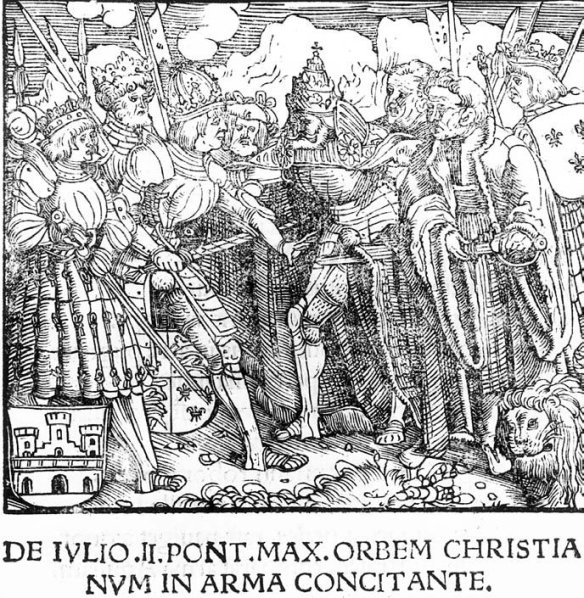

Pope Julius II in armour exhorting Emperor Maximilian, King Louis XII of France and King Ferdinand of Aragon to war on Venice

Raphael (attrib.), Julius II: this drawing is thought to be a contemporary copy of the portrait in the National Gallery, London, rather than a preliminary sketch.

In justice it must be noted that Julius himself declared at various points that his warmongering in Italy in defence of the rights of the Church was only the prelude to a great campaign against the infidel. It was reported, for instance, he had said that Agnadello was nothing to the victory he would win against the Turks. Cardinal Sigismondo Gonzaga reported in June 1509 that the Pope was commissioning many galleys at Civitavecchia, and that he himself had ordered six at Ancona which should be ready within a few weeks. He understood that Julius was determined to set forth in person; his plan was to give thanks to the Madonna of Loreto, then to tour the conquered lands in Romagna and make Bologna his base for organising the crusade; he hoped to celebrate Mass in Constantinople within a year. This objective was never entirely lost to sight. Even in his lowest hours in the Romagna in the spring of 1511, Julius allegedly asked the King of Scotland’s ambassador to persuade Louis XII to make peace and to launch a campaign against the infidel, in which the Pope would take part in person. It was in line with this papal resolve to settle the problems of Christendom expeditiously in order to face the long-standing external enemy that Cardinal Ximenes de Cisneros (1436–1517; a cardinal since May 1507, founder of the University of Alcalá and commissioner of the first polyglot Bible) vigorously led the troops – much to the annoyance of regular officers – at the siege of Oran in 1509, and declared that the smell of gunpowder was sweeter to him than all the perfumes of Arabia.

It should be clear that, even if Julius’s excesses of ferocious zeal and frequent lapses of self-control exposed him to serious criticism and mockery, he stood essentially within a long tradition, even a canonical tradition, that obliged the leaders of the Church to resort to arms – though preferably not to cause bloodshed by their own hands – when the Church was in danger. Even humanist writers endorsed this. In Julius II’s own time Paolo Cortesi, in his book De Cardinalatu (On the Cardinalate), had drawn upon the canon law tradition to itemise the occasions that should rightly drive a cardinal to war. In the course of discussing the moral qualities desirable in a cardinal, Cortesi listed under the heading ‘Fortitude’ nine such occasions when it might need to be applied, among them schism, heresy, sacrilege, attack on or nonrestitution of Church lands and cities, sedition, failure to pay taxes, etc. He gave as his example Julius II’s recent declaration of war against Venice, and the Romagna campaign in the spring of 1509 led by Cardinal Alidosi, even if fortitude was not a virtue very appropriate to Alidosi.

The portrayal of Julius in the famous anonymous dialogue Julius Exclusus is, of course, a gross if not wholly undeserved caricature. First printed in 1518, but previously circulating in manuscript, it was then and later usually attributed to Erasmus, in spite of his emphatic denials. Recently the English humanist Richard Pace has been nominated as the author, and Pace in his dialogue on education, De Fructu (1517), indeed claimed to have written an anti-Julius text some time between the death of Julius and election of his successor (February–March 1513); other parallels between the two dialogues, including a certain theatricality characteristic of Pace, have also been detected. Since Pace was Cardinal Christopher Bainbridge’s principal secretary and even had the skill – unusual then for an Englishman – of being able to write Italian as well as Latin, which he did on the cardinal’s behalf, and in an italic hand, the attribution is particularly interesting. For Bainbridge, like Julius, was also a bellicose character, and, although Pace may not have been with him in the military campaign against Ferrara in the spring of 1511, he must have appreciated that on this account Bainbridge was highly favoured by the Pope. Bainbridge was still alive in February 1513; Pace dedicated to him his translation of Plutarch’s Lives the following year, and mentioned him gratefully in De Fructu. So the purpose and motivation of Pace (if it was he) in risking his career by writing such a malicious diatribe against his patron’s patron remains obscure.

Various facets of Julius’s behaviour under the stress of war, as we have seen from Venetian and Bolognese sources, provoked surprise and shocked comment among contemporaries. But in general he was proceeding on traditional lines, though with rather stronger personal commitment and less restraint than his predecessors. Even the idea of taking nearly the whole papal court with him to the war zone or expected battlefield, as in 1506 and 1510–11, was not an innovation: had not Pius II tried to do just the same when he set off for Ancona in 1464? In December 1512 the preacher at the opening of the fourth session of the Lateran Council praised Julius to the skies for his conduct of ‘just war’ and his territorial gains for the Church. The neo-Latin poet Marco Girolamo Vida composed between 1511 and 1513 an epic ‘Juliad’ celebrating the Pope’s martial deeds, though unfortunately no trace of it survives (he went on to write his epic about the life of Christ). Fulsome praise for Julius’s bellicose character and achievements, was the summation of the distinguished Jesuit theologian and historian Cardinal Bellarmine (1542–1621) at the end of the sixteenth century. Bellarmine praised Julius for ‘recovering a great part of the ecclesiastical kingdom, which was done by diligence and virtue, imitating with great labour the virtue and diligence of famous and holy men, partly with his own armed forces, partly with the help of allies’.