By the tenth century the Pechenegs were dominating the steppe. Rus relations with them were complex. On the one hand, trade relations developed between these two peoples, whose economic activities complemented one another. The Rus found the horned cattle, horses, sheep, and other livestock raised by the nomads useful for food and clothing, for hauling and transport, and for a variety of secondary products such as leather goods. Horses were also particularly important as mounts for warriors. The grain raised by Slav agriculturalists, on the other hand, provided a desirable supplement to the Pecheneg diet of meat and dairy products. The mutual benefit to be derived from trade provided a basis for peaceful relations. From the early tenth century the Primary Chronicle presents an image of relatively tranquil relations between the two peoples; the Pechenegs even joined the Rus in 944 in a campaign against Byzantium.

Peaceful relations with the Pechenegs were important to the Rus not just for the opportunity to exchange their goods directly. They were also essential for the princes to conduct their trade with the Byzantines. Initially, the Norsemen had exchanged their booty at the Byzantine colony of Cherson. Rus offensives against Constantinople in 911 and 944 resulted in treaties that gave Rus merchants the right to trade in Constantinople as well, and also outlined their commercial rights and privileges. But to reach either Cherson or Constantinople the Rus had to cross the steppe controlled by the Pechenegs. Emperor Constantine recorded that after the Kievan prince made his rounds to collect tribute from the Slav tribes, he assembled a fleet of river boats, manufactured in Novgorod, Smolensk, Chernigov, and other towns, loaded his goods into them, and conducted this flotilla down the Dnieper River and along the western coast of the Black Sea to sell the products in Constantinople. Emperor Constantine emphasized that this practice depended upon peaceful relations between the Rus and the Pechenegs. Well aware of the potential dangers posed by the Pechenegs, who had on occasion attacked Cherson, he observed that these nomads had similarly raided Kievan Rus and were quite capable of inflicting considerable damage on it. He went on to note:

Nor can the Russians come at this imperial city [Constantinople] . . . either for war or for trade, unless they are at peace with the Pechenegs, because when the Russians come with their ships to the barrages [rapids] of the [Dnieper] river, and cannot pass through them unless they lift their ships off the river and carry them past by porting them on their shoulders, then the men of this nation of the Pechenegs set upon them, and, as they [the Rus] cannot do two things at once, they are easily routed and cut to pieces.

Shortly after the disintegration of Khazaria in the second half of the century, Rus–Pecheneg relations became more hostile. Pechenegs raided the frontier of Kievan Rus, seizing crops and captives who were then sold as slaves. They also, as Emperor Constantine had worried, attacked Rus commercial caravans descending the Dnieper or crossing the steppe on their way to and from Byzantine markets. In 968, Pechenegs attacked the Rusinterior for the first time and laid siege to Kiev. Vladimir’s father Sviatoslav, who had not been in Kiev at the time, was later killed during another encounter with the Pechenegs, who “made a cup out of his skull, overlaying it with gold, and . . . drank from it.”

The deterioration of Rus–Pecheneg relations became even more critical after Vladimir adopted Christianity. The consequent establishment of closer ties with Byzantium put a premium on the maintenance of security along the transportation routes that crossed the steppe and gave priority to a policy of neutralizing the Pechenegs, who were becoming more aggressive. In response, Prince Vladimir constructed a series of forts on the tributaries of the Dnieper, near and below Kiev, to guard the southern frontier; they were defended by Slovenes, Krivichi, and Chud transferred from the north. Almost immediately afterward, just as communication and interaction between Byzantium and Rus took on heightened importance, war broke out; it was highlighted by a series of Pecheneg attacks on Rus territory (992, 995, and 997). In one battle (996), which ended in a humiliating defeat, Vladimir personally avoided capture or death only by hiding under a bridge. Afterward, again relying on interregional cooperation, he collected another army in Novgorod and brought it south to continue the war, which persisted through the remainder of his reign. Just before his own death (1015), Vladimir sent his son Boris to lead a campaign against the Pechenegs; on his return Boris was killed by his brother Sviatopolk, who thereby launched a bloody succession struggle.

The net result of Vladimir’s defensive policies, however, was a success. The Pechenegs were driven deeper into the steppe away from Kievan Russettlements; the width of the “neutral zone” was doubled from the distance covered in one day’s travel to two. Pecheneg auxiliary forces, which began to be regarded as more effective than Varangian foot soldiers, participated in the war of succession fought by Vladimir’s sons after his death. But independent Pecheneg attacks on the Rus lands relaxed.

As a result of his foreign policies, Vladimir secured his borders as well as the trade routes running through his lands. He was thus able to sell the products he and his sons had collected as tribute from the Slav tribes to the Pechenegs and to merchants at Bulgar and Constantinople. At the other end point of the Rus trading network were the Scandinavian markets on the Baltic coast. The Rus retained close ties with their Scandinavian compatriots. Vladimir had sought refuge among them when he felt threatened by Iaropolk. He had been able to raise a Varangian force to assist him when he returned to overthrow his brother. Kievan Rus similarly offered sanctuary to exiled Scandinavians. One example of this reciprocal arrangement is reflected in the legend of the great Viking, Olaf Trygveson. After his father had been murdered, Olaf was trying to escape to the safety of Vladimir’s court, where his uncle held high rank; while en route, however, he was captured by pirates. In addition to exchanging exiled princes, the lands of Rus and Scandinavia also traded a variety of goods. By the time of Vladimir’s reign, silver coins, silks, glassware, and jewelry from Muslim and Byzantine lands as well as native Slav products were reaching Scandinavian market towns via the lands of Rus. Some of these items were brought back by Varangian mercenaries, who had been hired by the Rus princes. But much of it arrived as the result of commercial exchanges that took place, mainly at Novgorod, for a variety of European goods, including woolen cloth, pottery, and weapons.

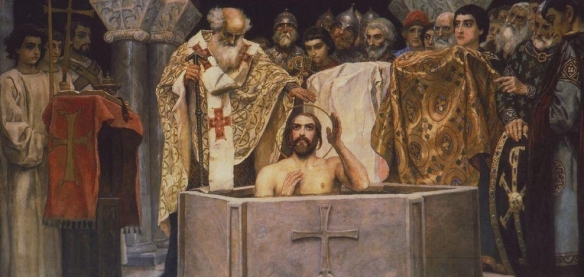

The achievements of Prince Vladimir, who died in 1015, were notable. He overcame competing Varangian dynasties (Polotsk) and thus secured the right of his dynasty to rule exclusively in the lands of the eastern Slavs, Kievan Rus. He also adopted Christianity for the peoples dwelling in those lands. He thus established the two enduring institutions, dynasty and Church, that would give definition not only to Kievan Rus, but also to its successor states.

Vladimir prevented rival neighboring states from encroaching on his realm, and he gained recognition and legitimacy for his dynasty from the powerful Byzantines and European Christian powers. With the latter he maintained generally cordial relations. The main exceptions had occurred early in his reign when he directed campaigns against the Poles for control of Cherven, located southwest of Kiev (981), and against the Lithuanian tribe of Iativigians on the Neman (Niemen) River to the northwest (983). After that, his relations with the central European states of Poland and Hungary as well as his Scandinavian neighbors were peaceful. They demonstrated their respect and acceptance of the Riurikids by intermarrying with Vladimir’s children. Sviatopolk married the daughter of King Boleslaw of Poland, while his half-brother Iaroslav wed the daughter of the Swedish king Olaf.

In conjunction with consolidating his personal and his dynasty’s position in Kievan Rus, Vladimir also successfully defended his realm from external aggression. He placed his sons with their retinues on the borders, he built forts to defend the southern frontier, and he forced the most aggressive foe of the Rus, the Pechenegs, to retreat. By the end of his reign transit across the steppe was safer and the Pecheneg threat to Kievan Rus was reduced. Vladimir’s administrative and defensive measures also enabled him and his sons to collect the revenue necessary to maintain the armed forces, required for both internal stability and external defense, and to continue commercial exchanges with the great empires of the region.

Vladimir’s policies accomplished more than the minimum necessary for his immediate political goals. The distribution of his sons around the country displaced tribal leaders and laid the groundwork for the formation of a political organization based on joint dynastic rule. The adoption of Christianity and dissemination of clerics who accompanied his sons focused the entire population of his country on a single set of religious principles, which also lent ideological support to his political authority, while the establishment of closer ties to Byzantium and simultaneous maintenance of trade relations with the Muslim East kept Kievan Rus open to a diverse array of cultural influences and material goods. The transfer of personnel from the north to man the southern forts protecting Kiev reflected an ability to mobilize resources from all over his lands for a single purpose and thereby encouraged a process of social integration. Vladimir’s policies thus laid the foundation for the transformation of his domain from a conglomeration of tribes, each of which separately paid tribute to him, into an integrated realm bound by a common religion and cultural ties as well as the political structure provided by a shared dynasty.