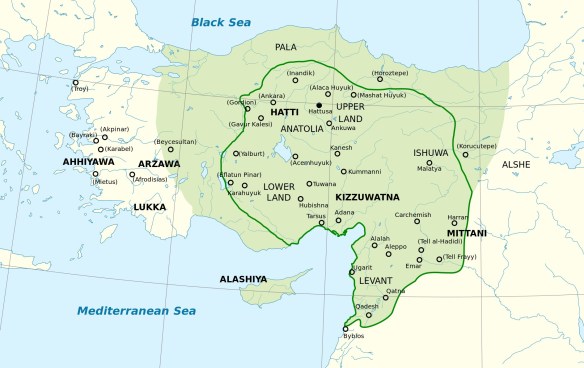

The Hittite Empire at its greatest extent under Suppiluliuma I (ca. 1350–1322 BC) and Mursili II (ca. 1321–1295 BC)

The approximate area of Hurrian settlement in the Middle Bronze Age is shown in purple.

PRINCIPAL COMBATANTS: Hittites vs. Hurrian Mitanni (later with Assyrian allies); separately, Egypt vs. Hurrian Mitanni

PRINCIPAL THEATER(S): Anatolia (Turkey) and the region of modern Palestine and modern Syria

MAJOR ISSUES AND OBJECTIVES: The Hittites and Hurrians struggled to dominate Anatolia.

OUTCOME: Dominance seesawed between the Hittites and Hurrian Mitanni but ultimately fell to Assyria, which became the dominant force in the region by the end of these wars.

The Hittite-Hurrian Wars are especially significant for having included the earliest battle of which a record- however incomplete-exists: the Battle of MEGIDDO, 1469 or 1479 B. C. E.

The Hurrians and Hittites vied for centuries to control Anatolia, the territory of modern Turkey. The long series of wars between them began about 1620 B. C. E. when the Hittites fought the Arzawa, a kingdom on their southwest border. Because the Hittites devoted most of their military resources to this struggle, they left south and southeast Anatolia undefended, and the Hurrian kingdom of Mitanni invaded and seized this region. In response, Hittite forces were rushed to the area and succeeded in ejecting the Hurrian Mitanni but, about 1600 B. C. E., were again involved in a pitched struggle for the city of Aleppo. After approximately five years of fighting, the Mitanni finally withdrew.

Some time after this victory, internal struggles within the Hittite kingdom weakened its military position, and the Hurrian Mitanni wrested Cilicia from the Hittites, establishing a kingdom called Kizzuwada about 1590 B. C. E. In a bold strategic move, the Mitanni also created the Hanigabat kingdom in the southeast, which effectively cut the Hittites off from northern Syria. This led to the Battle of Megiddo in 1469 or 1479 B. C. E., not between the Hurrian Mitanni and the Hittites, but between the forces of Egypt, under Pharaoh Thutmose III (fl. c. 1500-1447 B. C. E.), and Saustater (fl. 1500-1450 B. C. E.), the Mitanni king of the Syrian city of Kadesh. With the failure of the Hittites to contain Mitanni expansion, Thutmose feared losing influence in Syria and Palestine. He therefore led an army around the eastern end of the Mediterranean Sea to extinguish what he interpreted as a revolt in northern Palestine led by the king of Kadesh. The king’s rebel army marched south to Megiddo, which overlooked the pass leading to the Plain of Esdraelon and was thus a strategically placed high-ground position, the gateway to all Mesopotamia. Deploying his army in three groups, Thutmose made a surprise attack on the Mitanni position at dawn and routed the opposing force, which withdrew behind Megiddo’s walls. Had Thutmose proceeded against Megiddo immediately, the city would have quickly fallen. But his troops paused to loot the abandoned Mitanni camp, giving the defenders time to prepare strong defenses. As a result, Megiddo fell only after a seven month siege. The Battle of Megiddo must have involved very large forces, for it was probably the site of the Armageddon battle described in the New Testament.

The Egyptian victory at Megiddo stopped the Mitanni expansion. The Hittite “Old Kingdom” still languished in decline, however, until the advent of a new leader, Suppiluliumas (c. 1375-c. 1335 B. C. E.), who founded the “New Kingdom” and brought the Hittites to renewed power and influence. He resolved to end the Hurrian presence in Syria altogether by mounting a massive invasion into Syria. With strategic aplomb, he invaded via an unexpected route, through the eastern valley of the Euphrates, which caught the Mitanni entirely unawares. They offered only feeble resistance and, by about 1370, yielded all territory north of Damascus and all of present-day Lebanon.

Seeking to halt the Hittite advance, the Mitanni struck an alliance with Assyria, a rival of the Hittites, but the Hittites checked this move by conquering the Mitanni city of Carchemish on the Euphrates in about 1340. This gave the Hittites a buffer state between them and Assyria. It would be years before the Mitanni-Assyrian alliance retook the region in 1325. After the area around Carchemish had been retaken, the Hurrian Mitanni also reestablished Hanigabat as a subkingdom. By this time, however, both the Hurrians and the Hittites had greatly receded in importance relative to the Assyrians, who were rapidly becoming the dominant people in the region and were destined to possess all of Anatolia.

Further reading: Trevor Bryce, The Kingdom of the Hittites (New York: Oxford University Press, 1998); O. R. Gurney, The Hittites (New York: Penguin Books, 1990); J. G. Macqueen, The Hittites and Their Contemporaries in Asia Minor (London: Thames and Hudson, 1986).