further peculiarity was that artillery was divided into light and heavy groups: the heavy artillery of Pleshkov’s group was mainly concentrated in the hands of Zakutovski, the light artillery mainly in the hands of Prince Masalski, corps artillery commander. The two men quarrelled—Zakutovski believing that, as commander of the whole group’s artillery, he should be giving the orders, while Masalski reckoned that, being commander of artillery in the corps mainly involved (1.), he should have the task. There was almost no co-operation between the two men; and shell-delivery became difficult enough, since heavy rounds would be delivered to Masalski, light ones to Zakutovski, and not released by them—even if the morass had allowed it. One Corps (1st Siberian) got half the shell it needed; another (1st) twice as much as it could use. This was more than a battle of competence. It reflected the poor state of relations between infantrymen and gunners, Masalski protecting the one, and Zakutovski the other. In this way, many gunners’ tasks were not carried out at all, and many duplicated. Light artillery tried to do the work of heavy, heavy of light.

Pleshkov had supposed that a narrow concentration of guns—on two kilometres of his twenty-kilometre sector—would create a break-through. His guns fired off their 200 rounds per day, commanders feeling that a weight like this—after all, equivalent to three months’ use of shell, as foreseen in 1914—could not go wrong. With four army corps on a front of twenty kilometres, against a German infantry division with one cavalry division, there ought not, in commanders’ view, to be any difficulty. By sending in waves of infantry on two kilometres, Pleshkov merely gave the German artillery a magnificent target; and when, as happened, these occupied German trenches, they would be fired on from three sides by German guns on the sides of the salient—guns that had been registered previously on the trenches, which were found evacuated. One division attacked before the other, because of an error in telephone-messages; it even attacked, on 18th March, under its own bombardment, no doubt because liaison between Zakutovski and Masalski was so poor. A further corps assaulted the woods of Postawy, also in vain—German guns being concealed by the woods. In all, Pleshkov’s group lost 15,000 men in the first eight hours of this offensive—three-quarters of the infantry mustered for attack, although fifteen per cent of Pleshkov’s total force. On 19th March the attacks were continued, although trenches now filled with water as rain came, with a thaw. There were minor tactical successes—600 prisoners being taken—and losses of 5,000 in a few hours, equivalent to a whole brigade. On 21st March Pleshkov tried again, and even Kuropatkin stumbled forward. Each lost 10,000. In the rear, confusion—brought about mainly by the presence of 233 cavalry squadrons, who monopolised supplies and transport—was of crisis proportions, the hospital-trains breaking down, troops going hungry while meat rotted in depots. Over half of all orders were countermanded.

The only success of any dimensions came on Baluyev’s front, on Lake Narotch, where artillery and infantry had co-operated. At dawn on 21st March Baluyev attacked along the shores of Lake Narotch, using the ice, and helped by thick fog. His gunners sustained an artillery duel with the Germans, and a few square miles were taken, with some thousand prisoners. Sirelius, to the north, would not help at all, relapsing into cabbalistic utterance, and losing only one per cent of his force—through frost-bite. In the next few days, there were repeated attempts by Baluyev and Pleshkov; then the affair settled down to an artillery-duel. Later on, in April, the Germans took what they had lost. In all, they had had to move three divisions to face this attack, ostensibly, of 350,000 Russians. Not one of these came from the western front. The Russian army lost 100,000 men in this engagement—as well as 12,000 men who died of frostbite. The Germans claimed to have lifted 5,000 corpses from their wire. They themselves lost 20,000 men.

Lake Narotch was, despite appearances, one of the decisive battles of the First World War. It condemned most of the Russian army to passivity. Generals supposed that, if 350,000 men and a thousand guns, with ‘mountains’ of shell to use, had failed, then the task was impossible—unless there were extraordinary quantities of shell. Alexeyev himself made this point to Zhilinski, saying that the French Army itself demanded 4,200 rounds per light gun, and 600 per heavy gun, before they would consider an offensive, and Russia had not these quantities. In practice, even Russia could have assembled such quantities on a given area of front had the generals managed their reserves properly. But they had no way of arranging sacrifices by one part of the front to the benefit of another; they did not understand the tactical problems; and, certainly, recognition of the extreme incompetence with which affairs had been combined in March, 1916 remained platonic. As before, artillery and infantry blamed each other, the only positive consequence being a demand for yet more shell. The way was open to Upart’s demand for 4,500,000 rounds per month, and also to the eighteen million shells that were stock-piled, to no effect save, in the end, to enable the Bolsheviks to fight the Civil War. Now the western and northern army groups would have no stomach for attack. It was only the emergence of a general whose common-sense amounted to brilliance, and who selected a group of staff-officers who were almost a kernel of the Red Army, that gave the Russian army a great rôle in 1916.