The Air Force fighter most successful against the MiGs in aerial combat was the F-4. The radar-guided AIM-7 Sparrow accounted for more of the victories than any other weapon. Others included the F-102 Delta Dagger, used in the early years of the war as support for bomber missions, and the Vought F-8 Crusader, another supersonic fighter, which was capable of carrying four 20-millimeter guns in addition to missiles. F-8 pilots downed an alleged nineteen North Vietnamese MiGs, the second largest total after the F-4s.

F-4 Phantom

The top fighter aircraft used by U. S. forces during the Vietnam War. The F-4 was a twin-engine, supersonic aircraft made by the McConnell Douglas Corporation. It was equipped with four guided missiles whose type and range varied depending on the craft’s mission. It also carried extra fuel tanks that could be jettisoned for greater maneuverability. Flown by pilots from the air force, navy, and Marine Corps, the F-4 was most often used on bomber support missions, also known as MiG combat air patrol (MIGCAP). MiGs were the common fighters flown by North Vietnamese pilots. The majority of downed MiGs, an estimated total of 137, were downed by F-4s, and all American aces, or pilots who downed at least five MiGs, flew F-4s. In addition to MIGCAP missions, F-4s were used for reconnaissance patrols. The craft were flown by the air force from bases in both Vietnam and Thailand, by the navy from aircraft carriers offshore, and by the marines from their air bases at Chu Lai and Da Nang.

Vietnamese Air Force (North)

Part of an air defense system that included antiaircraft guns, missiles, and radars. Outnumbered and technologically outclassed, the North Vietnamese Air Force (NVAF) inflicted many losses and forced the United States to divert valuable assets from strike missions to support missions.

NVAF inventory rose from about 30 aircraft in 1965 to 75 in 1968. By 1972, the NVAF had 93 MiG-21s, 33 MiG-19s, and 120 MiG-17s. These MiGs were small, highly maneuverable, and armed with heavy cannons as well as (on MiG-21s) two to four Atoll heat-seeking missiles. Under rigid ground control, MiGs lurked in the path of U. S. strike missions. MiGs used hit-and-run tactics, such as diving from high altitude at supersonic speeds through U. S. formations to fire a missile before escaping. U. S. aircraft were often forced to jettison their bombs, after which they could rarely accelerate fast enough to engage the nimble MiGs.

The NVAF exploited the U. S. rules of engagement. Airbases and surface-to-air missile (SAM) sites were built near so-called sanctuary areas (Hanoi, Haiphong, the Chinese border) that could not be attacked. Washington gradually lifted this restriction (1965-1968), but MiGs could always escape into Chinese airspace. The rule that MiGs could not be attacked without visual identification negated U. S. longrange air-to-air missile advantages and allowed MiGs to hide in clouds. President Lyndon Johnson’s personal control of target selection caused U. S. forces to attack predictably and permitted the NVAF to concentrate defenses and establish ambushes. Finally, the United States could not attack the command-and-control system that was the key to the whole air defense network.

In air-to-air combat, the NVAF lost a total of 195 MiGs; the U. S. lost 77 aircraft. The NVAF was finally overwhelmed in 1972-bombers plastered NVAF airbases and U. S. fighters achieved a 5:1 kill ratio over the MiGs. However, the NVAF’s true effectiveness should not be gauged by air-to-air losses but instead by comparison of the total offensive and defensive systems. Guns, missiles, and MiGs imposed heavy costs: from 1965 to 1968, the United States lost 800 men and 990 aircraft and spent $10 for every $1 in damage inflicted on North Vietnam. Moreover, the NVAF forced the United States to accompany each strike aircraft with many support aircraft (escorts, jammers, SAM suppression, tankers, airborne early warning, reconnaissance, combat search and rescue). This raised the cost of each mission and reduced the number of aircraft available to strike North Vietnam. In short, the NVAF was another component of Hanoi’s successful overall strategy of attrition.

Operation BOLO

Event Date: January 2, 1967

A ruse designed by the U. S. Air Force to engage Vietnamese People’s Air Force (VPAF, North Vietnamese Air Force) MiG-21s on an equal footing. Because the Lyndon B. Johnson administration prohibited U. S. aircraft from bombing airfields in the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV, North Vietnam) until April 1967, the U. S. Air Force sought another method of reducing increasingly dangerous levels of MiG activity in North Vietnam. Consequently, in December 1966 Seventh Air Force Headquarters planned a trap for the MiGs by exploiting deception and the weaknesses of the North Vietnamese ground radar network.

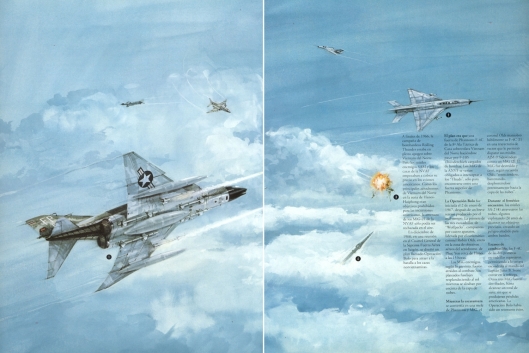

Normally U. S. Air Force strike packages flew in standard formations, which included refueling Republic F-105 Thunderchief fighter-bombers at lower altitudes than their McDonnell Douglas F-4 Phantom II escorts. In Operation BOLO, F-4s imitated F-105 formations-including their electronic countermeasure emissions, attack patterns, and communications-to convince North Vietnamese ground controllers that their radars showed a normal F-105 strike mission. However, when controllers vectored VPAF MiG interceptors against their enemies, the MiG-21s found F-4s, equipped for air-to-air combat, rather than the slower bomb-laden F-105s.

To maximize fighter coverage over Hanoi and deny North Vietnamese MiGs an exit route to airfields in China, Operation BOLO called for 14 flights of U. S. Air Force fighters to converge over the city. Aircraft from the 8th Tactical Fighter Wing (TFW) based at Ubon Air Base in Thailand would fly into the Hanoi area from Laos, while fighters from the 366th TFW based at Da Nang would arrive from the Gulf of Tonkin.

Marginal weather on January 2, 1967, delayed the start of the mission until the afternoon and prevented more than three flights of F-4s from reaching the target area. Colonel Robin Olds, 8th TFW commander, led the first of the three flights; Lieutenant Colonel Daniel “Chappie” James led the second flight; and Captain John Stone led the third flight. Olds’s flight passed over the Phuc Yen airfield twice before MiG-21s popped out of the clouds. The intense air battle that followed lasted less than 15 minutes but was the largest single aerial dogfight of the Vietnam War. Twelve F-4s destroyed seven VPAF MiG-21s and claimed two more probable kills. Colonel Olds shot down two aircraft himself. There were no U. S. Air Force losses. The VPAF admits that it lost five MiG-21s in this battle. One of the Vietnamese pilots shot down that day, Nguyen Van Coc, went on to become North Vietnam’s top-scoring ace, credited with shooting down nine American aircraft.

Ultimately Operation BOLO destroyed almost half of the VPAF inventory of MiG-21s. Although bad weather prevented the full execution of the plan, it did achieve its primary objective of reducing U. S. aerial losses. Because of the reduced number of MiG-21s, the VPAF had no choice but to stand down its MiG-21 operations.

References Bell, Kenneth H. 100 Missions North. Washington, DC: Brassey’s, 1993. Middleton Drew, ed. Air War-Vietnam. New York: Arno, 1978. Momyer, William W. Airpower in Three Wars: World War II, Korea and Vietnam. Washington, DC: U. S. Government Printing Office, 1978. Nordeen, Lon O. Air Warfare in the Missile Age. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1985. Pimlott, John. Vietnam: The Decisive Battles. New York: Macmillan, 1990. Ta Hong, Vu Ngoc, and Nguyen Quoc Dung. Lich Su Khong Quan Nhan Dan Viet Nam (1955-1977) [History of the People’s Air Force of Vietnam (1955-1977)]. Hanoi: People’s Army Publishing House, 1993.