The great distances of Poland and its relatively low density of population led to a greater emphasis on cavalry than in western Europe. The Poles had to confront opponents with very different tactics and did so with some success. Although Warsaw fell to the Swedes in August 1655 and to the Transylvanians in 1657, the Poles were able to regain the city, not least because of their invaders’ difficulties in controlling the countryside and supply routes.

EASTERN EUROPE was a major field of conflict in the seventeenth century as Austria, Poland, Russia, Sweden, and the Ottoman Empire all sought territorial advantage over their rivals. Russia continued to seek a Baltic coastline, while the Swedes sought to dominate the eastern Baltic. This conflict turned Poland into a battleground for much of the century.

THE IMPACT OF SWEDEN

Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden attacked Poland in 1617-18, 1621-22, and 1625-29, capturing the important Baltic port of Riga (1621) after a siege in which he used creeping barrages (systematically advancing artillery bombardment). He overran Livonia in 1625. These campaigns ensured that the Swedes were battle-hardened when Gustavus invaded Germany in 1630.

Encounters with the Swedes led both Poland and Russia to experiment with new military ideas. In 1632-33, the Poles created musketeer units, replacing the earlier arquebusiers, and attempted to standardize their expanding artillery. Imitating the Swedes, the Poles introduced 3- to 6-pounder (1.4-2.7kg) regimental guns between 1633 and 1650. The Russian government, conscious of Swedish developments and dissatisfied with the streltsy, the permanent infantry corps equipped with handguns founded in 1550, decided in 1630 to form ‘new order’ military units, officered mainly by foreigners. Ten such regiments, totalling about 17,000 men, amounted to half the Russian army in the War of Smolensk with Poland (1632-34).

However, these changes were not decisive. Smolensk had been well fortified by the Russians before being lost to Poland during the Time of Troubles (1604-13), caused by a disputed succession. The Russian Siege of Smolensk (1632-34) was unsuccessful, and the Polish army under Wladyslaw IV inflicted a heavy defeat, with the Russians losing all but 8,000 of their 35,000 men. At the end of the war, the new Russian units were demobilized and the foreign mercenaries ordered to leave. Despite improvements to the Polish army, their few thousand infantry, dragoons, and artillery proved inadequate against a renewed Swedish invasion by Charles X, who seized Warsaw and Cracow. After their defeats at Zarnow and Wojinicz in 1655, the Poles avoided battle with large Swedish formations, relying instead upon surprise attacks and raids.

POLISH TACTICAL ALTERNATIVES

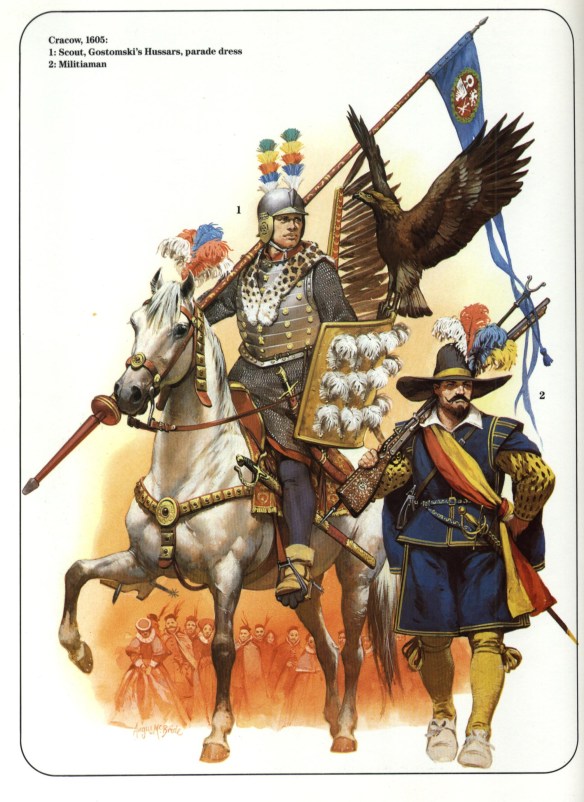

The Poles and Russians had not only to fight ‘western’ style armies like the Swedes, but to resist the still powerful Turks and their Tatar allies. The Poles won cavalry victories over the Swedes at Kokenhausen (1601), Kirchholm (1605), and over a much larger Russo-Swedish army at Klushino (1610), though at Klushino the firepower of the Polish infantry and artillery also played a major role. The mobility and power of the Polish cavalry, which relied on shock charges, nullified its opponents’ numerical superiority, and the Poles were able to destroy the Swedish cavalry before turning on their infantry. The Polish cavalry were deployed in shallower formations than hitherto. Just as the Dutch did not sweep to victory over Spain after the adoption of the Nassau reforms, so Gustavus was unable to defeat the Polish general Stanislaw Koniecpolski in his campaigns in Polish Prussia of 1626-29, where the two armies were roughly equal in quality. In view of the strength of the Polish cavalry, Gustavus was unwilling to meet the Poles in the open without the protection of fieldworks, while Polish cavalry attacks on supply lines and small units impeded Swedish operations. After defeating Christian IV of Denmark at Wolgast in September 1628, the Emperor Ferdinand II sent 12,000 men to the aid of his brother-in-law, Sigismund III of Poland, and the joint army advanced down the Vistula in 1629, pressing Gustavus hard at Honigfelde in June. In 1656, Stefan Czarniecki successfully used similar tactics of harassment, obliging the Swedes, who were not able to maintain their supplies, to withdraw: a Swedish force under Margrave Frederick of Baden was then destroyed by Polish cavalry at Warka, and Charles X was forced to abandon Warsaw and fell back on Polish Prussia. The Swedes had to admit failure.

Although the infantry techniques of countermarching and volley fire were not without relevance in eastern Europe, the small number of engagements fought between linear formations and settled by firepower is a reminder that these innovations were not all-powerful. Cavalry tactics remained especially important here, not least because the strategy of raiding could be employed to undermine an opponent’s logistics. Sieges also played only a relatively minor role, although control of bases such as Riga, Smolensk, and Danzig (Gdansk) was of great importance.