The false Congress of Prague afforded the new members of the Coalition time to rebuild their militaries to create a crushing superiority. The 300,000 men of the French army and its allies now faced 600,000 enemy combatants.

Their initial dispositions were in the form of a pincers, reflecting a strategy to encircle the Grand Armeé between Dresden and Leipzig. In the north, Bernadotte commanded a Swedish-Prussian army of 150,000 men. East of the Katzbach, a tributary of the Oder in Silesia, Blücher controlled 100,000 Russo-Prussians. To the south in Bohemia, Schwarzenberg commanded the most important army, composed of 200,000 Austrians and 50,000 Russians. A further 100,000 Russians were en route with Barclay de Tolly. Arguing that Austria had furnished the most important contingent, Metternich had imposed Schwarzenberg as commander-in-chief, or more correctly coordinator-general. To their pincers strategy, the Coalition members added a tactic that was flattering to the military renown of Napoleon: refuse battle wherever he was located, and act offensively only against his lieutenants.

Of course, Napoleon had profited equally from the suspension of arms to increase as much as possible the Grand Armeé effectives and artillery (1,200 cannon). He had paid special attention to the cavalry, increased to 40,000 but unfortunately without experience. At their head stood the best of them, Murat, who had repented and decided to rejoin Napoleon. But he no longer had the dash and enthusiasm of yesteryear. Moreover, Napoleon was aware that Murat had not completely severed his contacts with the Austrians.

At the renewal of hostilities, the French army was in a waiting posture between Leipzig and Dresden, holding off three enemy armies: in the north, Oudinot (70,000 men) opposite Bernadotte; in the east, Ney (100,000) opposite Blücher, including Marmont’s, Macdonald’s, and Lauriston’s corps; to the south, Gouvion Saint-Cyr (100,000), opposite Schwartzenberg. Napoleon remained in the center with the Guard (30,000 men).

Napoleon’s strategy was imposed on him by the disposition of forces on the terrain. Once again, he had to compensate for his overall numerical inferiority by a succession of local superiorities, accomplished by lightning concentrations, permitting him to defeat the enemy armies in detail. The disposition of opposing forces helped him in this task. His unsurpassed rapidity of execution and his legendary coup d’oeil would do the rest.

To this general concept of maneuver, Napoleon added a diversion toward Berlin by Davout’s corps, advancing from Hamburg in liaison with Oudinot’s offensive. This deception story was meant to distract Bernadotte, who constituted the northern arm of the enemy pincer.

To the diplomatic infamy of a false armistice, the Coalition now added military dishonor. On August 12, Blücher violated the ceasefire that had not yet expired. He surprised Ney’s units in bivouac on the Katbach, threatening to destroy them. Napoleon marched the Guard with all speed from Goerlitz to the Neisse River. As soon as he became aware of the emperor’s presence, however, Blücher withdrew.

The inspiration of this violation of the law of war was none other than Jomini. This former Swiss clerk who had become Ney’s chief of staff by his favor and that of Napoleon had recently passed to the enemy side. In so doing, he took a quantity of valuable intelligence concerning the French army. He succeeded in persuading the Coalition monarchs to initiate hostilities before the expiration of the armistice, so as to surprise the French in the midst of their preparations. The anticipated results were supposed to eclipse the dishonor of the proceeding. These noble monarchs did not hesitate to thus sacrifice their honor and violate their oaths! Later, this criminal would push into military literature, where he obtained more success than on the battlefield, without ever convincing the true specialists in the art of war. Determined in his desire to justify his treason, his account of the Napoleonic Wars failed to conceal his bitterness at not being rewarded for his alleged merits when he was still loyal to Napoleon.

In time, Napoleon was able to detect the trap that had been prepared for him. Blücher’s abortive attack was in reality only a lure to distract Napoleon’s army eastward while Schwarzenberg was to seize Dresden in his rear, cutting all his communications. The infamous violation of the armistice did not achieve its purpose because of Napoleon’s lightning return to Dresden, outrunning Schwarzenberg by covering 140 kilometers in three days.

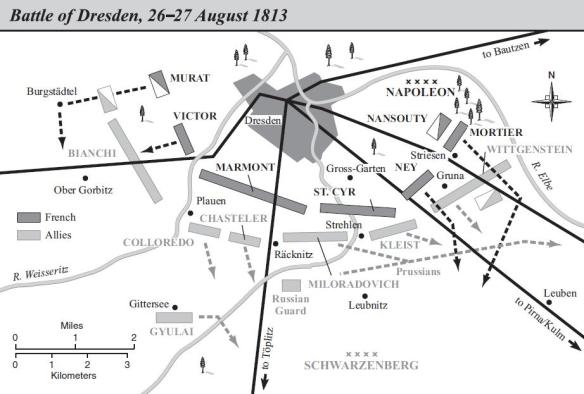

The Battle of Dresden took place on August 26-27, 1813. The first day, Napoleon contained the general Coalition assault to the west of the city. The next day, he counterattacked the Austrian left in force, overthrowing it. Then he exploited the resulting penetration in a southerly direction, threatening the rear of Schwarzenberg, who rightly ordered a general retreat on Bohemia in mid-afternoon.

Thus Napoleon seized his last great victory. The Coalition left on the field 15,000 killed or wounded, 25,000 prisoners, 40 cannon, and 30 regimental colors. The French army suffered 10,000 killed or wounded.

The fruits of this victory were lost, unfortunately. Given the dispersion of the Coalition partners, the resolute pursuit of the enemy to complete his defeat could only be conducted in a decentralized manner. Left to their own devices, in several days Napoleon’s lieutenants squandered the benefits of victory. To the east, Blücher severely thrashed Macdonald on the River Katzbach. In the south, Vandamme missed the opportunity for a great victory over Schwarzenberg at Kulm, and found himself a prisoner instead. To the north, Ney allowed Bernadotte to defeat him at Dennewitz.

A new and more serious period manifested itself. Allied troops began to desert en masse and turn against the French army. On August 23, 10,000 Bavarians and Saxons abandoned the ranks of Oudinot’s corps, defeated by Bernadotte at Grossbeeren. This was the first tangible sign of the surge of German nationalism in European affairs, a fatal blow to the Grand Armeé.

The appearance of national sentiment in Germany dated from the uprising in Spain. Elated ideologues were its champions, including Gentz, Schlegel, and Stein, excited by French turncoats at work in European courts. The dominant idea was to oppose the French democratic revolution with a stronger patriotic counter-revolution.

Having been hostile to this movement out of fear that it might turn against them, the German monarchs embraced it once they became aware of the enormous benefits they could draw from nationalism. Napoleon’s great power resided in his charismatic image as a liberator of peoples. If one could succeed in substituting an exalted nationalistic sentiment for menacing class consciousness, one could change radically the correlation of forces. What could be easier than to indirectly mobilize support to defend the monarchical classes by those who would otherwise threaten those classes? Deprived of his democratic striking force, Napoleon could not resist the rising patriotic tide. These sorcerer’s apprentices risked nothing in the short run. Unpolished and unorganized, in 1813 the popular masses could not suspect this diabolical twist of consciousness. Yet, in 1848, the monarchies belatedly realized that they had played with fire.

After several years of development, German nationalism erupted sharply and helped defeat Napoleon militarily. It was too late for him to regret his failure to arouse the conquered peoples against their oppressive sovereigns.

The first defections began to spread. The German alliances weakened and then reversed themselves in a fatal sequence. On October 8, Bavaria passed to the Coalition camp. This reversal gravely threatened the communications of the Grand Armeé.

The turmoil in Westphalia caused its king, Jerome, to quit the capital, Kassel, on September 30. At Bremen, a popular uprising forced its garrison to surrender to the Cossacks on October 15. Württemberg quit the French alliance on November 2. In short, the rats departed the sinking ship.

As an added burden, on November 8 Murat offered to ally himself with the Coalition, with Rome as the price of his treason.

In these dramatic circumstances, Napoleon had only one concern: to save his army, which was surrounded on all sides and threatened with destruction.

The balance of forces having become too unfavorable, for the first time Napoleon’s war aim was no longer the destruction of enemy armies, but the neutralization of them by a skillful blow, permitting him to withdraw behind the Rhine under the best conditions possible. This was the objective he chose after entrenching at Leipzig.