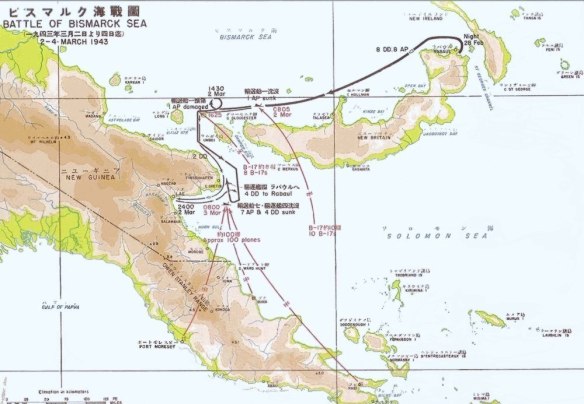

Japanese ship and Allied air movements during the battle.

Japanese movements in eastern New Guinea, 1942-1944.

A B-24’s chance discovery of a sixteen-ship Japanese convoy on March 1, 1943, set off a three-day running battle (March 3–5) between Japanese and Allied forces in the Bismarck Sea. On the one hand was a very determined Japanese convoy escort of eight destroyers commanded by Rear Admiral Masatomi Kimura, who intended to deliver the 51st Imperial Infantry Division and over thirty thousand tons of critical fuel, ammunition, and other supplies to the beleaguered Japanese forces in New Guinea. He was supported by Admiral Kusaka’s Eleventh Naval Air Fleet. Their opponents were General Kenney with his Fifth Air Force and a small squadron of PT boats. Coming at a crucial point in the New Guinea campaign, the outcome in the Bismarck Sea would have a direct and decisive effect on the campaign ashore.

The convoy run had been ordered by the Japanese commanders in Rabaul. General Okabe’s failure to seize the port of Wau had jeopardized Japan’s overland campaign to capture Port Moresby. Logistics were the key. Both Japanese and Allied forces were at the end of their logistical tether. Japanese army and naval air squadrons desperately needed fuel and spare parts, while the ground forces needed food, ammunition, and fresh troops. The convoy’s merchant ships and oilers would deliver the required material, while two troop transports would carry the 51st Division; its nearly seven thousand troops could tip the balance ashore. Recognizing the Allied air threat, Admiral Kusaka ordered daily combat air patrols and provided eight destroyers with strong antiaircraft batteries to protect the convoy. Admiral Kimura also expected to encounter U.S. submarines, but he could do little except order additional lookouts. Few of his destroyers had active sonar, but it was their lack of radar and air cover which would prove decisive in the coming battle. The submarine threat never materialized.

The convoy departed Rabaul on February 28 and was detected late in the afternoon of the next day. A rainstorm hindered Allied efforts to shadow the convoy, and it was lost at sundown, before any air strikes could be launched. It was rediscovered the next morning, and seven B-17s forged through the bad weather to press home their attacks. Three attacked from high altitude and missed, but four struck from below 6,000 feet, sinking one transport and damaging two others. Later attacks were less successful, their efforts hampered by bad weather, aggressive Japanese fighter patrols, and the bombers’ limited numbers. Sunset brought the Japanese a reprieve, but the next day would see both sides redouble their efforts. Two destroyers picked up survivors and delivered them to Lae overnight, returning to rejoin the convoy in the early morning.

General Kenney ordered a maximum effort for the next day, including all available Australian as well as U.S. aircraft. The resulting 137 bombers with supporting fighter escorts overwhelmed the forty-two Japanese naval Zeros protecting the convoy. Lacking radar to vector their fighters to the bombers, the Zeros became embroiled with the Allied fighter escorts while the heavy and medium bombers punched through unscathed to strike the convoy. The American A-20s and B-25s employed the new “skip-bombing” technique and recently installed forward firing armaments to devastating effect. Every ship suffered some damage— several, seriously.

Two destroyers, including flagship Shirayuki, and a transport were sunk. Another destroyer and three merchant ships were knocked dead in the water. Several ships were burning. The next wave of Allied aircraft nearly finished the convoy off, critically damaging one destroyer and sinking the previously crippled destroyer and two more cargo ships. The surviving transports were immobilized, and the water was littered with struggling seamen and soldiers. The Japanese sent dozens of fighters to provide air cover and despatched two submarines to pick up survivors. Two destroyers fled to Rabaul packed with 2,700 survivors. Two others, Yukikaze and Asaguma, remained behind to pick up the remainder and fled during the night. The one surviving crippled cargo vessel, Oigawa Maru, and the two remaining disabled destroyers were finished off by American PT boats that night and by American bombers the next morning, respectively. Another transport went down that night. The Japanese submarines I-17 and I-26 marked the last moments of the battle by fishing more than two hundred survivors from the water during the evening of March 4. American PT boats unsuccessfully attacked the latter submarine as it was finishing its mission. The Battle of the Bismarck Sea, a disaster for the Japanese, was over.

The Japanese lost more than four thousand men and nearly thirty thousand tons of supplies in the battle. This devastating defeat ended Japan’s strong efforts to reinforce its forces on New Guinea. The combination of deadly Allied air power by day and PT boat patrols by night all but strangled the Japanese forces in New Guinea. All future Japanese logistics support would come by submarine and would never approach the quantities needed to support effective ground operations. In effect, the Allied victory in the Battle of the Bismarck Sea both demonstrated air power’s dominance in naval warfare and also ensured the ultimate Allied victory ashore.

#

The Bismarck Sea was the debut of the B-25 strafer and Bristol Beaufighter. Both had been in action previously, but never with such effect. Fred Cassidy was aboard a Beaufighter at the Bismarck Sea:

When attacking ships we liked to come in from the front. It was our goal to put the bridge out of order. You would begin the approach sideways, maybe three-quarter speed, perhaps 220 knots, and about four miles off. Then we’d run parallel. We’d make a big wide turn, get into line astern, usually a flight of maybe three. We’d start at the back of the ship and make a big sweeping turn and come in from the front and begin the dive from about 500 feet. The ship would be about 600 yards in front. You’d let go with your cannon at maybe 100 yards from the ship, aim straight at the bridge, and turn straight off. You’d pull up over the mast. You’d watch the ship kind of disintegrate. In the Bismarck Sea battle we strafed from the front. The ships were careening in all directions. I saw a 500-pound bomb level with our starboard wing going at the same altitude and same speed that we were that a Mitchell had just dropped, maybe twenty feet off the water. You also had to dodge bomb-splashes at the Bismarck Sea because the Liberators and ’17s were dropping from 6,000-10,000 feet and they’d make huge splashes when we were about twenty feet off the sea. These splashes were thirty to fifty feet across and followed by a tremendous spout of water. We had to fly through those. The damage done to the Japanese was devastating.

Veteran B-25 pilot Garrett Middlebrook had an unusually close ringside seat to the Bismarck Sea debacle:

After the Bismarck Sea we converted to eight .5O-calibers in the nose, which were awesome, absolutely awesome. It was absolutely unreal what they could do. I saw it often, first at the Bismarck Sea. This was a very interesting mission for me-it was the only one I flew as a copilot of the sixty-five I flew during the war. Midway through the mission I thought I was fortunate. The pilot was doing all the work and I was a witness to history being made-we knew this was a big show that would live in the history books for 100 years. During the battle we circled out there waiting our turn to go in, a good mile away. The A-20s went in first, and then the strafers of 30th Bomb Group arrived. They went in and hit this troop ship. What I saw looked like little sticks, maybe a foot long or something like that, or splinters flying up off the deck of the ship; they’d fly all around . . . and twist crazily in the air and fall out in the water. I thought, “What could that be? They must have some peculiar cargo on that vessel.” Then I realized what I was watching were human beings. It was a troopship just loaded. When the third group hit them two of the ships went in and unloaded with those sixteen machine guns and most likely the turret gunner upstairs was having a little fun, too. I was watching hundreds of those Japanese just blown off the deck by those machine guns. They just splintered around the air like sticks in a whirlwind and they’d fall in the water. Soon afterwards we attacked a destroyer that was fleeing. We didn’t have the nose guns but hit him square with two bombs at mast level.

After the war former Rabaul staff officer Masatake Okumiya described the anguish caused by the Bismarck Sea among Japanese leaders:

The effectiveness of enemy air strength was brought to [Admiral Yamamoto] with the news of a crushing defeat which, if similar events were permitted to occur in the future, promised terrifying disasters for Japan. . . . Our losses for this single battle [Bismarck Sea-EB] were fantastic. Not during the entire savage fighting at Guadalcanal did we suffer a single comparable blow. It became imperative that we block the continued enemy air activities before these attacks became commonplace. We knew we could no longer run cargo ships or even fast destroyer transports to any front on the north coast of New Guinea, east of Wewak. Our supply operation to north-eastern New Guinea became a scrabbler’s run of barges, small craft and submarines.

After the Bismarck Sea the Japanese had to send convoys much farther up the coast out of air attack range, for the moment causing immense difficulties in getting them to the front. Yet troops sent forth were hardly safe. After the war Japanese officers at Rabaul estimated that 20,000 troops were lost during sea transit in the Rabaul-New Guinea area. As the months went on U.S. submarines operating in Southeast Asian waters and off Truk began to take their grim toll in addition to ships and barges destroyed by aircraft.

FURTHER READINGS Hoyt, Edwin P. The Jungles of New Guinea (1989). Morison, Samuel Eliot. History of United States Naval Operations in World War II, vol. VI (1968). Salmaggi, Cesare, and Alfredo Pallavisini. 2194 Days of War (1977).