Above all his various warrior groupings, Chinggis created an elite force originally formed from his most loyal and longest serving companions. This bodyguard, whose size reflected the Great Khan’s prestige and power rather than any imminent danger to his life, numbered 10,000 men at the time of the 1206 quriltai. The keshig, or imperial guard, were recruited from across all tribal barriers, and the unit’s tasks multiplied as it increased in size. Membership in the keshig was regarded as a supreme honor, and as such, enlistment in its ranks was an alternative to the necessity of hostage taking for the highborn. The powerful nobility would be honored rather than shamed by the presence of their offspring in the imperial household. In addition, service in the royal household constituted military and administrative training. The keshig formed the breeding ground for the new elite and the future ruling classes. The children of any potential rival or source of conflict could therefore serve honorably at court and be painlessly co-opted into the ruling establishment.

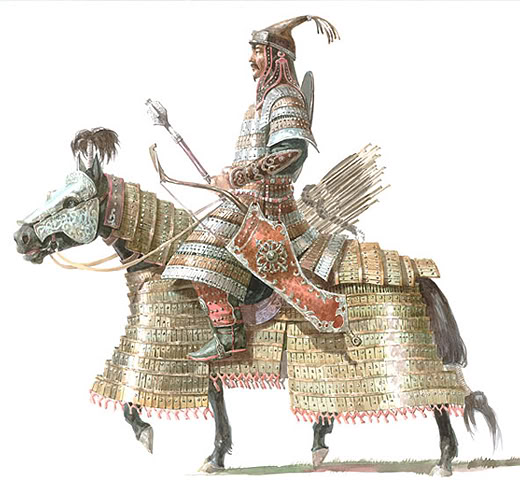

The keshig were handsomely equipped and armed. An ordinary soldier in the imperial guard had precedence over a commander in the rest of the army. It was from this unit’s ranks that the future generals and top commanders were selected. It was early recognized as a military academy as well as an administrative training school.

The training of the rest of the army was the responsibility of its officers. Officers were expected to inspect their troops regularly while on active service and to ensure that they were all fully equipped. This extended to such details as ensuring that each soldier had his own needle and thread, and if it were found that a soldier was underequipped or lacking in any item of clothing, armor, or weaponry, his commanding officer was deemed responsible and would be liable for punishment. During military engagement if any soldier lost or dropped any item of his personal gear or equipment, the man behind him would have to retrieve and return the lost item to its owner or suffer punishment, which could mean death. Death was also meted out to anyone who fled before the order to retire had been issued, anyone looting before permission had been granted, and for desertion. Discipline was exceptionally strict in the Mongol army.