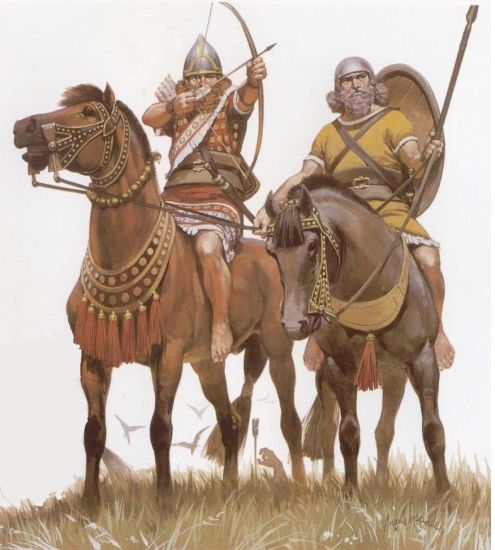

Cavalry first served in the Assyrian army under Tukulti-Ninurta III. Those illustrated date from the reign of Ashurnasirpal, and show how the cavalry still employed the ‘donkey seat’ when riding the horse. Tactical employment of this period shows how, by riding in pairs, they were envisaged as ‘charioteers without their chariot’. As in the chariot, the warrior is the superior soldier, as can seen by his dress. The ‘squire’ wears a simple iron skullcap, which in the reign of Shalmaneser III had been replaced with an iron conical helmet of the type worn by the archer.

Depicted here are Assyrian horse lancers of the reign of Sargon II, on campaign against Urartu in 714 BC. There are the soldiers Sargon employed straight off the march in the battle that defeated the Urartian army to the ast of Lake Urmia. Those illustrated clearly attest to the much greater proficiency of the Assyrian cavalry arm by this date. The armament is heavier, with both troopers equipped with the compound bow, quiver, and long stabbing lance. The cavalry are now equipped with footwear in the form of socks with lace-up boots.

This a horse lancer, and illustrates the final appearance of cavalry before Assyria’s demise. The horse is now almost fully covered by fabric armour, while in essence the trooper is little different to that in [the above illustration from Sennacherib’s reign]

Heavy armour was generally a characteristic of shock cavalry that intended to close with the enemy, cavalry relying upon missile weapons tending to be more lightly armoured. Nevertheless, even the crews of light two-man chariots, where the only offensive weapon was the bow, are sometimes depicted wearing scale body armour. The reason behind this was that armour required a trade-off between balance and protection. For a charioteer, balance was not too much of a problem and so the more protection the better, being as helpful in warding off enemy arrows and sling stones as blows from hand weapons. By contrast, for a horseman balance and ease of movement was much more of an issue, so the trade-off only really became worthwhile when he was intending to indulge in shock combat where such protection was obviously a massive benefit. One of the benefits that stirrups would bring much later was that they made it easier to shift weight and correct balance, compensating for, or allowing, the top-heaviness of heavier body armour. There was also the issue of the weight carried by the horse. Although horses were strong enough to be ridden, any animal can pull much more weight than it can carry (that was the whole point of the wheel). Increasing the weight of the rider starts to have a detrimental effect on a ridden horse’s speed and endurance sooner than on a driven one.

In many Near Eastern armies the horses themselves might also be armoured with trappers that covered their chests, shoulders, backs and flanks, just as modern horse rugs do. These could be of thick felt or hair and called a parashshamu, with a neckpiece, or milu, of the same material; or these could be of scale, when it was called a sariam as for human armour. Most early ridden cavalry horses, however, were not armoured, horse armour gradually becoming more common again over the course of several centuries. Horses in heavy work can overheat easily, and in severe cases this can lead them to ‘tie up’, becoming effectively paralysed, and even leading to their death. That expensive horses were exposed to this risk by the addition of armour suggests they were expected to be right in the thick of battle. The burden of armour would have reduced the horse’s endurance. It was therefore more useful to units called upon for one or two short, but potentially decisive, charges than those used in the continuous manoeuvring of skirmishing.

The transition from chariots to true cavalry was a gradual and uneven one. Occasional depictions of ridden horses have survived from early in the second millennium BC, but most seem to represent single messengers or scouts, ill-equipped for combat, or charioteers fleeing on team horses cut loose from wrecked chariots. Written references can be ambiguous as some of the terms equivalent to ‘horsemen’ may refer to chariot crews. It seems, however, that by the late second millennium BC units of cavalry may have been making their appearance on Middle Eastern battlegrounds. A twelfth century BC plaque from Ugarit in Syria may be the earliest depiction of an organized unit of horsemen, although only one is definitely armed.

The transition is easiest to follow in Assyria from the ninth century BC, due to the surviving record of relief carvings and inscriptions. Assyria had by then become the dominant power in the region, the Hittites and Egyptians having been severely weakened by migrations and invasions of the ‘Sea Peoples’. Over the next two centuries a succession of aggressive Assyrian kings carved out the largest empire yet seen, at its height incorporating all of Mesopotamia, Syria, Palestine and Egypt. Although the Assyrians are often credited with being the first to field an organized cavalry force, what can be seen in the surviving evidence may well be a response to developments in the regions beyond their expanding borders.

Urartu, modern Armenia, was a regular target of Assyrian campaigns in which many horses were taken in the form of booty or as tribute payments. Urartu was in direct contact with the steppe peoples to the north and it seems likely that this region was the conduit for the adoption of cavalry in the Middle East, as it had been for the initial introduction of the domesticated horse. An inscription of Menua of Urartu (810-785 BC) lists his forces for one expedition as 1600 chariot and 9174 cavalry. 20 Even if the numbers are inflated, the ratio of cavalry to chariots indicates that conversion was well advanced.

The development of Assyrian cavalry was heavily influenced by their charioteering experience and traditions. Bas-relief sculptures from the palace of Asurnasipal II show riders working in pairs, one armed with a bow and the other with a spear. Most strikingly, while the archer concentrates on shooting, his partner holds his reins for him, continuing the specialization of archer and driver. Both horses and riders are unarmoured. One of the key advantages of this type of unit over chariots was that they were better able to cope with rough terrain, an advantage that would have become immediately obvious in the rugged terrain of Armenia. At least as significantly, they were cheaper as the chariot, which required a lot of skilled labour, was not required.

Asurnasipal II’s riders still had a lot to learn from their neighbours, however, as they are shown sitting well towards the rump of the horse. This not only makes good balance and control difficult but risks bruising the horse’s vulnerable kidneys. The rearward seat had been used on donkeys and asses because it is the only position on them that is not akin to riding a bread knife, but trying to transfer the same method to horses must have retarded Assyrian riding prowess. It may cause wonder that correct riding techniques took so long to develop, but let us not forget they didn’t have approved riding schools and manuals to go by. It was only in the nineteenth century, after all, that Federico Caprilli (1868-1907) popularized the practice of leaning forward over jumps in western Europe, something now so widely accepted as the correct technique that it seems mere common sense.

By the reign of Tiglath Pileser III (745-27 BC), Assyrian reliefs show us horsemen armed only with long thrusting spears, maybe seven feet long, and swords. Some are armoured with helmets and sleeveless scale vests that come only to the hips, allowing the riders to bend freely at the waist. These may be the first confirmed heavy cavalry, for their one spear armament was obviously only of use in close combat, while their body armour was an unnecessary encumbrance and expense for mere scouts or messengers. Significantly, although they are still depicted in pairs, which may be merely artistic convention, they are all managing their own horses and sitting much further forward, just behind the horse’s withers.

Cavalry did not suddenly replace chariots in Assyrian armies; chariots were still used alongside them until Assyria’s destruction. The fact that chariots continued to be used may seem surprising to the modern mind used to thinking in terms of linear technological evolution, with each technology being rapidly replaced in turn by a superior one. It may be significant that these last Assyrian chariots were of the heavy, four-horsed type with four armoured crewmen, which may indicate that the shock role was the last to be taken over by cavalry. Here chariots may have retained some advantage due to their imposing bulk and noise, which would have increased their psychological impact on the target.

Probably more significant in the slow disappearance of chariots was the fact that they were symbols of prestige and had been the most obvious distinguishing feature of an elite for a thousand years. They were almost certainly at the centre of a web of tradition, custom and value that would not be quickly thrown away, even if they were being outperformed in a purely military sense. That the prestige value of chariots was greater than that of the ridden horse is demonstrated by the fact that they continued in use as transport for kings and generals long after all their other battlefield roles had been usurped by ridden horses. No doubt ancient grandees felt the chariot more befitting to their dignity, just as modern ones are more often seen in chauffeured limousines or staff cars than walking or bicycling.

When Sargon II launched a campaign against Urartu in 714 BC, the terrain was so rough that the chariots were the first sent home, while the king continued with the infantry and cavalry. The king’s chariot was retained, however, even though it had to be dismantled and carried in places. Eventually the weary Assyrians found Rusash’s Urartian army, also containing both cavalry and chariots, deployed for battle across their path, ready to fall upon them as they straggled along in column. Caught at a massive disadvantage and with no time to deploy, Sargon in his lone chariot seized the initiative and led the vanguard of cavalry in a pre-emptive attack.

The unhappy troops of Assur [Assyria] who had marched by a distant route, were moaning and exhausted … I did not look back, I did not use the greater part of my troops, I did not raise my eyes. With my chariot alone and with the cavalry who march at my side, who never leave my side in a hostile and unfriendly land … like a mighty javelin I fell upon Rusash

The Urartians broke and fled with heavy casualties inflicted upon infantry archers and spearmen as well as their cavalry: ‘his destruction I accomplished, I routed him… His warriors who bore the bow and the lance before his feet, the confidence of his army, I slaughtered. His cavalry in my hands I took and I broke his battle-line’. Rusash and the chariots meanwhile took refuge in their camp, but when Sargon brought up archers and javelinmen, the Urartian king abandoned his chariot and fled on horseback.

The account is from an inscribed tablet bearing a letter from Sargon II to the Assyrian god, Assur, presumably intended as an offering of thanks for the victory. While not as detailed as might be wished, it does at least demonstrate that one of the fundamental principles of the use of shock cavalry (which presumably applied also to heavy chariots) had been grasped by some. Because the physical and psychological impact of cavalry upon an enemy is multiplied by speed, and because horses make vulnerable targets when stationary, it was one of the fundamental principles of cavalry tactics up to the early twentieth century that cavalry should always attack rather than wait to receive an attack. The author of this advice from a typical nineteenth-century tactical manual would certainly have approved of Sargon.

Its action is confined to shock action. Hence it should always attack; at the moment of doing which it should attain its maximum speed. As it is powerless at the halt, it should, to defend itself, always advance to the attack.

Moreover, Sargon’s cavalry were not merely protecting themselves. By using their speed to fall upon the enemy before they had time to formulate a response, Sargon was able to wrest the initiative and save his army from disaster.