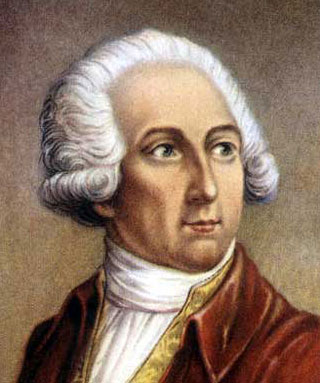

The longstanding connection between war and science in the West intensified during the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic era. Armed forces depended on scientific and technological expertise in many areas. Different service branches had different needs. One particularly marked by dependence on science was the artillery, since it was vital that guns be aimed correctly to inflict the most damage on enemy forces. Mathematics had only a limited impact on the actual practice of gunnery, which remained heavily influenced by rules of thumb and trial and error, but an appreciation of the value of applying mathematics to the science of gunnery did encourage armies to train their artillery officers in this discipline. Armies and navies also required scientifically educated men to satisfy the military need for gunpowder. The chemist Antoine-Laurent Lavoisier, a great scientific administrator, was the head of the French commission on powders in the old regime (1775-1783), meeting the needs of the American Revolutionary War and later the vastly greater conflicts of the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars.

The increasing professionalization of the officer corps of the European powers, and later of the United States, led to the integration of scientific training in military education, particularly for the artillery. Their common mathematical training helped form artillery officers into a cohesive body. This cohesion was particularly important in the French military, as the artillery officers held a socially inferior position with respect to cavalry and infantry officers. The ranking of students by their scores on mathematical exams helped form the artillery’s meritocratic culture, contrasting with other branches of the service where noble birth was more important.

Navies were also heavily dependent on science. In addition to the complex problems of firing guns effectively from ships rather than stationary platforms, navigation required a sophisticated knowledge of astronomy and mathematics. The world’s leading navy, Britain’s Royal Navy, required that its navigators be schooled in the method of lunar distances, which relied on careful observations of the moon to determine a ship’s longitude, a method developed in the eighteenth century. Cartography was also necessary to navies. The increasingly global wars of the eighteenth century had put a military premium on worldwide cartographic and hydrographic knowledge. Efforts to form a more complete and exact knowledge of the world’s seas and coasts were frequently and increasingly linked with navies. Captain James Cook’s voyages earlier in the century had begun a tighter, although not totally harmonious, relationship between British exploration and the Admiralty, one that became even closer during the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars. The leading hydrographer in late eighteenth-century Britain, Alexander Dalrymple, left his post at a private trading concern, the East India Company, to become the hydrographer to the Admiralty when the post was founded in 1795.

The Pacific was the most active site of oceanic exploration, particularly as expeditions were driven by imperial competition between Britain, France, the Netherlands, Spain, and Russia. The most active nations in Pacific exploration before the French Revolution were France and Britain. The Royal Navy expelled their French rivals from the high seas during the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars and continued Pacific exploration, sending George Vancouver to map the northwestern coast of North America from 1790 to 1795 and Matthew Flinders in the Investigator to circumnavigate Australia and examine its natural history from 1801 to 1805. Spain had lagged behind Britain and France, but by the late eighteenth century was attempting both to catch up scientifically and to assert its power over its North American colonies with a mission under the naval officer Alejandro Malaspina, which surveyed the Pacific coast of North America up to Nootka Sound in 1792. Continental exploration, such as America’s Lewis and Clark Expedition of 1804 to 1806, also had military implications and drew on military talent.

#

France was the largest state in Europe, in size and population, and throughout most of the century possessed the largest industrial output. The French state was dedicated to supporting economic growth in trade and industry, and was not afraid to use its large army to protect economic interests. The French did not lack in state protection, but they were far behind the revolutionary changes that had propelled Dutch and British success. France did not have the equivalent of Enclosure Acts, and the average French farm was very small, and so less suited to commercial agriculture. Despite the burdens of the feudal system, they were understandably reluctant to leave them and pursue opportunities in other sectors. They had also failed to revolutionize their tax system while still engaging in costly wars. State action was hindered by mounting debt and political unrest, which ultimately led to a complete change in government. The Revolutionary government changed the structure of land ownership, favoring small producers even more than before, but constant food shortages contributed to rampant inflation, which the government found itself relatively powerless to address. For the eighteenth century as a whole, it might be said that the Dutch had a financial revolution, the British had an industrial revolution, and the French had a political revolution.