The year of 1812 had positively glowed with success for the Anglo-Portuguese forces in the Iberian Peninsula, but it ended inauspiciously, with the failure to take the castle of Burgos, besieged by the Marquis of (later the Duke of) Wellington in September and October. The Allied siege operations provided one of the more unhappy sides to Wellington’s campaign in the Peninsula, but at least the army was successful on three occasions (at Ciudad Rodrigo, Badajoz, and Salamanca), albeit after some tremendous bludgeoning, which cost the lives of thousands of British soldiers. At Burgos, however, the operation was flawed from the start, and a combination of bad weather, inadequate siege train, and plain mismanagement caused a despondent Wellington to abandon the dreary place on 19 October.

The outcome of the whole sad episode was a retreat that, to those who survived it, bore too many shades of the retreat to Corunna almost four years earlier. Once again the discipline of the army broke down, drunkenness was rife, and hundreds of Wellington’s men were left floundering in the mud to die or be taken prisoner by the French. It was little consolation to Wellington that while his army limped back to Portugal, Napoleon too was about to see his own army disintegrate in the Russian snows. The retreat to Portugal finally ended in late November when the Allied army concentrated on the border, close to Ciudad Rodrigo. The year had thus ended in bitter disappointment for Wellington, but nothing could alter the fact that taken as a whole 1812 had seen the army achieve some of its greatest successes, and once it had recovered it was to embark on the road to even greater success.

During the winter of 1812-1813, Wellington contemplated his strategy for the forthcoming campaign. His army received reinforcements, which brought it up to a strength of around 80,000 men, of whom 52,000 were British. The French believed that any Allied thrust would have to be made through central Spain, an assumption Wellington fostered by sending Lieutenant General Sir Rowland Hill, with 30,000 men and six brigades of cavalry, in the direction of Salamanca. Wellington, in fact, accompanied Hill as far as Salamanca to help deceive the French further. The main Allied advance, however, was to be made to the north, by the left wing of the army, some 66,000-strong, under Lieutenant General Sir Thomas Graham, who would cross the river Douro and march through northern Portugal and the Tras-o-Montes before swinging down behind the French defensive lines. The advance would be aimed at Burgos before moving on to the Pyrenees and finally into southern France. If all went well, Wellington would be able to shift his supply bases from Lisbon to the northern coast of Spain and in so doing, avoid overextending his lines of communication.

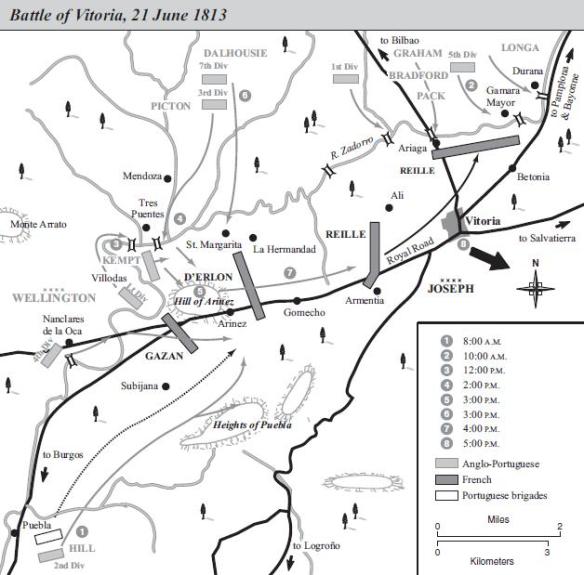

The advance began on 22 May 1813. Wellington left Hill’s force on the twenty-eighth and joined Graham the following day. By 3 June his entire force, numbering around 80,000 men, was on the northern side of the river Douro, much to the surprise of the French, who began to hurry north to meet them. Such was the speed of Wellington’s advance that the French were forced to abandon Burgos, this time without any resistance, and the place was blown up by the departing garrison on the thirteenth. Wellington passed the town and on the nineteenth was just a short distance to the east of Vitoria, which lay astride the great road to France. The battlefield of Vitoria lay along the floor of the valley of the river Zadorra, some 6 miles wide and 10 miles in length. The eastern end of this valley was open and led to Vitoria itself, while the other three sides of the valley consisted of mountains, although those to the west were heights rather than mountains. The Zadorra itself wound its way from the southwest corner of the valley to the north, where it ran along the foot of the mountains overlooking the northern side of the valley. The river was impassable to artillery but was crossed by four bridges to the west of the valley and four more to the north.

Wellington devised an elaborate plan of attack that involved dividing his army into four columns. On the right, Hill, with 20,000 men consisting of the 2nd Division and Major General Pablo Morillo’s Spaniards, was to gain the heights of Puebla on the south of the valley and force the Puebla pass. The two center columns were both under Wellington’s personal command. The right center column consisted of the Light and 4th Divisions, together with four brigades of cavalry, who were to advance through the village of Nanclares. The left center column consisted of the 3rd and 7th Divisions, which were to advance through the valley of the Bayas at the northwest corner of the battlefield and attack the northern flank and rear of the French position. The fourth column, under Graham, consisted of the 1st and 5th Divisions, General Francisco Longa’s Spaniards, and two Portuguese brigades. Graham was to march around the mountains to the north and by entering the valley at its northeastern corner, was to sever the main road to Bayonne.

King Joseph Bonaparte’s French army numbered 66,000 men with 138 guns, but although another French force under General Bertrand, baron Clausel was hurrying up from Pamplona, it did not arrive in time, and Joseph had to fight the battle with about 14,000 fewer men than Wellington.

On the morning of 21 June Wellington peered through his telescope and saw Joseph, Marshal Jean-Baptiste Jourdan, and General Honoré Théophile, comte Gazan and their staffs gathered together on top of the hill of Arinez, a round eminence that dominated the center of the French line. It was a moist, misty morning, and through the drizzle he saw, away to his right, Hill’s troops as they made their way through the Heights of Puebla. It was here that the battle opened at about 8:30 A. M., when Hill’s troops drove the French from their positions and took the heights.

Two hours later, away to the northeast, the crisp crackle of musketry signaled Graham’s emergence from the mountains, as his men swept down over the road to Bayonne, thus cutting off the main French escape route. Thereafter, Graham’s troops probed warily westward and met with stiff resistance, particularly at the village of Gamara Mayor. Moreover, Wellington’s instructions bade him proceed with caution, orders that Graham obeyed faithfully. Although his column engaged the French in several hours of bloody fighting on the north bank of the Zadorra, it was not until the collapse of the French army late in the day that he unleashed the full power of his force upon the French.

There was little fighting on the west of the battlefield until about noon, when, acting upon information from a Spanish peasant, Wellington ordered Major General James Kempt’s brigade of the Light Division to take the undefended bridge over the Zadorra at Tres Puentes. This was duly accomplished and brought Kempt to a position just below the hill of Arinez, and while the rest of the Light Division crossed the bridge of Villodas, Lieutenant General Sir Thomas Picton’s “Fighting” 3rd Division stormed across the bridge of Mendoza on their right. Picton was faced by two French divisions supported by artillery, but these guns were taken in flank by Kempt’s riflemen and were forced to retire having fired just a few salvoes. Picton’s men rushed on, and, supported by the Light Division and by Cole’s 4th Division, which had also crossed at Villodas, the 3rd Division rolled over the French troops on this flank like a juggernaut. A brigade of the 7th Division (Lieutenant General George Ramsay, ninth Earl of Dalhousie) joined them in their attack, and together they drove the French from the hill of Arinez. Soon afterward, what was once Joseph’s vantage point was being used by Wellington to direct the battle.

It was just after 3:00 P. M., and the 3rd, 7th, and Light Divisions were fighting hard to force the French from the village of Margarita. This small village marked the right flank of the first French line, and after heavy fighting the defenders were thrust from it in the face of overwhelming pressure from Picton’s division. To the south of the hill of Arinez, Gazan’s divisions were still holding firm and, supported by French artillery, were more than holding their own against Lieutenant General Sir Lowry Cole’s 4th Division. With Margarita gone, however, the right flank of the French was left unprotected.

It was a critical time for Joseph’s army. On its right, Jean-Baptiste Drouet, comte d’Erlon’s division was being steadily pushed back by Picton, Dalhousie, and Kempt, whose divisions seemed irresistible. Away to his left, Joseph saw Hill’s corps streaming from the heights of Puebla, while behind him Graham’s corps barred the road home. Only Gazan’s divisions held firm, but when Cole’s 4th Division struck at about 5:00 P. M., the backbone of the French army snapped. Wellington thrust the 4th Division into the gap between d’Erlon and Gazan, as a sort of wedge, and as the British troops on the French right began to push d’Erlon back, Gazan suddenly realized he was in danger of being cut off. At this point Joseph finally realized that he was left with little choice but to give the order for a general retreat.

The resulting disintegration of the French army was as sudden as it was spectacular. The collapse was astonishing, as every man, from Joseph downward, looked to his own safety. All arms and ammunition, equipment, and packs were thrown away by the French in an effort to hasten their flight. It was a case of every man for himself. Only General Honoré, comte Reille’s corps, which had been engaged with Graham’s forces, managed to maintain some sort of order, but even Reille’s men could not avoid being swept along with the tide of fugitives streaming back toward Vitoria. With the collapse of all resistance, Graham swept down upon what units remained in front of him, though there was little more to be done but round up prisoners, who were taken in their hundreds. The French abandoned the whole of their baggage train, as well as 415 caissons, 151 of their 153 guns, and 100 wagons. Two thousand prisoners were taken.

More incredible, however, was the fantastic amount of treasure abandoned by Joseph as he fled. The accumulated plunder he had acquired in Spain was abandoned to the eager clutches of the Allied soldiers, who could not believe what they found. Never before nor since in the history of warfare has such an immense amount of booty been captured by an opposing force. Ironically, this treasure probably saved what was left of Joseph’s army, for while Wellington’s men stopped to fill their pockets with gold, silver, jewels, and valuable coins, the French were making good their escape toward Pamplona. Such was Wellington’s disgust at the behavior of his men afterward that he was prompted to write to the Earl Bathurst, the secretary of state for war and the colonies. It was the letter in which he used the famous expression “scum of the earth” to describe his men.

The Allies suffered 5,100 casualties during the battle, while the French losses were put at around 8,000. The destruction of Joseph’s army is hardly reflected in this figure, however, and the repercussions of the defeat were far reaching. News of Wellington’s victory galvanized the Allies in northern Europe-still smarting after defeats at Lützen and Bautzen-into renewed action and even helped induce Austria to enter the war on the side of the Allies. In Britain, meanwhile, there were wild celebrations the length of the country, while Wellington himself was created field marshal. In Spain, Napoleon’s grip on the country was severely loosened, and there was now little but a few French-held fortresses between Wellington’s triumphant army and France.

References and further reading Esdaile, Charles J. 2003. The Peninsular War: A New History. London: Palgrave Macmillan. Fletcher, Ian. 1998. Vittoria 1813: Wellington Sweeps the French from Spain. Oxford: Osprey. Gates, David. 2001. The Spanish Ulcer: A History of the Peninsular War. New York: Da Capo. Glover, Michael. 1996. Wellington’s Peninsular Victories: The Battles of Busaco, Salamanca, Vitoria and the Nivelle. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson.—.2001. The Peninsular War, 1807-1814: A Concise Military History. London: Penguin. Napier, W. F. P. 1992. A History of the War in the Peninsula. 6 vols. London: Constable. (Orig. pub. 1828.) Oman, Charles. 2005. A History of the Peninsular War. 7 vols. London: Greenhill. (Orig. pub. 1902-1930.) Paget, Julian. 1992. Wellington’s Peninsular War: Battles and Battlefields. London: Cooper. Uffindell, Andrew. 2003. The National Army Museum Book of Wellington’s Armies: Britain’s Triumphant Campaigns in the Peninsula and at Waterloo, 1808-1815. London: Sedgwick and Jackson. Weller, Jac. 1992. Wellington in the Peninsula. London: Greenhill.