To set the scene, in mid-1645 the Royalist troops had been badly mauled at the Battle of Naseby (14 June) and Langport (10 July). Charles maintained a stronghold in Wales and had retreated from most of England, but still hoped to link up with his allies in the north, bring in troops from Ireland and then perhaps drag victory from the jaws of defeat. Bristol had fallen (10 September) and so King Charles’s only port was Chester, then besieged by Parliamentary forces after much fighting for strategic control of Cheshire. Charles gathered what men he could and marched north along the Welsh border in the hope of relieving Chester and consolidating his forces with those of his supporters in Scotland, particularly Montrose. His course northward was paralleled by parliamentary forces under Sydenham Poyntz who had been instructed to prevent Charles from breaking out into the Midlands. At Chirk Castle, Charles, learning that Boughton had been overrun and that Chester itself (whose walls had been breached) might soon fall, hastened northward to the beleaguered city, arriving on 23 September 1645.

Military tactics in the civil war were based on cavalry, artillery and a combination of pikemen and musketeers (known as ‘pike and shot’). Before the bayonet had been invented pikemen and musketeers fought in mixed formations with the former protecting the latter. These were known as “Tercio” (later to evolve into the British infantry square as used at Waterloo). A cavalry charge at a facing block of pike was suicidal, so cavalry either discharged pistols when close to the pikemen, or tried to take them in the flank. Massed bodies of pikemen could not manoeuvre quickly (the 12-14 foot pike also slowed the rate at which armies could move), so cavalry could have the advantage on open ground. Artillery was mostly used for siege purposes and was improving to the point where the stone walls of castles and cities were being replaced by earthwork defences. In later years, improved firearms and the bayonet led to much more mobile infantry tactics.

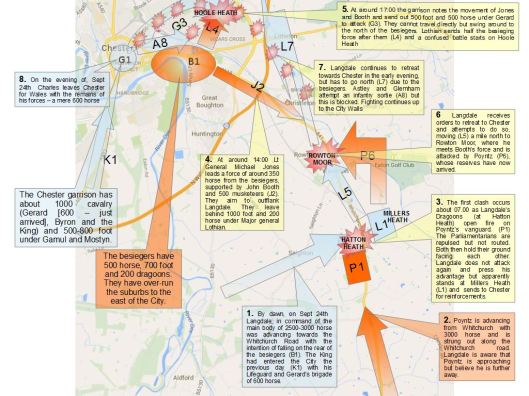

The events around Chester of 24 September 1645 were one of the last major battles of the first civil war and ended all hope of a Royalist victory.

As his fortunes waned in the west, England was largely lost to Charles. Naseby had been decisive for the Midlands and, therefore, the north. Royalist hopes flickered briefly in Wales, where Charles Gerrard fought a successful campaign against the parliamentary commander, Rowland Laugharne. In early July, Charles was in south Wales trying to raise troops to compensate for his losses in England, but there and in Hereford he was finding it difficult to press men. These hopes were extinguished by a parliamentary victory at Colby Moor (1 August), where successful co-ordination of operations on sea and land enabled Major-General Laugharne to rout the royalists under Sir Edward Stradling. It seemed that here too the royalist cause was crumbling, and Haverfordwest Castle fell on 5 August.

The King’s own army was now faced by both Fairfax and Leven, who had moved south during June, reassured that the King was not intending an invasion of Scotland. A week after Naseby he was at Mansfield and he was soon to lay siege to Hereford. Charles was finding it hard to get men, but he drew strength from news of Montrose’s continued successes. In May, Montrose had headed north from Blair Athol, away from the numerically superior Covenanting forces. In June fresh levies were made in the Highlands and by the end of the month he was sufficiently confident to offer battle to Baillie at Keith. This was declined but on 1 July battle was joined at Alford, where Montrose won another great, and bloody, victory. Charles now set his hopes on getting to Yorkshire, raising men there and, on the basis of garrisons at Pontefract and Scarborough, making some connection with Montrose. To join Montrose from the crumbling position in Wales was a tall order, however. Charles set off on a meandering and ultimately unsuccessful march, leaving Hereford only to return, via Doncaster, Huntingdon and Oxford, a month later. It was in Huntingdon that Charles heard of Montrose’s crushing victory over the Covenanters at Kilsyth. The most that could be said for his own march, however, was that Charles had avoided Leven’s army. The King entered Hereford on 4 September, having seen Leven’s siege of the city lifted, and spirits were a little higher.

Once in Hereford, however, Charles received flurries of bad news. Fairfax summoned Bristol to surrender on 4 September. Whereas the King had not been able to recruit in south Wales again in early September, Fairfax’s army was reinforced by 5,000 local people. Rupert recognized the desperate straits he was in and on 5 September asked for permission to communicate with the King. This was refused and he then spun out negotiations. On 10 September Fairfax lost patience and Bristol was stormed. Rupert surrendered and on the following day Bristol was evacuated. Charles blamed Rupert and, effectively, banished him.

Only Montrose’s campaign in Scotland offered the royalists any immediate comfort and, with his position in England deteriorating still further, Charles sought once again to join him. Marching from Hereford via Chirk he entered Chester with the intention of raising the siege. Langdale arrived to attack the besieging army from the rear, but was badly defeated at Rowton Heath. The parliamentary victory threatened the future of Chester, the only remaining port of importance for Ireland, and cut off the hope of a march northwards to Scotland through Lancashire. The final blow for this particular strategy was the catastrophic defeat of Montrose at Philiphaugh on 13 September. On 6 September, Leslie returned to Scotland with troops and three days later prominent supporters of Montrose among the Lowland aristocracy were imprisoned. Met in battle on 13 September, Montrose’s scanty cavalry were quickly disposed of and the foot destroyed. Two hundred and fifty Irish troops were killed and fifty or more surrendered on the promise of quarter. Most of them were subsequently shot on the pretence that the offer of quarter had applied only to officers, and a notorious massacre of Irish women and other camp followers then took place, which Leslie failed to stop. Charles had retreated to Denbigh, where, on 27 September, he heard the news from Philiphaugh and that Chester could not last much longer.

Charles had no remaining options. His field armies in Scotland and England were defeated and important garrisons were falling like dominoes. Cromwell marched triumphantly through the south, capturing Devizes (23 September) and Winchester (28 September), and arriving before Basing House a few days later. This was the seat of the Catholic Marquess of Winchester, and had successfully withstood two previous sieges, but it was to become the twentieth garrison to fall to the New Model Army since June. It had been under siege since August and Cromwell arrived on 8 October anxious to get the job done. Two great holes were blown in the walls by his heavy artillery, but still the defenders refused to surrender. As the infantry advanced in the ensuing storm they shouted, ‘Down with papists’, and many within were put to the sword despite pleas for mercy. Among the dead were six Catholic priests and a young woman who had tried to protect her father. Women were roughly handled, and partially stripped, although there were no rapes. The house was pillaged without restraint and the sudden release of food stores onto the local market temporarily depressed prices.

Basing held considerable symbolic significance; it had been besieged three times and was emblematic of loyalty and, to the King’s opponents, popery. The marquess, standing bareheaded in defeat among the ruins of his house, responded to taunts by saying, ‘If the King had no more ground in England than Basing I would venture as I did… Basing is called loyalty’. He added, perhaps pathetically or just unnecessarily, ‘I hope that the king may have a day again’. Among those humiliated by the conquerors was Inigo Jones, architect of the Banqueting House and designer of the court masques of the 1630s in which the majesty of the King had served to reconcile the competing passions of his people in order to bring peace.

Just as the war had started with a series of whimpers rather than a bang, so it petered out. Abandoning his northward march, Charles went initially to Newark, one of his remaining strongholds, where he was rejoined by Rupert, who was forgiven by a council of war on 26 October, and the King set out again for Oxford. In November 1645 Goring left for France, in part because of his health and partly in hope of a high command in the continental forces expected to be mustered the following spring. His command had passed to Lord Wentworth, who suffered heavy losses to Cromwell’s forces at Bovey Tracey on 9 January. Other garrisons surrendered in quick succession. Exeter was besieged and at Torrington, on 16/17 February, Hopton’s army was destroyed. The Prince of Wales fled to the Isles of Scilly, and Hopton to Cornwall, where he surrendered on 12 March. His army was disbanded over the coming weeks. Exeter fell a month later, leaving Pendennis Castle standing alone in the west, but even after the New Model Army had swept through the west the war twitched on. Hereford fell on 17 December and by then Chester and Newark were very strictly blocked up. Hopton’s had been the last force of any size in England, and Exeter the last significant stronghold aside from Oxford and Newark. Lord Astley had 3,000 men with him in Worcester and was ordered to try to cut his way through to Oxford, but the parliamentarians caught them at Stow-on-the-Wold, and Astley was forced to surrender on 20 March. In Wales, Raglan and Harlech held out, but without waiting for the fall of Oxford Charles could not really have been expected to delay surrender much longer than he did. He left Oxford in disguise on 27 April, surrendering to the Covenanters at Southwell on 5 May. As part of his surrender terms he delivered Newark on 8 May. When Oxford surrendered on 24 June, Prince Rupert and Prince Maurice left England for France and the Netherlands respectively. The last redoubts were Pendennis, which surrendered on 16 August, Raglan, which followed suit three days later, and Harlech, which held out until March 1647. It was a feeble end to the military campaign, but in surrendering to the Covenanters, Charles had shown some astuteness about the coming political campaign to win the peace.