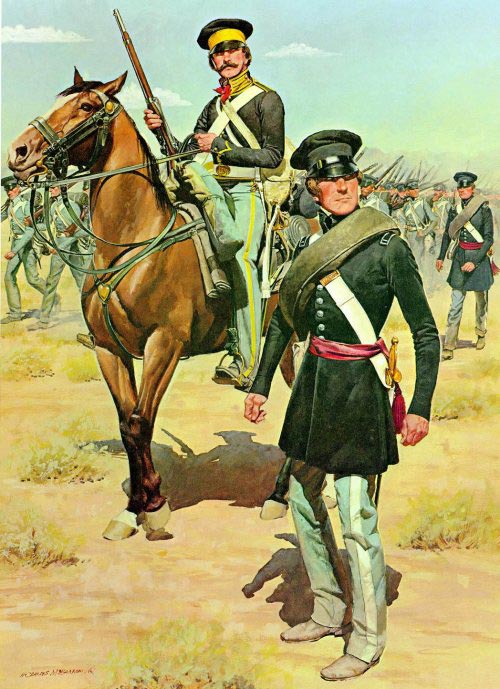

The 2nd Dragoons and the rest of the 1st Dragoons had joined General Zachary Taylor’s force which was attacking Mexico from across the Rio Grande. In May 1846, before the Rio Grande was reached, ‘Rough and Ready’ Taylor, as he was called, routed the Mexican cavalry at the Battle of Palo Alto with his infantry and artillery alone. Next day, however, while still short of the river, a splendid cavalry action took place. After sending his wounded to the coast, and leaving his wagon train under guard at Palo Alto, General Taylor moved forward with his army and came up with the Mexican force at Resaça. A deep ravine separated the two armies, but a road went round its eastern end. Behind the ravine and beside the road were placed the Mexican guns. When Mexican fire had halted the advance of the American infantry, General Taylor ordered Captain May to charge with his squadron of 2nd Dragoons round the east flank of the ravine against the guns guarding the road, while an American battery gave covering fire. This was just what Captain May liked doing, and he immediately thundered forward with his dragoons through the smoke, carrying the guns and scattering the Mexican infantry supporting them. And not only did he capture the guns. Rallying his scattered troopers under severe fire from Mexican infantry who had not been broken, he seized and carried off General la Vega himself. The American infantry then crossed the ravine and poured down the road at the double-quick, and the battle was won. Mexican losses at Resaça exceeded 1,000 even before the routed army reached the Rio Grande, where drowning raised the toll. The Americans had 33 dead and less than 100 wounded.

After the battle, Taylor continued towards the Rio Grande, and reaching Fort Brown prepared to cross the river. His crossing was completed by 20 May 1846, and he next moved against Monterrey, the capital of Northern Mexico. General Worth, who had been promoted after his successful campaign against the Seminoles in Florida, was in command of the force attacking Monterrey, and had to assist him in his task the famous Texas Rangers. Armed with rifles and Colts, mounted on wiry prairie mustangs, with outlandish dress and huge beards, and entering battle uttering horrible shrieks, they terrified the Mexicans. At Monterrey they acted as Worth’s shock troops. After making a wide encircling movement, they repelled a charge by Mexican lancers, and then dismounted and stormed the outer defences of the town. Finally, along with the rest of Worth’s force, they fought from house to house inside. This was the worst sort of dismounted fighting. The houses were built Mexican style, flush and almost blind to the street, with tough adobe walls and iron grilles on the few small windows. It took a full week to blast the defenders off the rooftops and out from behind the adobe walls and herd them in the centre plaza of Monterrey.

With a long line of supply and communication to hold behind him and no clear idea of just what he was expected to do in Mexico, Taylor was glad to get the city on any terms. He therefore signed an eight-week armistice with General Pedro de Ampudia and allowed the Mexican soldiers to march out of the town. It is hard to see how he could have taken them prisoner, since they outnumbered his entire force; but President Polk and the Commanding General of the Army, Winfield Scott, were outraged at what he had done. Taylor was ordered to redeem himself by marching at once on Mexico City. But he demurred strongly, and suggested instead that the assault should be made from the sea via Veracruz, by the route, in fact, that Cortes had used to capture the Aztec capital. To this Scott eventually agreed.

Meanwhile, the Mexicans counter-attacked Taylor’s forces which had reached Buenavista, south-west of Monterrey. Taylor had been reinforced, and among the troops which joined him from the north-west were two companies of the 1st Dragoons.

At Buenavista, Santa Ana attacked with 21,000 troops, against Taylor’s 4,500; and the battle that followed lasted two days and was the bloodiest of the war. In the first stage a large force of Mexican lancers and infantry advanced, and pushed back the American militia who were facing them, in spite of some spirited charges by the. Volunteer cavalry. The “routed militia fled through the local ranch and got crammed in the alleys between its buildings, where they were beset by the Mexican cavalry. This serious situation was resolved by the regular dragoons. Led by the redoubtable Captain May they thundered into the masses in the alleys, not caring greatly whether they struck friend or foe, and drove off the Mexicans. May’s charge proved to be the turning point of the battle. Immediately afterwards the whole American line began a general advance, which even the routed militia were prevailed upon to turn and join, and Santa Ana’s army was defeated. May, already brevetted twice for stirring charges, was again uplifted – now becoming ‘Colonel’ to his friends although still receiving a captain’s pay!

Some of Taylor’s troops were now sent to reinforce General Winfield Scott’s column advancing on Mexico City from Veracruz, and Taylor was ordered to hold on to the positions he had gained.

Scott’s cavalry was at first limited to three companies of 1st Dragoons, six of 2nd Dragoons and the newly raised regiment of Mounted Riflemen; the latter, however, having unfortunately lost most of their horses on the sea voyage, had thus to serve on foot – a great humiliation for a cavalryman! The wealthy Phil Kearny – nephew of Colonel Stephen Watts Kearny who led the dragoons to California – had mounted, at his own expense, his company of 1st Dragoons on splendid greys. These fortunately survived the voyage.

After Veracruz had been taken by storm, the American forces marching inland were forced to fight a series of actions against Mexicans in defence positions on mountain barriers across the National Road. At one of these, the Cerro Gordo, General Scott carried out a model operation to clear the way. First, Captain Robert E. Lee2 scouted round the Mexican flank and discovered a route to turn their position. Then, a flanking column swung round by it and cut the National Road while a frontal attack was keeping the Mexican defenders occupied. The Mounted Rifles played an important part in this battle, and not without loss, for they suffered 84 casualties.

After the battle enough horses were captured to mount two companies of Rifles, but the mounted men found that their infantry rifles were clumsy to use on horseback. After firing one shot they chose to charge the enemy rather than try to reload while mounted, which they could have done with a short cavalry carbine.

General Winfield Scott reached the outskirts of Mexico City in August 1847, and there defeated the Mexicans in two battles on successive days. In the second battle more horses were captured and more Rifles were able to revert to cavalry, this time some even doing so while the fighting was in progress. At one stage, Captain Phil Kearny at the head of his greys charged right through the enemy lines with twelve of his troops and captured a battery of enemy guns. Dismounted and isolated, they were so far ahead of their fellows that it seemed they must be lost; but the Mexicans proved too confused and bewildered to take advantage of the situation, and, quickly remounting, Kearny led his dragoons back through the Mexican ranks to safety, though one of his arms was shattered by a stray shot as he did so. This brave feat did not pass unnoticed by the Commander-in-Chief, for General Winfield Scott said later that he considered Kearny the bravest man he knew.

During the storming of Chapultepec castle, just before the entry of Mexico City, the Rifles charged the heights on foot, and next day received a striking acknowledgement by Scott, for it was their flag which was raised over the National Palace on its occupation. Also, when General Scott, escorted by Kearny’s dragoons on their grey horses, passed along the ranks of the Mounted Rifles drawn up as guards along his path, he exclaimed: ‘Brave Rifles! Veterans! You have been baptised in fire and blood and have come out steel.’ These words were later taken by the Mounted Rifles, who became the 3rd U.S. Cavalry in July 1861, as their regimental motto.

With the capture of Mexico City the war came to an end. The Americans occupied the place for nearly nine months until the end of May 1848 when a treaty of peace was finally ratified.