The Battle of Ain Jalut, 1260. (a) Phase I: Kit-Boga’s Mongol cavalry encounters Baybars’ advance guard of the Mamluk army near the village of Ain Jalut. The steppe horsemen launch a ferocious charge (1) and the Mamluks break and flee back up the Jordan River valley (2). Kit-Boga gives chase, falling for what is a normal Mongol ruse – drawing an enemy into a trap through feigned retreat. (b) Phase II: The fleeing Mamluk survivors draw nearer to their main force under Kotuz (1), but the sultan is wary of the Mongols and stands fast, even though he outnumbers the steppe warriors. Kit-Boga orders part of his force forward (2) to crush the enemy vanguard while another element sweeps right (3) to assault the Mamluks’ left flank. Baybars manages to gain the safety of the Mamluk main body (4), but the remainder of his force is destroyed. (c) Phase III: Kotuz pulls troops from his right flank (1) and rushes them across the field to buttress his assailed flank (2). For most of the morning, the Mamluks trade charge and countercharge with their Mongol opponents (3), slowly eroding the strength of Kit-Boga’s outnumbered force and regaining the left flank. (d) Phase IV: The Mamluks’ superior numbers enable them to work cavalry forces around the Mongol’s flanks and rear and trap the survivors (1). Kotuz rides out in front of his bodyguard and removes his helmet to identify himself to his troops as he leads a final charge (2). Kit-Boga orders his men to fight to the end but they are quickly overwhelmed, with few escaping to fight another day. From Warfare in the Medieval World by Brian Carey, Josh Allfree and John Cairns published by Pen & Sword

In the autumn of 1259 Hulagu crossed the Euphrates and pushed into Syria, then moved toward the crusader states in the Levant. Though a Buddhist, Hulagu was surrounded by Christians at his court. His senior wife was a Christian, and so was his favourite commander, Kit-Boga. Hulagu was pragmatic when it came to adding knowledgeable assets to his campaign, and the crusaders were well versed in warfare in the Levant. Many of the Latin crusaders in the northern principalities recognized that resistance to the Mongol horde was futile, and joined the steppe warriors in their war against Syrian Muslims, hoping that the alliance would return to Christian control their greatest prize, Jerusalem. When King Hayton I of Armenia rode south to join the khan, he was joined by his son-in-law Count Bohemond VI of Antioch and Tripoli. This would be the only western European army ever to march beside the Mongols, though other western commanders would seek Mongol support. Joined by these additional Christian crusaders, Hulagu besieged Aleppo, taking the city and massacring its inhabitants. The victory proved to be a mixed blessing. Hulagu rewarded Hayton and Bohemond with territories that had been won from them by the Muslims over the years, but the pope excommunicated the pair and their soldiers for fighting with the infidel.

By late March 1260, other terrified Muslim cities capitulated, including Damascus. Syria was now under Mongol rule and Hulagu took the title Ilkhan of Persia. Hulagu next looked toward the Mamluks in Egypt. But just as the death of Ogotai had saved western Europe from further Mongol incursions, news arrived from Karakorum that the great khan, Mangu, had died of dysentery, forcing Hulagu to return to Mongolia. The Ilkhan postponed the attack on Egypt and withdrew most of his army into Azerbaijan, leaving his general Kit-Boga and three tumans (30,000 men) behind to control the newly conquered territories in Syria.

In Cairo, Sultan Kotuz saw the departure of Hulagu’s main army as an opportunity to strike with a numerically superior force against the Mongol rearguard. Kotuz pulled together a large army of perhaps 120,000 men, including Mamluk soldiers from Egypt, and fugitives from failed Islamic campaigns (Bedouin tribesmen and Turcomans). Wanting to add to his numbers and secure his lines of communication, Kotuz sent a letter to the Latin crusaders, asking them to join him. The crusaders were torn by the offer. The grandmaster of the Teutonic Knights in Acre argued that an alliance with the Mongols was still the best policy, while others, fearing excommunication and military reprisals by their European comrades-in-arms, chose the middle ground, offering the Mamluk army safe passage and logistical support in their expedition into Syria.

The Mamluk vanguard left Cairo in late July under the command of Kotuz’s very capable general, Baybars. Like most of his Mamluk brothers, Baybars was born a Kipchack Turk on the steppes of southern Russia, where he was captured by the Mongols as a youth; he was then resold to an emir in Egypt (Mamluk is Arabic for ‘slave’). There, he was trained as a young man in the Egyptian tradition as a warrior slave, perfecting his skills as a rider, archer, lancer and swordsman. The Fatimid (909–1171) and Ayyubid (1171–1250) rulers of Egypt were the first to build armies of slave soldiers, and some, like Baybars, even rose to positions of power and influence, commanding the armies of caliphs and sultans. But in 1250 the Mamluk slaves usurped the power of their Ayyubid masters and founded a dynasty that would last over two and a half centuries.

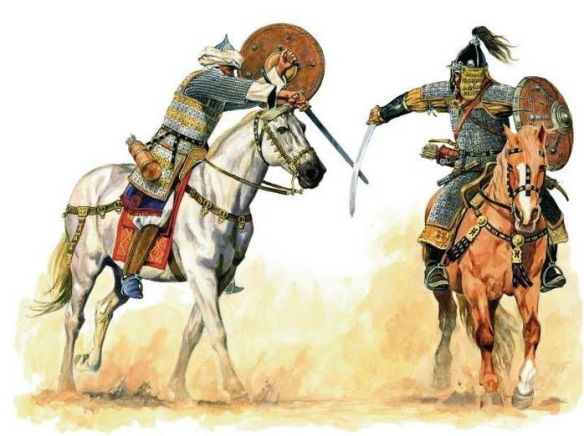

After years of arduous training, these young Mamluk warrior slaves would graduate and be freed, then be enrolled into their master’s household as his elite personal soldiers. One fourteenth-century Mamluk training manual, entitled Wish of the Warriors of the Faith, showed a blending of nomadic and civilized military practices, placing an emphasis on various tilting techniques and mounted archery, and illustrating the importance the Mamluks placed on both heavy and light cavalry. As elite soldiers, these Mamluks were dressed in mail or lamellar armour and wore conical iron helmets with mail coifs, protected very similarly to Persian, Greek and Byzantine cataphracts. Their shields were small and round, perfect for warriors who used both shock and missile combat from horseback. The Mamluks also utilized European-style straight and double-edged swords and maces, much like their crusader neighbours.

When news of the Mamluks’ approach reached Kit-Boga, he prepared to meet the Islamic army, but a rebellion in Damascus slowed his progress. Meanwhile, the Mamluks moved north and camped outside Acre, and, as promised, received crusader assistance. Mongol spies reported back to Kit-Boga on the size and complement of the Islamic army, and though he recognized that he was outnumbered nearly five to one, he left Damascus with an army of some 25,000 men, mostly Christians and made up of Mongols, Georgians and Armenians. On 3 September 1260 he crossed the Jordan River and rode along the plain of Esdraelon between the mountains of Gilboa and the hills of Galilee. Entering the valley where David slew Goliath near the village of Ain Jalut (‘Goliath’s Spring’), Kit-Boga’s Mongol army met the Mamluk vanguard under Baybars.

The Mongol cavalry charged the Mamluk van, which broke under the ferocity of the steppe warrior attack and fled up the valley. Kit-Boga gave chase, but the Mongols were falling for their own ruse. Baybars was playing the traditional steppe warrior game of luring an attacker with a retreat. By all accounts, his forces fought hard, though he still anticipated that his van would not be able to meet Kit-Boga’s charge. The Mongols pursued the broken vanguard to where Kotuz and a large force of Mamluks were arrayed across the valley ahead of them. But even with vastly superior numbers, Sultan Kotuz was too cautious to attack the Mongol flanks. Understanding his tactical situation, Kit-Boga committed himself to engaging the entire Mamluk host, pressing into the rear of the Mamluk van as it reached its lines, then ordering the remainder of his army to wheel right and run the Mamluk front rank toward Kotuz’s left wing. Baybars escaped, but his van was destroyed and the left wing crumbled under the Mongol sweep. For most of the morning, the sultan tried desperately to regain his left flank, pulling men across from the right wing and covering with shock and missile countercharges, whittling away at the Mongols.

Eventually, Kotuz was able to regain his flank, and with his more numerous cavalry now on either side of the Mongols, the moment was right for a final attack. Taking off his helmet so that his troops could recognize him, Kotuz rode out in front of his bodyguard and led the final cavalry charge. The Mongol army fought well, with Kit-Boga ordering his men to fight to the last man, but eventually it was overwhelmed by the Mamluks’ superior numbers. Mongol battlefield casualties were around 1,500 warriors, while the rest scattered in flight. Local peasants joined in the slaughter, burning the fugitives alive as they hid in fields. Those few who escaped travelled north and sought sanctuary with King Hayton in Armenia. Although Mamluk casualties went unrecorded, they were probably moderate. Kit-Boga’s head was immediately sent back to Cairo with the first news of the Mamluk victory. Kotuz entered Damascus in triumph.

The Mamluks won at Ain Jalut using a combination of superior numbers and ruse, finally destroying the myth of Mongol invincibility. The Mamluks’ Turkish origins gave them a familiarity with the tactics of their steppe warrior enemy, while training as Egyptian slave soldiers showed them the benefits of well-armoured heavy cavalry, a tactical system closely associated with civilizations in the Near East. When the two forces met at Ain Jalut, the Mongols faced an army that mirrored its own tactical capabilities, and unlike the Christian armies defeated in Russia and eastern Europe, the Mamluks possessed tactical symmetry. Ain Jalut also marked the ascent of the Mamluks as the next great regional Islamic power. Within a year, Baybars assassinated Kotuz, seizing the throne as sultan of Egypt and Syria. Taking advantage of discord among their enemies, Baybars’ descendants defeated and expelled the last of the crusaders in Acre in 1291, ending their 200-year occupation of the Levant.

Eventually, the Mongol rulers in the Middle East took on the attributes of the peoples they had conquered. Mongol elites converted to Islam, Persian influence became predominant at court, and cities began to be rebuilt. By the fourteenth century, the Mongol Empire all across Eurasia began to disintegrate. But the damage to the old Islamic centres was done. The Abbasid Caliphate had been extinguished and the new centre of Islamic civilization was now in Cairo. The Mamluk dynasty continued to flourish until defeat by Napoleon at the battle of the Pyramids in 1798. Having regained the throne after the French withdrawal, it was finally defeated by the Ottoman Turks in 1811.