The muscle cuirass continued to be used as the most elaborate piece of body armour available to wealthier officers. It was presumably this type of cuirass that Epaminondas was wearing when he was injured ‘through the breastplate’ at Mantinea in 362 (Diodorus XV, 87.1). On the Nereid monument from Lycia, which dates to about 400 and is now in the British Museum, over 80 per cent of the soldiers are wearing simple material corslets, with only officers in muscle cuirasses. These cuirasses have the abdominal dip of the earlier cuirasses and are now depicted with anatomically correct pectoral muscles, rather than the spiral designs seen in the previous century. These Lycian models also appear without pteruges or shoulder flaps and must have had a fitted padded lining.

In the later fourth century there was an increase in the depiction of the muscle cuirass on the funerary monuments of Athens, which is thought to have been caused by the muscle cuirass having been reintroduced after a period when not much armour was worn. Sekunda suggested this might have been as a result of the defeat of Chaeronea in 338, when Athens and Thebes and their allies lost to the Macedonians, who were using the new sarissa-armed phalanx and heavy cavalry. However, several of the monuments can now be dated to before this. Sekunda (2000, p. 62 and plate J) still sees this as a general rearmament, and suggests that whole armies of Athenian hoplites and indeed Macedonian pikemen were equipped with the muscle cuirass. I think this is highly unlikely. We have seen that this form of cuirass was an expensive item and that at this time arms and armour were provided by the state. I do not see how either Athens or indeed Philip II of Macedon could have afforded large numbers of this form of cuirass for the ordinary soldier. This state funding, for Athens, probably began after Chaeronea and we know it consisted of just a shield, cloak and spear (Sekunda 1986, p. 57). The few stelai we have that feature this cuirass can easily be accounted for by officers, who could personally afford the cuirass (and indeed the grave stele).

These mid- to late-fourth-century cuirasses had separate shoulder pieces giving a double thickness of bronze (or iron) at this point, which now became a standard feature of the muscle cuirass. They were obviously copied from linen and leather shoulder-piece corslets. An example of a bronze-plated iron cuirass of this type was found in Tomb II at Amathus in Cyprus, but may be of Roman date (Gjerstad et al. 1935, vol. II, p. 14, no. 77). The British Museum has a pair of bronze shoulder guards, from Siris in Italy, which are very elaborately decorated. They are probably from the fourth century and so Greek rather than Roman. The only complete surviving muscle cuirass of this type from this period was found in 1978 at Prodromi, near Thesprotia in southern Epirus. The two iron helmets found in this tomb have already been mentioned, and the cuirass is also of iron, dating from about 330. The contemporary iron cuirass from the tomb of Philip II, which is discussed below, is made up of fairly manageable flat plates except at the shoulders, and it is this Prodromi cuirass which shows the real skill in iron working that the Greeks were now attaining. Iron is much harder to work than bronze, but it is a much stronger defence. The drawback is that it is also much heavier, especially because it was hard to work into thin sheets. No width measurements are given for the Prodromi cuirass in its original publication (Choremis 1980, pp. 10–12), but the cuirass of Philip II is 5mm thick compared to the usual 1–2mm for bronze cuirasses.

The Prodromi cuirass clearly reached down at the front to protect the belly, although some of it has broken away here. The edges at the neck and armholes are rolled over for added strength and the cuirass is hinged on the right side and at the shoulders. Straps passing through gold loops fastened the left side. The nipples are marked out in gold and next to these are gold rosettes with loops. Gold lion heads and loops on the shoulder flaps show that this is where the shoulder flaps were fastened down; the lion heads are identical to those on Philip II’s cuirass. The cuirass is very wide in the hips to allow the wearer to ride a horse, and the length of his machaira, 78cm, shows that this man was a cavalry officer. Another proof for this was the absence of greaves from the tomb, although they were not always a prerequisite for infantry at this time, as we have seen. It is an unusual, isolated tomb and Choremis, the excavator, has suggested it was possibly a battlefield burial.

Nothing remained of the pteruges in the Prodromi tomb, and we must return to the Athenian funerary monuments such as the tomb of Aristonautes (Snodgrass 1967, plate 56) and another well-known example from Eleusis (Sekunda 2000, p. 62). Both these monuments show three sets of pteruges protruding from the bottom of the cuirass, rather than the two sets that are more usual in fifth-century depictions. These fourth-century pteruges are also much shorter than earlier ones, barely covering the groin, let alone the thighs. Later illustrations, such as those on the Alexander Sarcophagus and the Alexander mosaic, show two sets of pteruges, one short and one long, frequently with pteruges at the armholes as well. These are material corslets, probably made in one piece, although they are perhaps evidence for a separate arming tunic that could be worn under a cuirass, like Xenophon’s spolas. Russell Robinson (1975, p. 148) illustrates a similar doublet, with one set of short and one set of long pteruges. As he explains, the upper short set of pteruges would have had to be carefully cut if they were to follow the curving, lower abdominal dip of a muscle cuirass, and this might have been a later Roman development. The fourth-century Athenian representations have no pteruges at the armholes, which seems to suggest that the three short rows of pteruges were attached directly to the cuirass or, to be more exact, to its lining. In this case one might have thought that two rows would have been sufficient, one covering the gaps in the other. The lower two rows seem to conform to this pattern but the upper row is generally much shorter, and I would suggest that only this row was attached to the cuirass. The lower two rows are more likely to have been part of an arming tunic, to help cushion the weight of the cuirass, rather than having the cuirass itself padded. Evidence for this (apart from Xenophon and his spolas) comes from the Amphipolis inscription dating from the time of Philip V, c. 200. This has a list of fines for soldiers and officers who needed replacement equipment, which is further evidence for the supply of equipment by the state. Here, ordinary soldiers were issued with a kotthubos for body armour, while officers received a cuirass or ‘half-cuirass’ as well as a kotthubos, suggesting that the two could be worn together. This suggests that the kotthubos was some sort of leather armour like the spolas, over which a metal cuirass could be worn.

There is little pictorial evidence for the use of the muscle cuirass under Philip II and Alexander. One is being worn by a warrior on the Alexander Sarcophagus, but Sekunda (1984, p. 33 and plate H) has shown that he is an allied Greek, not a Macedonian. It is an interesting example, since it has no pteruges and no shoulder guards and so is somewhat old-fashioned. Maybe the sculptor was using an old prop. It seems likely, however, that some of Philip II and Alexander’s soldiers did wear the muscle cuirass, especially the Companion cavalry. The muscle cuirass persisted in art through the third and second centuries and it is clear that wealthier Greeks and Macedonians continued to wear it. The victory frieze at Pergamum, which is now generally dated to c. 170 and celebrates the victory of Eumenes and the Romans over Antiochus III at Magnesia in 190, illustrates captured Seleucid and Galatian armour, and the scenes include three muscle cuirasses. Two are similar to the Prodromi cuirass apart from the shoulders. Instead of being tied down to the chest, the shoulder flaps have a central hole which passes over a stud or loop on the chest through which a securing thong is tied (Jaeckel 1965, pp. 103–4). Both cuirasses have two rows of pteruges at the waist, but only one has shoulder flaps. These are bordered and tasselled, and seem to be made of leather covered with fabric. The third muscle cuirass is shown without pteruges, which may be further evidence for their having been attached to a separate jerkin at this time: or perhaps we are again dealing with an old-fashioned cuirass, since it has no shoulder flaps. A Macedonian officer on the Aemilius Paullus monument also wears a muscle cuirass (Kahler 1965, plate 12), and there are at least four shown on the Artemision at Magnesia. This dates from after 150, and is a little confusing in that all the soldiers, not just those in muscle cuirasses, seem to be wearing officers’ sashes around the waist. Although these soldiers are shown on foot, one at least is clearly wearing boots and may therefore be a cavalry officer (Yaylali 1976, p. 106 and fig. 26.1).

These muscle cuirasses all have clean, unadorned lines (apart from the Siris shoulder flaps), but later Roman muscle cuirasses are often highly embossed. Indeed, some of the relief work is so high that it seems to consist of separate pieces of bronze sculpture, soldered onto the body and shoulder flaps of the cuirass (Russell Robinson 1975, pp. 149–52). This work was probably still further enhanced by painting. The Siris bronzes and a cuirassed statue from Pergamum (Journal of Hellenic Studies, 1985, pp. 77–8) suggest that these elaborate embossings may have begun in the Hellenistic period, but most of our evidence is Roman.

THE CUIRASS OF PHILIP II

The cuirass from the royal tomb at Vergina, which is almost certainly that of Philip II, merits a section on its own, because it is an iron cuirass but in the shape of a material shoulder-piece corslet. It has not been fully published yet, but has been well illustrated in several books (Andronikos 1977, pp. 26–7; Hatzopoulos and Loukopoulos 1980, p. 225, plate 127; Vokotopoulou 1995, pp. 156–7; Connolly 1998, p. 58). It is made of plates of iron, four forming the body, and two hinged, curved plates coming over the shoulders from the backplate, which itself curves outwards to allow space for the broadening upper back. The iron is 5mm thick, a good deal thicker than was usual for bronze cuirasses, and would have given a good deal of protection, perhaps even being catapult-proof (Plutarch, Life of Demetrius 21). The cuirass is decorated with gold bands around the borders of each piece, and a wide gold band around the body of the cuirass. Decorative gold panels are attached to each side, and there are six gold lion heads on the front of the cuirass. The middle pair and the top two, which are on the shoulder guards, hold gold rings in their mouths, through which straps fastened down the shoulder flaps. The pteruges no longer survive, but they were covered with gold strips which do, showing that there were originally fifty-six of them in two rows. Remains of cloth were found on the inside of the cuirass, which came from the padding or an arming jack, but more interesting was the fact that remains of material were found on the outside of the cuirass, adhering to the iron. It is clear that the outside of the iron was covered with decorative cloth, making it difficult to distinguish this cuirass from the linen and leather corslets also in use at this time.

This suddenly opens up the possibilities mentioned in the last chapter: that artistic depictions of shoulder-piece corslets may show iron or bronze cuirasses covered with cloth, rather than the material corslets most people accept them for. Sekunda advanced this thesis in Greek Hoplite (2000), but there really is no evidence in the form of other surviving metal plates. I think, given the evidence of the Philip II cuirass, that we must accept that such cuirasses may have existed in the Hellenistic period – unless the Philip II cuirass really is a ‘one-off’; but I don’t think we can backdate the idea to the fifth century.

HELLENISTIC MATERIAL CORSLETS

Information regarding material corslets comes mainly from sculptures, in which cuirasses of a shoulder-piece variety are often shown being worn. These were always generally assumed to be linen, or more likely leather, just like those of the fifth century, but the cuirass of Philip II shows us that some examples may be metal.

For the end of the fourth century the main source is the Alexander Sarcophagus, which shows several infantry soldiers and one cavalryman. The flexible positions of the infantry show that the shoulder-piece corslets they are wearing are surely leather. These corslets have two sets of pteruges, one perhaps attached to the corslet, the other a separate skirt, and were originally coloured purple and gold – although to what extent these reflect actual uniforms is uncertain (Sekunda 1984, plates E, F, G). In contrast, the cuirass of the cavalryman is plain white so may be linen, but could also be a material-covered metal cuirass (Schefold 1968, plate 51). Before the Battle of Chaeronea Philip II equipped both infantry and cavalry with cuirasses, but of what sort is unknown. The cavalry were the main strike force of the army and were more likely to be issued with metal cuirasses, especially as they would be less of an encumbrance for horsemen. When Alexander the Great and his army reached India, the phalanx corslets had worn out and 25,000 new sets were issued. The old corslets were burned (Sekunda 1984, p. 27). All these facts – that the corslets had worn out, that Alexander could get hold of 25,000 replacement sets almost immediately, and that the old sets were burnt – strongly suggest that the original infantry corslets were leather ones.

Further evidence for the use of material-and-metal corslets and metal cuirasses comes from an inscription from Amphipolis dating from the period of Philip V at the end of the third century (Feyel 1935, passim). This inscription concerns military regulations for the Macedonian garrison at Amphipolis and includes a list of fines for lost equipment. Soldiers were fined three obols for the loss of a sarissa or sword, one drachma for the loss of a shield, and two obols for the loss of greaves, a helmet or a kotthubos. Officers were fined double the amount for these items, either because they were supposed to be more careful or because their equipment was of better quality. Also, officers were fined one drachma for a half-cuirass and two drachmas for a cuirass.

This leads one to the assumption that only officers wore cuirasses; but what then are ordinary soldiers wearing when they are pictured in shoulder-piece corslets on various monuments? We must assume that it is the kotthubos. This word was interpreted by Feyel as being a set of pteruges, and it is true that the officers had them in addition to the cuirass (or half-cuirass), but the word equates with kossimbos, a shepherd’s leather coat, and could have meant a leather shoulder-piece corslet and pteruges. This could still have been worn by officers, as well as the cuirass, since it would have acted as an arming jack, and it equates much better with the sculptural representations that we have.

The cuirass mentioned in the Amphipolis inscription is generally assumed to be the muscle cuirass, with the half-cuirass being perhaps a breastplate only, which is certainly feasible. The number of officers to be so equipped is unclear but, if we count officers as file leaders and above, then we are looking at about 1,000 cuirasses and half-cuirasses for a phalanx of 16,000 such as Philip V had at the Battle of Cynoscephelae. I still think 1,000 is too great a number of muscle cuirasses to be state supplied and that we must be looking at a simpler type of cuirass. The alternative, of course, is provided by the cuirass of Philip II. A cuirass like that, made up of simple plates covered with material, could be supplied by the state in quantity. The designations of cuirass and half-cuirass may refer to the amount of each cuirass reinforced with metal. The cuirass worn by Alexander on the Alexander mosaic appears to show an iron plate on the upper part of the body, with the lower part protected by scales. Varieties such as these could easily have been known as half-cuirasses. The Artemision at Magnesia shows men in what are clearly material cuirasses, and some officers in muscle cuirasses; but it also shows some officers (with officer’s sashes) who wear shoulder-piece cuirasses, which are clearly made of metal. They have large armholes and the figures are shown in stiffer positions. Similarly, several of the shoulder-piece corslets on the Pergamum friezes could be metal-plated cuirasses. These are all depicted with officer’s sashes attached. Such adjustable corslets remind us of the fifth-century composite corslets, with their mixture of material and metal defences. Removing all the detailed work of the muscle cuirass meant that simple metal cuirasses, covered with material, could be afforded by many more soldiers – although I am personally tempted to connect such a corslet to the ‘half-cuirass’ of the Amphipolis inscription, and see its use restricted to cavalry and officers. I am sure that phalanx troops, and perhaps the hypaspists, only wore the leather shoulder-piece corslet for body armour.

GREAVES

The popularity of greaves continued to decline under Philip II and Alexander, when the introduction of state-supplied equipment seems to have taken its toll on this optional item. The tomb of Philip II contained three pairs of bronze greaves, and a further pair of gilded bronze greaves was placed in the antechamber; but the Athenian funerary stelai of the same period, which show muscle cuirasses, show no greaves. Two of the soldiers on the Alexander Sarcophagus are wearing greaves and both originally had feathers in their helmets, indicating that they were officers. Sekunda (1984, pp. 38–9) suggests that the soldier in bronze greaves is a half-file leader, whereas the other, who wears silvered greaves (possibly iron), is of a higher rank. These greaves, like those from Philip II’s tomb, show little anatomical detailing and are purely functional. Those on the Alexander Sarcophagus have a red lining and a red strap going right around the greave just below the knee, to help secure the greave to the leg. This evidence seems to suggest that only officers wore greaves; but the Amphipolis inscription of the late third century mentions fines for soldiers for lost greaves, showing that the phalanx of Philip V was equipped with greaves, though not necessarily in its entirety. A collection of lead tokens from Athens, which seem to be concerned with the state supply of equipment, suggest that Athens also supplied greaves to her heavy infantry (Kroll 1977, passim). The soldiers shown on the tomb of Antiochus II (third century) are not wearing greaves, and neither are the soldiers on the Artemision at Magnesia. Some 15 per cent of the soldiers on this latter monument are wearing high boots, but it is likely that they are dismounted cavalry. The frieze at Pergamum dating from the early second century shows just one pair of greaves which have two straps, one below the knee and one near the ankle (Jaeckel 1965, fig. 40). With the possible exception of the Macedonian phalanx of Philip V (and the new Achaean, sarissa-armed phalanx of c. 200), the evidence does seem to show that greaves were restricted to officers throughout the Hellenistic period. Since armour was then provided by the state, greaves were seen perhaps as too expensive a luxury for everyone to have. There is no certain evidence for greaves ever having been worn by the cavalry, who wore the high boot as recommended by Xenophon.

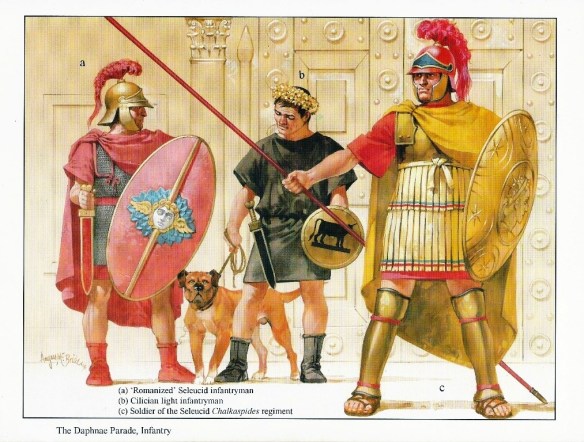

LIGHT INFANTRY

Nearly all the light infantry who fought for the Hellenistic kingdoms were mercenaries, although under Alexander some may have been allied contingents, like his Cretan archers. At Raphia 5,000 Greeks fought for Antiochus III and they were probably peltasts, since they fought with the other light troops. After the Celtic invasion of Greece and the subsequent removal of some Celts (the Galatians) to Asia Minor in the 270s, Greek light troops seem to have stopped using the pelta, and adopted instead the large, oval Celtic shield with a central spine. This shield was called in Greek the thureos, and so the soldiers are often called thureophoroi. Mercenary Greeks armed with this shield, and javelins or spears, also fought at Magnesia in 190. Some parts of Greece, especially in the North Peloponnese, had never adopted hoplite warfare because of the terrain; they always fought as peltasts and, later, as thureophoroi. Plutarch tells us that the Achaeans fought like this until shortly before 200, when they decided to adopt the sarissa, helmets, greaves, the Macedonian shield and Macedonian tactics (Plutarch, Philopoemen 9.1–5).

We are fortunate to have a surviving thureos from late second-century Egypt. Although both Connolly (1998, p. 131) and Sekunda (2001, pp. 81–2) suggest that this shield is Roman, and the excavator thought it was Celtic (belonging to a Celtic mercenary), there really is no problem, since both Roman shield and thureos were derived from the Celtic long shield. The Egyptian example cannot be Roman, as Romans did not reach Egypt for another 100 years. Sekunda’s explanation is that late Ptolemaic (and Seleucid) armies adopted Roman equipment. This will be discussed later. The thureos from Egypt is about halfway between a rectangle and an oval, and is 128cm high and 63.5cm wide with a slight concavity. It is made up of three layers of wooden laths each 2–3mm thick, constructed in a form similar to plywood for extra strength. It has a central handgrip, protected by a boss with a long vertical spine, and the outside was originally covered with felt. It would have given much greater protection to light troops than the smaller pelta did, especially now that missile weapons were far more common on the battlefield. There is little evidence about whether these thureophoroi wore helmets or not. It is probably a case of yes, if they bought them themselves or picked them up after a battle. They were probably not issued with them. They certainly seem to have worn no other body armour.

Northern Greece also provided javelineers and slingers called Agrianians (Polybius V, 79, 6). These men may have continued to use the small pelta shield, and there is an example from Olympia of a small ‘Macedonian’ shield, only 33.8cm in diameter, which could have been used by such troops (Liampi 1998, p. 51, plate 1.1). At the Battle of Raphia in 217 Antiochus III had 5,000 light troops, 2,000 Agrianian and Persian archers and slingers, and 2,000 Thracians. Thracians armed with the rhomphaia, a large, single-edged cutting weapon (Webber 2001, p. 39), were used by Perseus at the Battle of Pydna in 168 (Plutarch, Aemilius Paullus XVIII, 3) and a novel weapon, also used in this war by Perseus, was the cestrus. This was rather like a catapult bolt, or large arrow, but was fired from a special type of sling (Polybius XXVII, 1; Livy XLII, 65, 9).

As mentioned above, Agrianian archers featured at the Battle of Raphia in 217, but most archers continued to be supplied by Crete. Both Cretans and Neo-Cretans fought at Raphia. Neo-Cretans were probably ‘newly armed’ Cretans, rather than ‘newly recruited’ or ‘newly arrived’ (Griffith 1935, p. 144), and so it may have been at this time, rather than under Alexander, that Cretan archers were armed with a small shield and sword for close combat (Sekunda 1984, pp. 35–6). Antiochus III also had 2,500 Mysian archers at Raphia, and in general the Seleucids had much greater access to native missile and other light troops from their cosmopolitan empire.

Cavalry played a much more important part in Greek warfare in the fourth century and later. Philip II and Alexander the Great used large squadrons of heavy cavalry to break the enemy line while the phalanx held them up. In the later Hellenistic kingdoms the infantry had more of a role in both Macedonia and Ptolemaic Egypt. This was because Macedonia had not the funds any more to equip a large force, whereas Egypt did not have the breeding grounds. Only in the Seleucid Empire, and later the empire of Pergamum, did cavalry form a high percentage of the army as a whole.

Nearly all this cavalry fought with the spear, but there was a unit of cavalry under Alexander called sarissophoroi, who obviously used the sarissa as an offensive weapon. This cannot possibly have been the infantry sarissa of 18ft in length, because that would have required two hands to wield it, which was not an option in a period before decent saddles had been devised. Connolly (2000, pp. 107–9) has reconstructed a cavalry sarissa 16ft long, weighing just over 3.5kg, which in trials was successfully used both underarm and overarm with one hand. There are no later mentions of sarissophoroi, and it is likely that all later Hellenistic cavalry used the xyston, a spear about 9ft long. As a sidearm, the cavalryman used the single-edged, recurved sword, the machaira or kopis. This was recommended by Xenophon for cavalry use, and several surviving examples – generally the longer ones – have horse-head handles implying cavalry use. Cleitus cut off the arm of Spithridates the Persian at the Battle of the Granicus with his machaira, during a cavalry engagement (Arrian 1.15.8), and all the wounds received by Alexander in cavalry fights were caused by swords. It seems likely that the cavalry spear often broke following the initial charge, and so the sword was certainly a vital second weapon to have.

CAVALRY: SHIELDS AND ARMOUR

Cavalry played a much more important part in Greek warfare after 400. We have already noted the amount of armour recommended by Xenophon for cavalry use, and heavily armoured cavalry became the new force in warfare, in addition to the light cavalry that was still used. Philip II of Macedon had a force of 3,000 Macedonian and allied Thessalian cavalry when he conquered the rest of Greece, and Alexander took 5,100 horse to conquer Persia. The early battles of the Successors in the late fourth century feature anything from 6,000 to 11,000 cavalry per side. While 5,000–6,000 is the norm through most of the third century (at least where we have any information about numbers), Antiochus III was able to raise a large force of over 12,000 for the Battle of Magnesia in 190. Much of this was due to the consolidating campaigns Antiochus had carried out in the east of his empire. These enabled him to field 1,200 Dahae mounted archers and other native troops, as well as to afford Galatian mercenaries and call in other allies. While light cavalry was used for scouting and skirmishing, the armoured cavalry was used for attack, especially on the flank of the opposing phalanx. The men of this heavy cavalry wore helmets and cuirasses, and used the spear.

It is almost certain that the cavalrymen of Alexander did not carry shields, despite occasional references to them by later authors who are confusing them with later Hellenistic cavalry (Plutarch, Alexander of Macedon XVI, 4). Cavalry shields are not shown on the Alexander mosaic or on the Alexander Sarcophagus, as the rider needed his left hand to hold the reins and also to help him to stay on the horse – not easy with a primitive saddle and no stirrups. Cavalry shields first appeared with the arrival of the Celts in Greece and Asia Minor in 275. Celtic horsemen carried their round shields with a central handgrip, and must have controlled their horses entirely by leg movements. They could have taught Greek cavalrymen to do the same, and they probably also introduced the much more effective Celtic saddle, which had pommels at the four corners to help keep the rider on his mount (Connolly 1998, p. 236). Greek cavalry then adopted the round Celtic shield, but seem to have added a Greek grip with a central armband and a handle at the rim, and made the shield slightly concave rather than flat (Jaeckel 1965, figs 44–7). One example on the Pergamum frieze has the barleycorn boss, like the thureos from Egypt; this may have been a Celtic (Galatian) shield, since this monument shows arms of Antiochus III’s Galatian allies as well as Greek equipment. A Macedonian cavalryman on the Aemilius Paullus monument also has this type of shield boss, however, and so it is clear that the Greeks used Celtic shields, as well as those of their own design (Coussin 1932, plate 40; Liampi 1998, fig. 11.3).

Macedonian cavalry-shield designs were similar to the infantry, consisting of geometric circle and half-circle patterns (Head 1982, p. 113). These feature on both the Pergamum frieze and the Aemilius Paullus monument, and appear to be about 70 to 75cm in diameter (Liampi 1998, pp. 53–6 and fig. 11.1).

The various helmets available to the cavalry have been mentioned in the infantry section. No helmets seem to have been specific for one branch or the other, but the monuments we have been discussing seem to suggest that Hellenistic cavalry preferred open-faced helmets like the Boeotian and Cone helmets. Similarly, all the body-armour types have been mentioned in the section dealing with infantry. The information put forward there, and the use to which heavy cavalry was put, strongly suggest that they were armoured with metal breastplates. Cavalrymen were generally drawn from the wealthier aristocracy (men who could ride!) and so were able to provide themselves with equipment to supplement any provided by the state. It is significant that the latest muscle cuirasses from south Italy, and the example from Prodromi, are all made so that the wearer could ride a horse – either by being made with a wide flange at the bottom or by being short and ending at the waist (Connolly 1998, p. 56).

Apart from the muscle cuirass, shoulder-piece corslets made of metal – like that from the tomb of Philip II – also seem to have been worn, most notably by Alexander on the Alexander mosaic. However, it is also true that some of Alexander’s cavalry made do with linen corslets, as he did himself at the Battle of Gaugamela, although this was a Persian corslet and was perhaps worn for that reason. As noted above, greaves seem never to have been worn by cavalry. They would have interfered too much with the horseman’s grip, especially once the shield had been adopted. Other pieces of body armour seem to have been used only by cataphract cavalry and perhaps chariot drivers, and will be discussed below; the only notable exception is a throat guard that Alexander also wore at Gaugamela.