circa.1724

Jacopo de’ Barbari, 1500

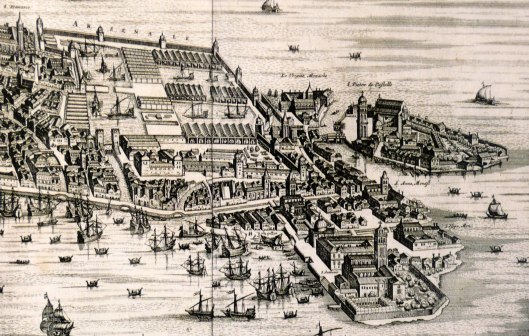

The physical demands of maintaining ships and supplying their crews tended to generate substantial supporting bureaucracies and physical infrastructure, making institutions like the Venetian Arsenal or the Tudor Council for Marine Causes more convincingly bureaucratic than those administering most contemporary armies, and naval bases like Le Havre, Portsmouth, and Finale nerve centres of royal authority. The comparatively high cost of ships, the need to victual crews for lengthy periods at sea, and the rising numbers of guns on ships made navies a weighty feature in state budgets and one that, unlike fortifications, was hard to cut back without serious long-term damage. By the later sixteenth century, the navies of maritime states like England and Spain cost more in peacetime than their standing armies and, even in wartime, when the number of troops employed on land rose dramatically, they might account for between 25 and 50 per cent of all military expenditure; Venice’s naval expenses in her wars against the Ottomans and Uskoks were similarly weighty. Ships were also tokens of royal magnificence for those who saw them and were named and decorated appropriately: Henry VII’s Sovereign, Henry VIII’s Henry Grâce à Dieu, Philip II’s Argo, painted with complex images and inscriptions linking Jason and the Argonauts to the Burgundian-Habsburg Golden Fleece, Magellan, and Columbus. Yet here too there are problems with a straightforward narrative of military expansion and state growth. Decentralised structures for naval administration, like those of the nascent Dutch republic, might prove more effective at harnessing expertise and channelling resources than more apparently modern institutions. Maritime communities, dependent on trade or fishing, might cooperate more productively with a ruler’s war aims under conditions of maritime truce, devolved convoying, or licensed privateering than in the construction of a state navy.

In response to rising sea power, mainly of the Ottoman Empire, Venice built up a reserve fleet rising from 50 galleys in the late fifteenth century to more than 100 after 1540. For the campaign of Lepanto in 1571 the Venetian arsenal turned out 100 galleys within two months, which represented about half of the Christian galley fleet.

Perhaps the most spectacular consequence of the slow and difficult but eventually successful adoption of broadside artillery on sailing ships was the return of the sailing vessel for warfare in the galley-dominated Mediterranean. Venice well represents this development. In 1499 the government-owned war fleet of Venice, which was maintained by the state in times of peace, had included a few very large sailing ships designed for war by shipwrights of the Venetian arsenal. But in the sixteenth century the building of such vessels had stopped; the arsenal then built only galleys. Next to its own galleys the Venetians also hired converted merchantmen. In 1618 they hired them for the first time from the Dutch and the English, who since the end of the sixteenth century had entered the Mediterranean for commercial ends. It soon became routine for both Venice and the Ottoman Empire to lease Dutch and English ships for their wars – a clear indication that these ships were now considered sufficiently effective for warfare next to galleys in the Mediterranean. In 1667 the Venetian arsenal built its first ship-of-the-line using an English warship as a model. During the next fifty years, sixty-eight ships-of-the-line issued from the arsenal. Even so, the republic’s Captain General of the Sea was still obliged to use a galley for his flagship as late as 1695, when the Turkish admiral used a ship-of-the-line.