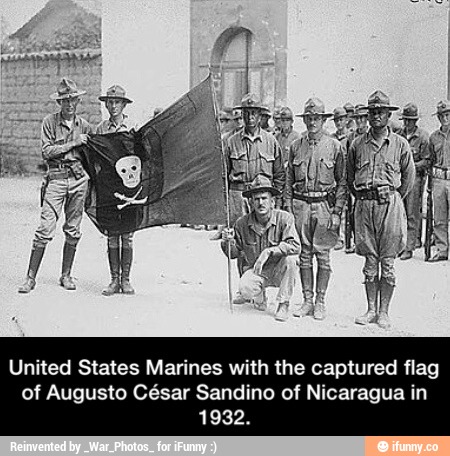

United States marines with the captured flag of Augusto César Sandino in 1932.

“Gunboat diplomacy” refers to a foreign policy that relies on force or the threat of force. To some extent, such an approach to foreign policy has always existed between empires and nations. But in the American political lexicon the term is most commonly applied to U.S. foreign policy in the Caribbean, Central America, and the northern tier of South America during the first three decades of the 20th century. Thereafter, this policy gave way to the “Good Neighbor Policy” formulated first by Herbert Hoover and then put into practice by Franklin D. Roosevelt, whereby the United States would commit to refraining from armed intervention in Latin America.

One of the first examples of American gunboat diplomacy was the mission of Comm. Matthew C. Perry, who steamed with eight ships, one-third of the U.S. Navy, to “open” Japan to trade with the United States in 1853. When Perry returned, as promised, the next year, the Tokugawa Shogunate agreed to the Treaty of Kanagawa in part out of recognition of what unbridled European powers were doing in nearby China. Naval shows-of-force followed in Korea, Hawaii, and China.

The Spanish–American War in 1898 gave the United States an overseas empire after the seizure of territories in the Caribbean and the Pacific. The war made clear the advantages of an ocean-going Navy to defend both coasts, the benefits of a trans-isthmian canal in Central America to save the long sea voyage around the southern tip of South America, and the need to secure bases in the Caribbean at the canal’s eastern approaches. This strategic interest, coupled with pressure from banks and other businesses in the region, prompted the State and Navy departments to commit naval and marine forces to the Caribbean and Central America after 1895. Between the war with Spain in 1898 and U.S. entry into World War I in 1917, the U.S. government established a virtual hegemony in these waters. Some in the United States, calling themselves anti-imperialists, expressed their opposition to such interventions.

The process was aided by Pres. Theodore Roosevelt’s corollary to the Monroe Doctrine. To prevent German interference in 1904 in the affairs of the Dominican Republic, he declared and assumed the right of “an international police power,” a right that he and succeeding presidents later exercised in Cuba, Nicaragua, Mexico, Haiti, and other nations. Roosevelt had already interfered in Colombian affairs. A French company had failed at great cost to construct a canal across the narrow Panamanian isthmus, which was at the time a part of the province of Panama in Columbia. An official in that company and some Panamanian elites conspired in 1903 to establish an “independent” Panama; Roosevelt quickly recognized Panama as a sovereign nation and ordered U.S. naval forces to move toward the new country’s coasts to defend against a possible response from Columbia. The leaders of the newly independent Panama signed a treaty giving the United States rights to build and operate a canal and to control land on either side until 1999. The canal, completed in 1914, remains an engineering marvel. More important in terms of gunboat diplomacy, the Panama Canal also drew U.S. government attention to the affairs of the Caribbean and Central America.

U.S. Army troops returned to Cuba from 1906 to 1909 under terms of the Platt Amendment of 1901, which forbade outright annexation of the island. In 1909, the U.S. Marines helped overthrow the government of Nicaragua, and they virtually occupied that country from 1912 through 1933. The U.S. Marines largely ran the Dominican Republic from 1916 to 1924.

In succeeding years, U.S. armed forces regularly interfered in the domestic affairs of sovereign nations to the south. After chasing Pancho Villa in northern Mexico, American armed forces occupied the Mexican port of Veracruz from 1914 to 1916. The United States also occupied Haiti from 1915 to 1934.

The catchphrase used to justify such interference in the internal affairs of other countries changed over the decades. During the presidency of Theodore Roosevelt, it was the “Roosevelt Corollary”: if a Caribbean or Latin American nation failed in its obligations to a “great power,” the United States, invoking this Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine, would intervene in the offending nation and “correct” the “problem.” During the presidency of Howard Taft, it was “Dollar Diplomacy,” the aim of which was to secure the Caribbean and the bordering nations of Latin America for investment by U.S. banks and corporations by posting American Customs and Treasury officials in nations that were on the brink of bankruptcy. Pres. Woodrow Wilson wanted to expand Progressivism into foreign relations, and he justified the continuation of gunboat diplomacy by the need to punish “immoral” nations in the region. The Republican presidents of the l920s returned to Dollar Diplomacy and a hunt for stability. In the 1930s Pres. Franklin Roosevelt, despite a few brief landings of naval personnel in Cuba to protect American property, advanced the “Good Neighbor Policy,” which seemingly ended this era of American intervention in the affairs of other nations. Roosevelt proclaimed that “in the field of world policy I would dedicate this Nation to the policy of the good neighbor— the neighbor who resolutely respects himself and, because he does so, respects the rights of others.” Thus an era appeared to come to an end.

Depending on one’s perspective, however, the United States may be said to have continued Gunboat Diplomacy as a means of statecraft around the world. In the aftermath of World War II and the onset of the Cold War, U.S. military and the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) intervened, with mixed success, to prop up or to establish regimes friendly to the United States regardless of their democratic status. In 1953, the CIA helped overthrow the supposedly communist-leaning regime of Mohammed Mossadeq in Iran, restoring the shah to power. The following year, the United States overthrew Jacobo Arbenz Guzman in Guatemala. The U.S. government supported Cuban dictator Fulgencio Batista in Cuba until 1959 and thereafter tried to destabilize the government of Fidel Castro, including training and then inadequately supporting the invasion of Cuban exiles at the Bay of Pigs in 1961. Pres. Lyndon Johnson approved an occupation of the Dominican Republic in 1965 to overthrow Juan Bosch, and Pres. Richard Nixon supported the overthrow of the Allende regime in Chile. A Senate committee in the late 1960s discovered that the Navy had deployed carrier task groups throughout the world in reaction to reports of “trouble” some 62 times in the 15 years since the outbreak of the Korean War, and that the State Department had been aware of only 29 of these deployments.

Some critics claim that the United States has never abandoned gunboat diplomacy, using an expansive definition of the term whereby military action, short of total war, replaces diplomacy and blurs the line with “limited war.” Such critics would characterize the American war in Vietnam, the Persian Gulf War, and the subsequent Iraq War, which began in 2003, as modern examples of gunboat diplomacy. Others feel that the term should be limited to its original context.

Bibliography Andrew, Graham Yooll. Imperial Skirmishes: War and Gunboat Diplomacy in Latin America. Brooklyn, N.Y.: Olive Branch Press, 2002. Cable, James. Gunboat Diplomacy: Political Applications of Limited Naval Force. New York: Praeger, 1971. Hagan, Kenneth J. American Gunboat Diplomacy and the Old Navy, 1877–1889. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1973. Healy, David. Gunboat Diplomacy in the Wilson Era: The US Navy in Haiti, 1915–1916. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1976.

Further Reading Boot, Max. Savage Wars of Peace: Small Wars and the Rise of American Power. New York: Basic Books. 2002. Hyam, Ronald. Britain’s Imperial Century, 1815–1914: A Study of Empire and Expansion. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2002. Langley, Lester D. The Banana Wars: United States Intervention in the Caribbean, 1898–1934. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1985. Munro, Dana G. Intervention and Dollar Diplomacy in the Caribbean, 1900–1921. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1964. Wood, Bryce. The Making of the Good Neighbor Policy. New York: Columbia University Press, 1961.