During Mass one day in the winter of 1287–1288, King Edward I of England rose up from his throne to stand in honor of Rabban Bar Sawma, the newly arrived envoy from the Mongol Emperor Khubilai Khan. When he reached the court of the English king, Rabban Bar Sawma had probably traveled farther than any official envoy in history, covering some seven thousand miles on the circuitous land route from the Mongol capital, through the major cities of the Middle East, and on to the capitals of Europe. King Edward stood before the envoy not to offer submission to the Mongol Khan, but to accept bread from the hand of the Mongol envoy as part of the Christian sacrament of communion. Since the early European envoys to the Mongols had been priests, Khubilai Khan had chosen Rabban Bar Sawma because, although a loyal Mongol, he was also a Christian priest, albeit of the Assyrian rite.

Rabban Bar Sawma’s mission began as a pilgrimage from Khubilai Khan’s capital to Jerusalem, but after reaching Baghdad, his superiors diverted him to Europe in 1287. In addition to visiting with the Mongol Ilkhan in Persia, Emperor Andronicus II Palaeologus of Byzantium in Constantinople, the College of Cardinals in Rome, and King Philip IV of France in Paris, Rabban Bar Sawma made his way to the court of Edward, at the most distant point of his journey. He delivered letters and gifts to each monarch along his route, and he stayed in each court for a few weeks or months before moving on to the next. He used his time sightseeing and meeting with scholars, politicians, and church officials to tell them about the Great Khan of the Mongols, his subordinate the Ilkhan, and their burning desire for peaceful relations with the world. On his way back through Rome, Pope Nicholas IV invited Rabban Bar Sawma to celebrate Mass in his language; and then, on Palm Sunday, 1288, the pope celebrated Mass and personally gave communion to the Mongol envoy.

The crowned heads of Europe received Rabban Bar Sawma openly in their courts, but many prior envoys had been sent, only to be officially ignored by church and state. As early as 1247, during the reign of Guyuk Khan, Matthew Paris reported ambassadors from the Mongols arriving at the French court. Again in the summer of the following year, “two envoys came from the Tartars, sent to the lord pope by their prince.” During the earlier visits, however, European officials seemed afraid to let out any information about the Mongols. As Paris wrote, “the cause of their arrival was kept so secret from everyone at the curia that it was unknown to clerks, notaries and others, even those familiar with the pope.” Again in 1269, when the Polo brothers, Maffeo and Nicolo, returned from their first trip to Asia, they brought a request from Khubilai Khan to the pope to send the Mongols one hundred priests, that they might share their knowledge with the Mongol court.

With the tremendous emphasis on religious freedom throughout the Mongol Empire, Rabban Bar Sawma was surprised when he arrived in Europe and found that only a single religion was tolerated. He found particularly amazing that the religious leaders had so much political power over nations as well as more mundane powers over the everyday lives of the common people. As a Christian himself, he was delighted with the monopoly that his religion exercised, but it presented a stark contrast to the Mongol Empire where many religions flourished but had the obligation to serve the needs of the empire before their own.

Despite the publicity of his visit and the cordial reception across Europe, Rabban Bar Sawma fared no better in his mission than the other unacknowledged envoys; he failed to secure treaties with a single one of the European monarchs or church officials. His only success was that he managed to get a commitment from the pope to send teachers to the Mongol court as Khubilai had requested several times already. Failing in his diplomatic mission, Rabban Bar Sawma returned to the court of the Ilkhan in Persia, and related the events of his travels that were copied down in Syriac as The History of the Life and Travels of Rabban Swama, Envoy and Plenipotentiary of the Mongol Khans to the Kings of Europe. The trip of Rabban Bar Sawma, and particularly his serving communion to the king of England and personally receiving communion from the hands of the pope, illustrates how much the Mongols had changed the world in the fifty years since their army invaded Europe. Civilizations that had once been separate worlds unto themselves and largely unknown to one another, had become part of a single intercontinental system of communication, commerce, technology, and politics.

Instead of sending mounted warriors and fearsome siege engines, the Mongols now dispatched humble priests, scholars, and ambassadors. The time of Mongol conquests had ended, but the era of the Mongol Peace was only beginning. In recognition of the phenomenal changes of expanding peace and prosperity on the international scene, Western scholars later designated the fourteenth century as the Pax Mongolica or Pax Tatarica. The Mongol Khans now sought to bring about through peaceful commerce and diplomacy the commercial and diplomatic connections that they had not been able to create through force of arms. The Mongols continued, by a different means, to pursue their compulsive goal of uniting all people under the Eternal Blue Sky.

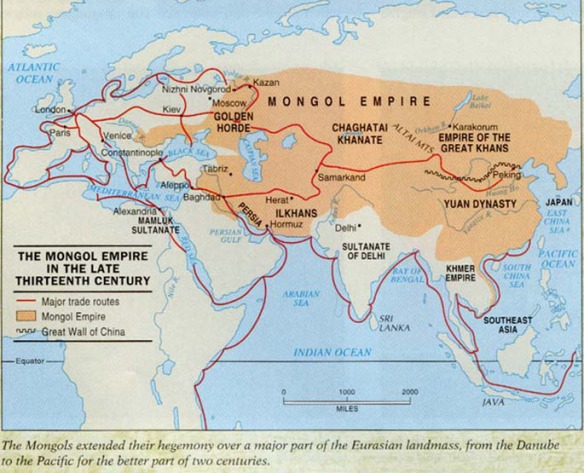

The commercial influence of the Mongols spread much farther than their army, and the transition from the Mongol Empire to the Mongol Corporation occurred during the reign of Khubilai Khan. Throughout the thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries, the Mongols maintained trade routes across the empire and stocked shelters with provisions interspersed every twenty to thirty miles. The stations provided transport animals as well as guides to lead the merchants through difficult terrain. Marco Polo, who was at the Mongol court at the same time that Bar Sawma was on his mission to Europe, frequently used the Mongol relay stations in his travels. With perhaps a little more enthusiasm than accuracy, he describes them as not merely “beautiful” and “palatial,” but also having “silk sheets and every other luxury suitable for a king.” To promote trade along these routes, Mongol authorities distributed an early type of combined passport and credit card. The Mongol paiza was a tablet of gold, silver, or wood larger than a man’s hand, and it would be worn on a chain around the neck or attached to the clothing. Depending on which metal was used and the symbols such as tigers or gyrfalcons, illiterate people could ascertain the importance of the traveler and thereby render the appropriate level of service. The paiza allowed the holder to travel throughout the empire and be assured of protection, accommodations, transportation, and exemption from local taxes or duties.

The expansion and maintenance of the trading routes did not derive from an ideological commitment of the Mongols to commerce and communication in general. Rather, it stemmed from the deeply rooted system of shares, or khubi, in the Mongol tribal organization that had been formalized by Genghis Khan. Just as each orphan and widow, as well as each soldier, was entitled to an appropriate measure of all the goods seized in war, each member of the Golden Family was entitled to a share of the wealth of each part of the empire. Instead of the salary paid to non-Mongol administrators, the higher-ranking Mongol officials received shares in goods, a large part of which they sold or traded on the market to get money or other commodities. As ruler of the Ilkhanate in Persia, Hulegu still had twenty-five thousand households of silk workers in China under his brother Khubilai. Hulegu also owned valleys in Tibet, and he had claim on a share of the furs and falcons of the northern steppes, and, of course, he had pastures, horses, and men assigned to him in the homeland of Mongolia itself. Each lineage in the Mongol ruling family demanded its appropriate share of astronomers, doctors, weavers, miners, and acrobats.

Khubilai owned farms in Persia and Iraq, as well as herds of camels, horses, sheep, and goats. An army of clerics traveled throughout the empire checking on the goods in one place and verifying accounts in another. The Mongols in Persia supplied their kinsmen in China with spices, steel, jewels, pearls, and textiles, while the Mongol court in China sent porcelains and medicines to Persia. In return for collecting and shipping the goods, the Mongols in China kept about three-quarters of this output for themselves; nevertheless, they exported a considerable amount to their relatives in other areas. Khubilai Khan imported Persian translators and doctors as well as some ten thousand Russian soldiers, who were used to colonize land north of the capital. The Russians stayed as permanent residents, and they remained in the official Chinese chronicles until last mentioned in 1339.

Despite political disagreement between contending branches of the family over the office of Great Khan, the economic and commercial system continued to operate with only brief pauses or detours because of sporadic fighting. Sometimes even in the midst of war, the fighting sides allowed the exchange of these shares. Khaidu, the grandson of Ogodei Khan and the ruler of the central steppe, was often in rebellion against his cousin Khubilai. Yet Khaidu also had extensive holdings of craftsmen and farmers around the Chinese city of Nanjing. In between sessions of fighting with Khubilai Khan, Khaidu would claim shipments of his Nanjing goods, and, presumably in exchange, he allowed Khubilai to collect his share of horses and other goods from the steppe tribes. The administrative division of the Mongol Empire into four major parts—China, Moghulistan, Persia, and Russia—did nothing to lessen the need for goods in the other regions. If anything, the political fragmentation increased the need to preserve the older system of shares. If one khan refused to furnish the shares to other members of the family, they would refuse to send him his share in their territories. Mutual financial interests trumped political squabbles.

The constant movement of shares gradually transformed the Mongol war routes into commercial arteries. Through the constantly expanding ortoo or yam, messages, people, and goods could be sent by horse or camel caravan from Mongolia to Vietnam or from Korea to Persia. As the movement of goods increased, Mongol authorities sought out faster or easier routes than the older traditional ones. Toward this end, Khubilai Khan launched a major expedition in 1281 to discover and map the source of the Yellow River, which the Mongols called the Black River. Scholars used the information to make a detailed map of the river. The expedition opened up a route from China into Tibet, and the Mongols used this as a means of including Tibet and the Himalayan area in the Mongol postal system. The new connections did more to connect Tibet—commercially, religiously, and politically—with the rest of China than anything else during the Mongol era.

During military campaigns, Mongol officials exerted a conscientious effort to locate and appropriate maps, atlases, and other geographic works found in enemy camps or cities. Under Khubilai’s rule, scholars synthesized Chinese, Arab, and Greek knowledge of geography to produce the most sophisticated cartography known. Under the influence of the Arab geographers brought in by Khubilai Khan, particularly Jamal al-Din, craftsmen constructed terrestrial globes for Khubilai in 1267, which depicted Europe and Africa as well as Asia and the adjacent Pacific islands.

Despite the initial reliance of commerce on routes created through military conquest, it soon became obvious that whereas armies moved quickest by horse across land, massive quantities of goods moved best by water. Mongols expanded and lengthened the Grand Canal that already connected the Yellow and Yangtze Rivers to transport grain and other agricultural products farther and more efficiently into the northern districts. Adapting Chinese engineering and technology to new environments, they built water projects throughout their territories. In Yunnan, the Mongol governor created a dozen dams and reservoirs with connecting canals that survived until modern times.

The failed invasions of Japan and Java taught the Mongols much about shipbuilding, and when their military efforts failed, they turned that knowledge to peaceful pursuits of commerce. Khubilai Khan made the strategic decision to transport food within his empire primarily by ship because he realized how much cheaper and more efficient water transportation, which was dependent on wind and current, was than the much slower land transport, which was dependent on the labor of humans and animals that required constant feeding. In the first years, the Mongols moved some 3,000 tons by ship, but by 1329 it had grown to 210,000 tons. Marco Polo, who sailed from China to Persia on his return home, described the Mongol ships as large four-masted junks with up to three hundred crewmen and as many as sixty cabins for merchants carrying various wares. According to Ibn Battuta, some of the ships even carried plants growing in wooden tubs in order to supply fresh food for the sailors. Khubilai Khan promoted the building of ever larger seagoing junks to carry heavy loads of cargo and ports to handle them. They improved the use of the compass in navigation and learned to produce more accurate nautical charts. The route from the port of Zaytun in southern China to Hormuz in the Persian Gulf became the main sea link between the Far East and the Middle East, and was used by both Marco Polo and Ibn Battuta, among others.

En route, the ships also called at the ports of Vietnam, Java, Ceylon, and India, and in each place the Mongol representatives encountered more goods, such as sugar, ivory, cinnamon, and cotton, that were not easily produced in their own lands. From the Persian Gulf, the ships continued outside of the areas under Mongol influence to include regular trade for a still greater variety of goods from Arabia, Egypt, and Somalia. Rulers and merchants in these other areas outside the Mongol system of influence did not operate within the system of shares in the Mongol goods; instead, the Mongol authorities created long-term trading relations with them. Under Mongol protection, their vassals proved as worthy competitors in commerce as the Mongols had been in conquest and they began to dominate trade on the Indian Ocean.

To expand the trade into new areas beyond Mongol political control, they encouraged some of their vassals, particularly the South Chinese, to emigrate and set up trading stations in foreign ports. Throughout the rule of the Mongol dynasty, thousands of Chinese left home and sailed off to settle along the coastal communities of Vietnam, Cambodia, the Malay Peninsula, Borneo, Java, and Sumatra. They worked mostly in shipping and trade and as merchants up and down the rivers leading to the ports, but they gradually expanded into other professions as well.

To reach the markets of Europe more directly, without the lengthy detour through the southern Muslim countries, the Mongols encouraged foreigners to create trading posts on the edges of the empire along the Black Sea. Although the Mongols had initially raided the trading posts, as early as 1226, during the reign of Genghis Khan, they allowed the Genoese to maintain a trading station at the port of Kaffa in the Crimea, and later added another at Tana. To protect these stations on land and sea, the Mongols hunted down pirates and robbers. In the Pratica della mercatura (Practice of Marketing), a commercial handbook published in 1340, the Florentine merchant Francesco Balducci Pegolotti stressed that the routes to Mongol Cathay were “perfectly safe, whether by day or by night.”

The opening of new trade routes, combined with the widespread destruction of manufacturing in Persia and Iraq by the Mongol invasions, created new opportunities for Chinese manufacturing. The Mongol conquest of China had been far less disruptive than the military campaigns in the Middle East, and Khubilai pressed for the expansion of traditional Chinese wares into these markets as well as the widespread transfer of Muslim and Indian technology to China. Through their shares, the members of the Mongol royal family controlled much of the production throughout Eurasia, but they depended on the merchant class to transport and sell these wares. Mongols had turned from warriors into shareholders, but they had no skill or apparent desire to become merchants themselves.

The Mongol elite’s intimate involvement with trade represented a marked break with tradition. From China to Europe, traditional aristocrats generally disdained commercial enterprise as undignified, dirty, and, often, immoral; it ranked with the manual trades beneath the interests of either the powerful or the pious. Furthermore, the economic ideal in feudal Europe of this time was not merely that each country should be self-sufficient, but that each manor estate should strive to be as self-supporting as practical. Any goods that left the estate should not be going to trade for other goods for the peasants on the land but to buy jewelry, religious relics, and other luxury goods for the aristocratic family or church. The feudal rulers sought to have their peasants supply all their own needs—to produce their food, grow their timber, make their tools, and weave their cloth—and to trade for as little as possible. In a feudal system, reliance on imported goods represented a failure at home.

The traditional Chinese kingdoms operated under centuries of constraints on commerce. The building of walls on their borders had been a way of limiting such trade and literally keeping the wealth of the nation intact and inside the walls. For such administrators, giving up trade goods was the same as paying tribute to their neighbors, and they sought to avoid it as much as they could. The Mongols directly attacked the Chinese cultural prejudice that ranked merchants as merely a step above robbers by officially elevating their status ahead of all religions and professions, second only to government officials. In a further degradation of Confucian scholars, the Mongols reduced them from the highest level of traditional Chinese society to the ninth level, just below prostitutes but above beggars.

Since the time of Genghis Khan, the Mongols realized that items that were commonplace and taken for granted in one place were exotic and potentially marketable in another. The latter decades of the thirteenth century became a time of nearly frenetic search for new commodities that could be marketed somewhere in the expanding network of Mongol commerce or for old commodities that could be marketed in a new way. It must have seemed that every item, from dyes, paper, and drugs to pistachios, firecrackers, and poison, had a potential buyer, and the Mongol officials seemed determined to find who and where that buyer might be. By responding to the needs of a universal market, the Mongol workshops in China eventually were producing not merely traditional Chinese crafts of porcelains and silks for the world market, but adding entirely new items for specialized markets, including the manufacture of images of the Madonna and the Christ Child carved in ivory and exported to Europe.

The Mongol promotion of trade introduced a variety of new fabrics by taking local products and finding an international market for them. The origins of such textiles can still be seen in the etymology of many of their names. A particularly smooth and glossy type of silk became known in the West as satin, taking its name from the Mongol port of Zaytun from which Marco Polo sailed on his return to Europe. A style of highly ornate cloth became known as damask silk, derived from the name of Damascus, the city through which most of the trade from the Ilkhanate of Persia passed en route to Europe. Marco Polo mentioned another type of fine, delicate cloth made in Mosul, and it became known as mouslin in Old French and then as muslin in English.

Even the most trivial items might yield a great profit, as when the new commerce sparked a rapid spread of card playing because merchants and soldiers found the light and easily transported game an entertaining and novel pastime. Compared to the more cumbersome objects needed for chess and other board games, any soldier or camel driver could carry a pack of cards in his gear. This new market stimulated the need to make card production faster and cheaper, and the solution for that process was found in printing them from carved blocks normally used for printing religious scripture. The market for printed cards proved much greater than that for scripture.