Date January 30, 1789

Location Hanoi in northern Vietnam

Opponents (* winner)

*Vietnamese

Chinese

Commander

*Vietnamese Emperor Quang Trung (Nguyen Hue)

Chinese Sun Shiyi

Approx. # Troops

*Vietnamese Unknown

Chinese Unknown

Importance One of the greatest victories in Vietnamese history, it expels the Chinese from Vietnam

The Battle of Hanoi (Ngoc Hoi–Dong Da) of January 30, 1789, was fought between Vietnamese nationalists and the Chinese. Marking the end of the 1771–1789 Tay Son Rebellion, it is regarded as one of the greatest military victories in Vietnamese history. What might be called the First Tet Offensive, the Vietnamese offensive in 1789 was proof that this holiday was not always peacefully observed by warring Vietnamese and should have served as ample warning to the Americans and South Vietnamese authorities that the communist forces might strike during Tet in 1968.

In a brilliant campaign fought between May and July 1786, Nguyen Hue, the military genius of the three Tay Son brothers, defeated the Trinh lords in northern Vietnam and brought Emperor Le Chieu Thong under his control. After his victory Nguyen Hue returned to consolidate his authority in the south. Nguyen Hue’s lieutenant in the north turned traitor, however, and in collusion with the emperor attempted to fortify the region against Nguyen Hue’s return. Before Nguyen Hue could arrive with his army, Emperor Le Chieu Thong lost his nerve and fled to China. Once again, Nguyen Hue returned to the south.

Le Chieu Thong knew that the only hope of reclaiming his throne was Chinese assistance. Sun Shiyi, the Qing governor of territory bordering Vietnam, saw military intervention as an opportunity to assert Chinese influence in an area weakened by civil war. The Qing emperor agreed, and in November 1788 Sun Shiyi, assisted by General Xu Shiheng, led an expeditionary force of up to 200,000 men in an invasion of northern Vietnam. Faced with overwhelming Chinese strength, Nguyen Hue’s generals sent ships with provisions south to Thanh Hoa while the troops retired overland.

The Qing forces took the capital of Hanoi in late December 1788 after a campaign of less than two months, but events worked to undermine their authority. The Chinese treated Vietnam as captured territory and forced Le Chieu Thong to issue pronouncements in the name of the Chinese emperor. Many Vietnamese resented reprisals against imperial officials who had earlier rallied to the Tay Son. Typhoons and disastrous harvests also led many northerners to believe that the emperor had lost the Mandate of Heaven.

On December 22, 1788, after learning of the Chinese invasion, Nguyen Hue proclaimed himself emperor of Vietnam with the throne name of Quang Trung. He then raised an army. To widen his appeal, he played to Vietnamese nationalism, stressing the long history of Chinese efforts to subjugate Vietnam. The key to his military success was careful planning. In the course of a 40-day campaign, Quang Trung devoted 35 days to preparations and only 5 to battle.

Quang Trung first ordered his soldiers to celebrate the Tet holiday early. He then sent a delegation to Sun Shiyi with a request that the Qing withdraw from Vietnam. Sun tore up the appeal and put the chief of the delegation to death, boasting that he would soon take Quang Trung.

Quang Trung ordered the main military effort to be made against the principal Qing line, where he concentrated his elite troops and the elephants that transported his heavy artillery. At the same time, he sent a part of his fleet north as a feint against the capital to prevent the Chinese from concentrating their reserves on the main front. His plan to attack on the eve of Tet was a brilliant stroke, catching the Chinese off guard celebrating the lunar new year. Quang Trung also profited from Chinese errors. Confident in his superior numbers, Sun Shiyi relaxed discipline.

Quang Trung’s offensive, once launched, went forward both day and night (especially the latter) for five days. Each attack was mounted rapidly to prevent the Qing from bringing up reserves. Tay Son forces covered nearly 50 miles and took six forts defending access to the capital, a rate of 10 miles and more than one fort a day. The attackers were motivated by a desire to free their country from foreign domination. Indeed, tens of thousands of civilians joined the Tay Son army as it moved north.

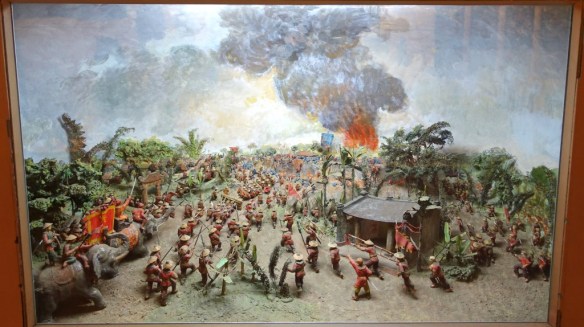

At dawn on the fifth day of Tet (January 30, 1789), Tay Son forces approached the fort of Ngoc Hoi, at Dong Da in the southern part of Hanoi, and came under heavy enemy fire. Elite commandos assaulted the fortress in groups of 20, protected under wooden shields covered by straw soaked in water. Quang Trung exhorted his troops from atop an elephant. Following intense fighting, the Tay Son emerged victorious; large numbers of Chinese, including general officers, died in the attack.

Sun Shiyi learned of the disaster that same night. With fires clearly visible in the distance, he fled north across the Red River, not bothering to put on his armor or saddle his horse. Qing horsemen and infantry soon joined the flight, but the bridge they used was overburdened and collapsed. According to Vietnamese accounts thousands drowned, and the Red River was filled with bodies. Le Chieu Thong also fled and found refuge in China, ending the 300-year-old Le dynasty.

True to his word, on the afternoon of the seventh day of the new year Quang Trung entered Hanoi. His generals continued to pursue the Chinese to the frontier. Mobility and concentration of force, rather than numbers, were the keys to the Tay Son victory. Quang Trung’s triumph is still celebrated in Vietnam as one of the nation’s greatest military achievements. The Vietnamese celebrate the Ngoc Hoi– Dong Da victory every year by a festival in Hanoi on the fifth day of the first lunar month.

Quang Trung became one of Vietnam’s greatest kings. Unfortunately, his reign was short. He died in the spring of 1792, so he did not have the “dozen years” that he believed were necessary to build a strong kingdom. His son was only six years old in 1792, and Quang Trung’s brothers also died in the early 1790s. Within a decade, the surviving Nguyen lord, Nguyen Anh, had come to power, and the Nguyen dynasty was dominant throughout Vietnam.

References Buttinger, Joseph. The Smaller Dragon: A Political History of Vietnam. London: Atlantic, 1958. Déveria, G. Histoire des Relations de la Chine avec L’Annam-Vietnam du XVIe au XIXe Siècle. Paris: Ernest Leroux, 1880. Le Thanh Khoi. Histoire de Viet Nam des origines à 1858. Paris: Sudestasie, 1981. Truong Buu Lam. Resistance, Rebellion, and Revolution: Popular Movements in Vietnamese History. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 1984. Viet Chung. “Recent Findings on the Tay Son Insurgency.” Vietnamese Studies 81 (1985): 30–62.